"Writing like yourself or representing yourself on the page is also liberating" | Book Launch of How We Live Now

Livestream of How We Live Now Book Launch

The book launch of How We Live Now was livestreamed on the Ethos Books Facebook page on 19 June 2022. You can watch the livestream above and access the full transcript of the programme on this page. Portions of the transcript have been edited for clarity.

--

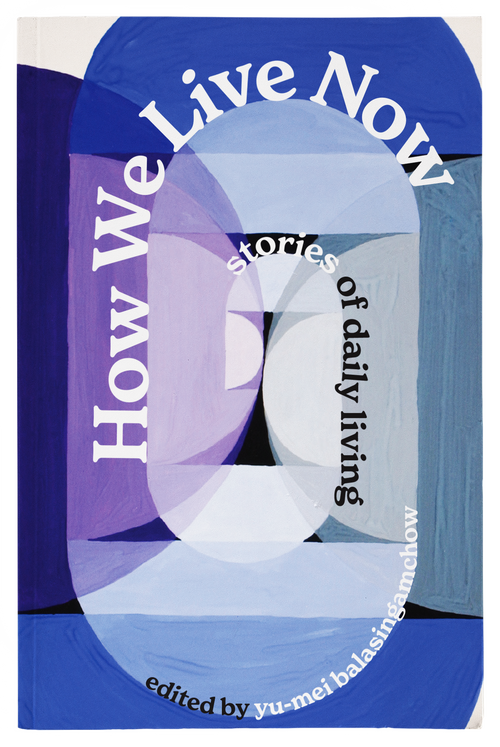

About How We Live Now: stories of daily living

How We Live Now offers a multi-faceted, multi-voiced view of contemporary life in Singapore: its comforts and conflicts, personal tragedies and social tensions, and also opportunities for joy, hope and empathy.

Featuring an exciting ensemble of both established and new writers, the stories invite readers to think seriously about the world around them, with urgent contemporary challenges such as social inequality and mental health, as well as age-old frictions in personal relationships and friendships.

As this slate of characters grapples with crisis, loss, and what it means to hold each other close in a rapidly changing Singapore, we are invited to ponder: if this is indeed how we live now, should we continue in this vein?

You can find the speaker bios at the bottom of this page. Enjoy the conversation!

Photo of the speakers (left to right, top to bottom): Yu-Mei Balasingamchow, Jinny Koh, Anittha Thanabalan, Rachel Heng

🌀

Yu-Mei: Good evening to everybody in Singapore. I’m actually calling in from Boston, Rachel is also on the East Coast, so we are both on 8 a.m. time. If we are a little slow, please forgive us, we will warm up very soon. Thank you for spending your evening with us to hear about the new anthology. I’m just going to make some kind of opening remarks about the thinking process behind putting together this anthology. I'll talk a few minutes about that. So I wanted to start by thanking Ethos for inviting me here and inviting me last year to be the editor. When they were like “Do you want to put together an anthology of Singapore short stories?” I was like yes please! I love reading short stories, I love talking about them. Sure, let me spend six months reading as many as I can. And then today here we are.

This book was about one year in the making, which isn’t a whole lot of time, when you think about it. Together with the editors at Ethos—and I want to give a shout-out to Suning and also Arin—we read as much as we could of everything that’s been published in the last five to ten years, sometimes going back a little further. And we were looking for stories that we hoped would say something thoughtful or interesting about Singapore today and also that would resonate with young people, because this book is going to be used in schools.

But when I was reading, you know, at night, in the daytime, at my desk, on my couch, in bed, I wasn’t thinking things like, oh, is this going to be a good O Level text? I was just thinking oh, what’s the story doing? Am I curious to find out what happens next? Is it drawing me in? Am I being moved, especially by the end of it? I think that emotional response is something that’s really important when it comes to reading. It’s actually kind of what we’re instinctively, unthinkingly looking for. And it can also be the thing that can be hard to express to people, like why you love a particular writer so much, or why you love a particular book. Because you just have this feeling, something that’s beyond words, right.

So coming back to the ten stories in this collection, at the very beginning of the project, before I’d read anything at all, I wrote down in my notes: Short stories are, by definition, small but capacious. And I think that’s what I was really looking for as I was reading and commissioning work for this collection. Small but capacious. People often say in Singapore—even now in Boston, I work in a bookstore, I talk to people, I try to convince them to read more short stories— they’re like, "oh, I don’t like reading short stories, they’re too short. They’re over just when you’re getting into them". And I’m a big novel reader myself, so I get it, right? You really want to sink into several hundred pages of an invented world and lose yourself there.

But I think the interesting thing about reading short stories, especially rich ones—and I think we have ten really rich stories in this collection—is that each one is almost like a mini-novel. It’s capacious, it’s rich, it’s capable of evoking a whole world, sometimes even multiple worlds. When you have a really solid collection of short stories, I don’t think it’s something you actually sit down and read cover to cover. I think it’s more like something that you can dip into when you just want a little something, a little sensation, just to feel something intensely for a little while. You read for maybe half an hour, you finish one story and you’re good. You’ve had this journey, you’ve been given something to think about, it’s all compressed into a very short, dense narrative and it’s enough. Those are the broader thoughts about stories and—when you put stories from different writers together in a fresh collection like this—things that can really make it pop when they’re all together for the first time.

What we’re going to talk about this morning with Anittha, Jinny and Rachel here are their stories, and what makes them capacious. But more broadly, talking about all ten stories, I think they really make the most of the potential of what a short story can do, and so in that sense they are all much bigger than a “short” story. They expand outwards into this really complex, fascinating, contradictory Singapore, much bigger than just what the one or two or three characters are talking about.

I just want to talk briefly about two of the “smaller” stories in the collection, by which I mean the shortest ones. So we have “Painting the Tiger” by Philip Jeyaretnam and we have “The Thing” by Yeoh Jo-Ann. “Painting the Tiger” is really about one character. He brings his son to the zoo, they look at some tigers, he thinks about tigers, and then the story goes on to open up this way of reimagining Singapore that is very powerful. And I just want to read you a little excerpt from the story to illustrate what I mean. And in this excerpt, we are with the main character Ah Leong, as he’s literally trying to paint a tiger.

“But how could someone born and bred in this city paint a tiger from his heart? Six hundred years ago the lion had been chosen for us, even though no lion had ever walked our land, as if our destiny as an imperial outpost had already been determined. When a few hundred years later the British came prowling, sniffing around the islands of the Riau, the lion was a perfect fit for the projection of the British crown’s power. The contrast between the lion (who dominates his pride by force of will, hunts in the day and overwhelms prey with the strength of an entire pride) and the tiger (who hunts at night, alone, relying on cunning as much as strength) illustrated the difference between Singapore’s orderly streets, with the first street lighting and sanitation in Southeast Asia, and the dark jungles all around. Not surprising, then, that tigers were ruthlessly exterminated.”

Most of Philip Jeyaretnam’s story is taking place in modern Singapore, then suddenly, boom, we have this brief historical excursion, telescoping out to a point of view about why is Singapore this way now, and then we’re back to Ah Leong and his painting after this, and we follow him as he’s painting. So that’s just one example of a really small story that takes you to multiple places at once.

And the other story I wanted to briefly mention, also very small but capacious, is called “The Thing” by Yeoh Jo-Ann. We have a father and a son dealing with an absent mother who has simply disappeared without explanation. The son is a teenager, and he starts knitting. And he knits and knits; he’s using black wool and he starts knitting this giant Thing, which is what the story calls it, and the Thing starts getting bigger and bigger and he starts carrying it around. And what is he making, what is he doing, what’s going on inside him… the story never actually tells us explicitly. Instead it poses these questions, it makes us think. And in particular it raises these really interesting questions about Singapore society, how people love and care for one another, or how they don’t, and as readers we are left to draw our own conclusions.

In my introduction to the anthology, I wrote that all of these stories pose questions such as what are we doing here, how did we get here, and what will we do now? And to be honest, these are questions that have haunted me personally for years. I used to do a lot of research on Singapore history, which gave me some understanding of what took place here on this island in the past and how it came to be this way. But over time I also became more interested in the question of what are we doing here, why do we still live like this, today? And what makes Singapore, Singapore?

In some ways, the ten stories in this collection offer a tentative answer to that question. None of them is self-consciously about being Singaporean. But when you read them alongside each other, you have this collage view of Singapore culture at this moment in time that emerges, so the kinds of hidden hopes and fears and dreams and energy, you know, things that are simmering below the surface, sometimes spoken aloud, sometimes not. The stories also show you very unexpected sides of Singapore. They take us to places that we think we know, and then they show us something else.

Just to use examples of the stories of the three writers who are here: Anittha’s story takes place in a wet market, but it is not about shopping for a family dinner, nothing like that. It's much more interesting. Rachel’s story takes place in a senior citizens’ home, and I don’t want to spoil it, but it is full of life and colour and… a lot going on. Jinny’s story takes place in a HDB setting, so it’s familiar; in some ways we’ve seen it before. But the relationships between her characters are very fresh. It also deals with serious matters, but it manages to do it without being heavy-handed. So there’s all these really interesting journeys into these spaces that as Singaporeans we immediately recognise, but then also it’s like eh, something interesting is going on here, let me turn the page and see what it is. Hopefully you will have that reaction too.

To quickly recap, the things I am broadly thinking about even today are: Is this short story moving me? Is it rich? Is it capacious? When you reread it, is your experience deepening? Does it get better when you read it a second and third time? Those are the big things that I’m often thinking about with regard to short stories.

In closing for my opening remarks, I just want to acknowledge the other writers I haven’t mentioned yet, whose work is in the collection: we have Dave Chua, Karen Kwek, Patrick Sagaram, Jessica Tan, and Yolanda Yu Miao Miao. Yolanda actually writes in Chinese, and we have an English translation of her story by Jeremy Tiang, who recently judged the International Booker Prize. Overall, it’s a really wonderful line-up. I hope you read them, I hope you enjoy them, there are some fun rollercoaster rides in there. Please take your time with each story.

Now we’re going to turn to our three writers, Jinny Koh and Anittha Thanabalan, and Rachel Heng. Each of them is going to read a little from their story, and then I’m going to ask them a little question about their process and so on, and then we’ll have a general chat about writing the short story, and we’ll have time towards the end to take questions from the audience. Let me hand the time over to Jinny.

Jinny: Thanks Yu-Mei! I’m first up. Hi everyone! So I’m just going to read two short sections from my short story. My story is titled “Close to Home”. Just a little bit about it. It's about a boy who was sent to live with his neighbour for a period of time because his mother was undergoing cancer treatment. So the story unfolds about his experience living apart from his family and trying to make sense of the mom’s diagnosis, and building an interesting relationship with his neighbour/nanny for a period of time. I’m going to start with the first page of the story:

“The year my mother was diagnosed with ovarian cancer, my father sent me to live with my neighbour Aunty Loh. He said he couldn’t drive his taxi, ferry my mother to the hospital and take care of me. It was only temporary, until my mother finished her round of chemotherapy, until things “settled down”.

It was 1998. I was ten and didn’t want to live in a stranger’s home, although to be fair, Aunty Loh and her family weren’t strangers. We had been living next to each other in the same block of flats in Pasir Ris, the east of Singapore, for the past decade and had chatted a few times along the common corridor. Still, I would have protested against my father’s wishes if not for the fact that my mother had become so frail she could no longer get up from bed. Her body, once plump and supple, was now loose and gaunt in her pajamas. I didn’t want to add to their troubles.

It was, perhaps, also my mother’s wish that I didn’t witness how her illness had debilitated her. How she needed to grab the red spittoon beside the bed every few hours to throw up, or how my father had to carry her to the bathroom for her most basic needs. The day I left home, I noticed that the small bald spot on the back of her head, at first a circle no bigger than a fifty-cent coin, was now an uneven patch the size of my fist. Her eyes were red-rimmed and watery as she waved goodbye, promising that she would bring me back soon. She had begun her second cycle of treatment.”

So after this he met his neighbour, and I’m going to skip a couple of pages after where he returns home to his family for the first time again.

“It was odd living in a house next to my parents yet not being able to see them as I pleased. Since I didn’t have the keys to my own home, I would peer outside Aunty Loh’s window at the common corridor, hoping to catch a glimpse of my mother. I never did. Thankfully, my father brought me back every Sunday evening, and I would lap up our brief moments like a thirsty dog. My mother often asked if I was adjusting well at Aunty Loh’s, if I was eating enough, if I had done my homework. I would talk non-stop, filling the gaps of silence with my mindless chatter, hoping to keep her awake for as long as possible. She grew steadily weaker, dozing off in the middle of our conversations, and each time her eyes closed, I feared they might never open again. The grey bags under them were dark and heavy against her sallow cheeks, her pasty lips stretched thin each time she tried to smile. Even her eyebrows had fallen away. The first few weeks I visited, she wore a brown woollen hat which I’d never seen before and would scratch her head every few minutes. One day, after a particularly bad itch, she removed the hat and told me not to be frightened. I said I wasn’t, and that was true, although I thought she looked strange, like an alien, a faint blue vein pulsing behind her ear, her bald head smooth as the back of a ladle.”

Those are the two sections.

Yu-Mei: Thank you very much. That ‘smooth as a ladle’ line, it always [hits it] for me; the mom is so sick when we hit that moment here. So just a quick question about your story. You have a number of very striking female characters: the mother, whom you were just reading to us about; Aunty Loh, who you mentioned at the beginning; and during the story we also meet Aunty Loh’s daughter, Pei Fen. These are really striking women, but you chose to tell the story through the point of view of a ten-year-old boy. And I was wondering why you chose this point of view, why it’s important to you, and also maybe why you decided to set the story in 1998?

Jinny: The first part about why I chose a male protagonist - this story was inspired by my husband’s childhood. When he was telling me about it, what happened was he was actually sent to live with a neighbour who became his nanny, and he only returned home during the weekends. When he told me that part of his childhood, I was very fascinated in a sense, because right now we seldom hear of such arrangements. I am a parent myself, and I can’t actually imagine doing that. For most of us, we send our kids to childcares, and to send them away for the entire week is really not so common. That really inspired me to think about what his experience was like. And of course, other parts of the story and all the trouble that came about later on is fictitious.

The starting point was to hear my husband telling me about his time there. He was a baby when they sent him there—I mean, when he was a toddler they brought him back home to live with them. But that made me very curious about the experience, so I decided to set the story with a protagonist that was older—10 years old—who was able to analyse, observe a little more, and who could be a little more active as well as a character. That was what happened, how this story came about.

This thing about setting stories in the ‘90s is something that is very personal to me; maybe it’s a penchant for this nostalgic era that I grew up in. Even my novel, The Gods Will Hear Us Eventually, was set in the ‘90s, when I was a child. They say that us millennials went through this short, brief period of time when technology became super fast, and our lives are so changed now compared to just twenty years ago. The internet changed everything. There’s this fondness in me to relive the past a little bit, and I can do that through my stories. The sights and smells of Singapore, what it was like before we were all addicted to our phones, what did we really do on a day-to-day basis, how did we pass our time. All those things really fascinate me and that sense of nostalgia really brings me back again to that period of time, that I just want to capture and immortalise into the pages of a book.

Yu-Mei: Thank you! That was a really great overview of how you came into the story. Also really interesting what you said about time. Maybe we can talk about it later when we do the group Q&A; how writing a story is a way of time travel for you as the writer, because you’re trying to bring back this period and what it felt like before we got addicted to our phones. And then also what the experience might be for the reader when they are transported by your story. Thank you very much!

From a ten-year-old boy, we’ll go and look at some teenagers. Anittha Thanabalan has a story with two very (if I may say so) vivacious teenagers.

Anittha: Hi! Okay my story is set in a wet market, which I think a lot of people—a lot of teenagers—probably haven’t been to, especially recently. So it’s about these two best friends who are in a wet market every Sunday, and it’s what happens to them one Sunday. So I’m just going to read the excerpt really quickly:

“Finally, Gita wandered casually over to the mutton stall. There was a moment’s lull, no customers were waiting. She scooted by the smelly, deep bin. Then she grabbed Ramani’s apron, yanking her down from the high step, and pulled her to the back of the stall.

“What is wrong with you?” Ramani demanded, prying Gita’s fingers off. She tried to stand, but Gita pulled her back down. They were surrounded by Styrofoam box towers. Unless someone wiggled past the bin filled with meat trimmings, it was impossible to see them.

“I told you to check your phone, and I gave you the five signal!”

“What?” “The five signal? We’ve discussed this before. You know DEFCON one, two, three, four, five?” Gita flashed the corresponding number of fingers in Ramani’s face.

“You do know that DEFCON one is maximum urgency and DEFCON five is minimal urgency, right?”

“But I’ll look stupid jabbing one finger in the air.”

“Do you think you looked like a genius wagging your hand like a tail?”

“Shut up.” Gita took a deep breath. “Look, Eileen is here.”

“Who?”

“Eileen. Eileen Tan.”

“That short girl with the tall friends?”

“Yes!”

“The one that thinks our mother tongue is ‘Indian’?”

“Yes.”

“Okay. So?”

“We have to go. She can’t see us here.”

“Why not?”

“Because she’ll take a Story or a picture and post it. And

everyone will know what we do on Sundays!”

“So?”

“We promised never to tell anyone what our parents do

for a living.”

“We promised never to tell anyone what your parents do for a living. I’m proud of my parents. It’s an honest living.”

Their faces carried the same frustration.

“Eileen is in the market, right now. Even if she doesn’t come to my parents’ stall, she’ll go to Aunty Maisarah’s or Aunty Ling’s. She’ll see you. She’ll see what you’re wearing.”

Ramani stood up. A long grey rubber apron hung to the tops of red knee-high rubber boots worn over leggings. When she moved, the apron rubbed loudly against the boots, like a toddler’s squeaky shoes. “I call this wet market chic.”

“They’re not even the same colour! Please don’t go, okay?” Gita stayed crouched and squeezed her hands together. “Eileen knows we’re friends. I’ll be dragged into it with you!”

Ramani glared at Gita. “Dragged into what? I’m helping your family as a favour to you. And now you want me to abandon them so that you can save face from a girl who can’t even tell us apart?”

Gita’s eyes went wide. “OHMYGOD! She’s going to think you’re me!”

Yu-Mei: Thank you very much. The snappy dialogue in that story, it’s—ugh. Those two girls, young women, very alive.

Your story also has an interesting, behind-the-scenes origin story of its own! I read an earlier version, where Gita and Ramani were involved in something else; partly supernatural, family heirloom. And then I asked you if you would like to expand this story to tell us more about the relationship between these two girls, because it’s so hard to write well about adolescent friendship, and there was something in the earlier story that was simmering. Maybe you can tell us how you decided to go from the earlier version to this? And also all the elements that you brought in. You just showed us in your excerpt this classmate who can’t tell students apart because they’re all “the same”, which is ridiculous right? And their concerns about their parents being hawkers at the market and what their friends will think?

Anittha: The earlier version like Yu-Mei mentioned was more of a parable, so she wanted me to explore the friendship which I honestly enjoyed. It’s opposite to Jinny, because Jinny wanted to go very nostalgic back to the ‘90s. I also grew up in the ‘90s, but I always wonder about teenagers today because I feel like all the access to all these tools that they have now—Instagram Live is a great example, the idea that at any moment if I want to share something about a friend, that I can just pick up my phone and just go live, and there will be [people watching]. I mean if you’re not an influencer, I understand there will be smaller amounts [of viewers], but it’s still an insane concept to me.

One of the characters in “Live! At The Wet Market” is Eileen. She eventually goes on Instagram Live, and she shows what happens. As you get older, I’m so happy that I didn’t really have all this growing up, because there would be so much stupidity of myself just forever online, and at least I don’t have to deal with that. I wondered how teenagers would grow up with all this, and we are never going to escape from it. That’s what the story really captures. And the friendship element as well, with all of this that exists around you. Because ultimately, I feel that there’s a lot of friendship and adolescent lessons that don’t change, but technology is a very interesting addition to all of that. And technology that you can stream from anywhere is insane. I just wanted to explore what that would look like, and how that would ultimately affect friendships.

Yu-Mei: Yeah! I’m trying to think about how I can speak about your story without giving things away. It has all these very “of the moment” elements. But some of it, like you said, teenagers being insecure in some ways with their relationships, in school, all the dynamics. We all recognise that, even though I’m older than the two of you and I remember what school used to be like.

Anittha: I also wanted to look at parents, because [in the story] both parents are wet market vendors. They sell meat or flowers, and I wanted to look at that dynamic as well. Imagine having those conditions and now you have technology. Which I know is not often considered, but on a very basic level, how does that affect your day-to-day life?

Yu-Mei: Thank you. We’ll turn next to Rachel, who’s going to read us a little bit from her story.

Rachel: Hi. As Yu-Mei kindly pointed out earlier, we are on 8 am time, so forgive me if I sound asleep, but I’m awake now, I have coffee. I’m going to read from my story, “Before the Valley”.

“The candles were already lit when Hwee Bin arrived. Her mistake—she’d missed the announcement at breakfast saying today’s party would take place in the Big Hall, instead of in the Rec Room. What was wrong with the Rec Room? she mentally complained, while taking her place in the crowd. Birthday celebrations were always in the Rec Room. But, catching a glimpse of potbellied Kirpal in his wheelchair, Hwee Bin softened. Likely the change had been made because Kirpal was so popular, and more residents than usual were expected to attend. Typically, birthdays were local affairs. Hwee Bin was in Ward 4, one of the fourteen-bed wards, which was a bad thing every day of the year except her birthday, when it meant that she could count on at least thirteen other people showing up to her party. A relief, since Hwee Bin had never been good at making friends, even before.

“Before” was the shorthand residents used for their lives prior to Sunrise Valley. Before wasn’t talked about often; it felt unseemly somehow, self-indulgent, to dwell on one’s past life. What did it matter, for example, that Cynthia, from Ward 8, had been an actress who starred in the horror films that used to be made here in Singapore, back in the sixties? Or that Hasmi, from Ward 12, had been a lawyer and was even rumored to have owned his own firm? They were all here now, Sunrise Valley residents one and the same. Sure, Cynthia was in a two-bedder with a garden view, and Hasmi had one of the few, coveted, and very expensive single wards. They still had to come to the linoleum-tiled dining room each morning for the same soggy kaya toast and watered-down coffee. Still took their seats each evening in front of the television, which blared, alternately, English-, Chinese-, Malay-, and Tamil-language soaps. Wards aside, were the residents not all in the same boat? The details might differ—mild dementia, children too busy to visit, loss of leg function, no living relatives—but the crux of the matter was the same. You were stuck in Sunrise Valley regardless, whether it was paid for by your dwindling pension, the government, or an erstwhile child.”

Thank you.

Yu-Mei: Thanks Rachel. That selection you picked gives us a portrait of the Sunrise Valley residents really vividly. Your story is so interesting because it takes place in a space we don’t often see in English literature in general. Basically a home for senior citizens, older people who are not allowed to live on their own, or can’t, depending on the circumstances. And then in an earlier story “Vegetarian,” you also wrote about a character in a similar setting. I was just curious; what drew you to write about this space, where did the characters come from?

Rachel: It's interesting you mention that story earlier, the earlier story, “Vegetarian”, because when I wrote this, my husband said, “Oh, you’re just writing the same story again.” But I maintain that they’re different, they’ve similar characters, similar themes, similar settings but I think they’re different stories.

What draws me to them is, I think we write towards what we fear, or a sense of loss or something that we’re trying to recover, which is something both the other writers have mentioned as well. For me, where my writing comes from is this fear of death, and mortality and loss. I think a lot about what it would be like to be this age. Obviously I haven’t lived through it. I’ve witnessed older relatives and not-so-old relatives pass, unfortunately, and reckoning with that and thinking about the strangeness of time and life in that period before you know that death or illness is imminent, and what you choose to do with your time and what are the relationships that remain or what are the conflicts that still remain and how very often, we are still inextricably ourselves in that moment. We don’t become better people; even if we know that we don’t have much time left, we can’t fix all of the dysfunction that’s happened in our lives. Those relationships still stay fraught, and you try and you try, and it’s then it’s even more poignant or frustrating, and maybe you have one moment of grace, but in general, life is as it always has been, and then it ends.

Sorry this is a real downer of an answer, but that’s where I get to when I write these stories. I do return to it again and again because maybe it is a fear of my own. It’s kind of an obsession.

Yu-Mei: That's a really honest answer. I appreciate it, and it also [gives us] a lot to think about, [such as] what are we writing towards?

I’m going to just throw a question out, and any of the writers can respond in any order, and also if you want to pick up any threads from what each other were talking about. Bridging from what Rachel was saying, each of you is writing characters who are not like you; they’re significantly older or younger than you. So much is imagined, so much is you trying to feel that thing. What is your way of making these details about Singapore life so vivid and real? Since you are not living any of these particular lives. How do you inhabit these worlds of people who are not like you?

Anittha: For my story, they’re Indian girls. I was an Indian girl, so it wasn’t particularly difficult. But I do think that when it comes to writing, it’s always fun to try and empathise as much as I can. I think empathy is really important for writers in general—people in general, of course—but especially for writers. So I try very hard to think about myself in the same situation and how I would react. That also helps trying to figure out their voice.

Jinny: For me, I think I draw a lot from my own personal experience. Sometimes they say that there are certain writers who like to write speculative fiction—not saying that speculative fiction doesn’t have the same kind of observations about human life—but for my own stories I tend to veer towards the more realistic kind of stories, things that are very day-to-day slices of real life, and that sort of thing. I draw from a lot of my own personal experiences and observations and the people around me, and I like what Anittha mentioned about how we need a lot of empathy when we approach our characters. Whether we’re writing about a young boy or an old lady in a nursing home, or we’re writing about a father or mother, I also try my best to really be in their shoes. And at the end of the day my compass is always that we’re just writing about the human condition, and whoever you are, it goes back to that whole idea. What happens when we’re put into a particular situation, or our characters are stressed in a particular way, and how we respond would differ, but again we’re all humans. And there are certain similarities that tie us together, when I think about it in that framework or paradigm.

Rachel: For me it often comes back to the physical and what it’s like in that character’s body. And obviously I can’t know, if I’m writing a character who’s 80 years old and in a senior citizen’s home. But try to really situate yourself, to think about the senses, and what it feels like on the skin, or what does it feel like to stand up, or to look at something or what food you want to eat. Even if those details don’t go in necessarily, the way that they situate you in that character’s point of view always helps for me.

And then this is an exercise that I sometimes assign to students when I’m teaching characterisation (which is when you write a character): to give them one characteristic that you absolutely don’t have. Give them an opinion that you don’t share, the opposite of yours, and give them one thing that you do share. Have them love something that you love deeply. That’s a way of getting into a character and empathising, but also getting out and having them expand beyond yourself. So I try to do that sometimes when I’m stuck as well.

Yu-Mei: Thank you. Interesting that you mention that, because I’m writing a novel and a lot of the time I’m thinking about that very thing, like "oh this part I agree, this part I don’t, I am totally not like the character that I am writing about". But it’s a good compass to tell yourself; you don’t veer too far off but you also want to give the character its own life. They get to be their own full creation, not just one thing.

I’m going to jump to one of the questions that someone has posted because it’s a good bridge. How do you devise dialogue – do you think of the characters first and what they would say? How do you lend them an authentic voice?

So an “authentic voice” might be something we can also talk about. What constitutes “authenticity” in fiction, on the page? All of you have dialogue in your stories so this is the perfect thing to ask now after talking about characters.

Anittha: With dialogue it’s always really difficult. I remember I used to watch a lot of Masterclass online, the site. I bought the one that Neil Gaiman did, because it’s Neil Gaiman. I remember he said that if you want to do dialogue, you gotta listen to your character. I thought that was very interesting because I never thought about that before. Usually I’ll try to put words in their mouth. So that’s something that always stuck with me.

When I was writing this particular story (and everything else I’m working on when it comes to dialogue), I always read it out loud, and then I try to respond to myself. I find that really helps, because no one really talks like how they write. I try to do that with my characters. I find it’s really helpful, and it makes it more authentic, I suppose? You drop certain vowels and certain words. You will not say “I had gone to the market yesterday”. Things like that. I try to be very mindful of that. When it comes to authentic voices, that’s a really big question, because it also links to… I know there’s this whole thing happening online of who should be able to write authentic voices. But I really think it comes down to empathy again. If you do enough research and if you have sensitivity readers and all these things, you can write almost anyone. Including people that you also don’t entirely relate with or don’t really share the same life experiences, and it does help a little bit to just see what’s out there.

Jinny: This is a really interesting question, because I find that dialogue is a really difficult thing to write. I feel like most people struggle a lot with it. When I teach my students, I also tell them that dialogue is one of the most difficult skills to acquire, at least that’s how I feel. I’ll tell them that if you’re not careful, all your characters will sound the same, and they’ll sound like you, because when we’re writing our characters, we write it in our head. I like what Anittha shared about how she’ll read it out loud, and that’s really one of the ways (it’s almost like a litmus test) to see whether your characters are all sounding the same. Personally for me, the way I avoid that is to again, try to read out loud as well.

I won’t use the word ‘eavesdrop’, but when I’m outside, around people, I try to hear how they speak and how they talk. This is something that I learnt when I was doing my Masters in creative writing as well. I really like what my teacher taught me which is always listen to what people are saying and the way they are talking, because no one sounds the same. Whether you are sitting in a fast food place, or the hawker centre or the restaurant, getting their order taken, just hear the different voices. After a while, you form this invisible catalogue in your mind. If you want to pull out a certain character—it’s a little stereotypical, so that’s another thing to be careful about. You stereotype different people, the way they speak, but that’s where editing comes in. As you edit, you hone them and model them into a different person. To me that would be a good starting point.

Yu-Mei: I would also say that I totally own up to the fact that I eavesdrop all the time. I’m not shy about it. It doesn’t mean I’m going to use what I hear!

Jinny: Exactly. We’re not exposing people’s secrets everywhere, but we’re just observing our environment.

Yu-Mei: And it’s what you say about the feel, right? When we’re writing at home individually, it’s us and the computer or the inner voices of the characters. We can’t test it out like “hey, you come and play the character, I test it on you.” We’re creating that from nothing. But when you observe people in real life having a conversation, you can see all these two-way, three-way dynamics going on that are fascinating. No one is ever going to have a secret conversation around me again.

Rachel: I was just going to say, that was an exercise a creative writing teacher assigned me once, which was to go out—well, not me specifically but the whole class—to go out and eavesdrop on conversations and write down exactly what they say verbatim. Because then you realise it’s strange, exactly like Anittha was saying. People talk like how you don’t think they talk. Or in your head they talk a certain way, and if you actually listen to what they’re saying, it’s very different. The way that they interrupt themselves or each other, or they don’t listen to each other, or the subtext of what they’re saying and the ways in which they’re trying to get something or appear a certain way. It’s very fascinating. I don’t do it anymore. I should, actually, now that I’m talking about this in front of everyone. That’s probably how I should do it and how I would give advice on how to do dialogue. Just listen to people and take notes.

Jinny: Half the time we’re just winging it.

Yu-Mei: Shh! But winging it is the best, because that’s how we find new serendipitous solutions to whatever is going on on the page.

I was just going to pick up and say—because Rachel talked about this creative writing exercise and how people talk—we talk in circles and we repeat ourselves. There is this distinction between how people really talk (if you’re going to record them) and what appears on the page. If you put too many of these repetitions on the page, the reader might feel "eh, I already know, I read this half a page ago. Why is the writer making the character repeat the thing." This is not good dialogue, because the reader might get impatient. So coming back to the question of what’s an “authentic voice”, there is this question of “realism” and that in fiction, you’re not necessarily always trying to replicate realism but evoke it.

Jinny: I totally agree with what you said about how we’re not supposed to replicate it verbatim, but we’re supposed to process what they say and rewrite it so that it sounds succinct enough, yet realistic. And that goes back to editing, you know the entire conversation may be “15 minutes” or so but on the page we’re only allowed 30 seconds to 45 seconds of writing on a page for readers. And it should encompass everything of what a 15-minute conversation should hold. So yeah, to me it goes back to editing.

Yu-Mei: The fresh thought that I had as I was listening to Jinny is, what makes a character authentic is that we, the reader, believe this character would really say that or feel that, as opposed to a specific phrase or something. It’s more like “oh, we get it, you’re speaking from the heart, you’re really angry right now, or you’re really happy right now and, you know, that’s exactly what you would say. Of course.” That level of aesthetic authenticity I might say, as opposed to some sort of cultural or whatever it is that we sometimes get hung up on.

I had a question, again, related to dialogue, on writing about Singapore, and the fact that people who are not familiar with Singapore may read your story and may not be familiar with the wet market or with certain Singlish phrases, for instance. Whether this is something you even think about. I think there is a lot of unnecessary hand-wringing, as I call it, about “oh, people won’t understand Singlish if you put it in your stories.” I disagree vehemently. But to the panellists: do you think about how your story will be read outside Singapore, do you think about how much Singlish to put in, do you think about how you describe a place and who you’re describing it for?

Rachel: I can say something since I’m not in Singapore, and maybe Yu-Mei can jump in as well. If you are writing about Singapore and you’re not in Singapore, and most of your colleagues or readers around you are not Singaporean, it’s something that you are always navigating and something that I hand-wring to myself about. You veer between “oh will they understand it” and “why am I explaining it to anyone and why do I need to explain it to anyone”. Or "who am I writing towards" or "am I getting too much in my head because these people who don’t know this who are writing" so it’s affecting my writing, and I’m writing in a way I don’t normally write because I’m writing towards someone who doesn’t understand it. And you know the existential crisis that follows.

I think I just try not to think about it, and try to think about writing for my first readers, who are usually very close friends, most of whom are Singaporeans or who are very familiar with Singapore. For things like Singlish, if we never write it then no one will ever understand it. So if it feels right for the story—at the same time I don’t want to be like oh everyone has to write Singlish so that it is “authentic”, because it’s not, right? What would be the most capital-A “Authentic” Singaporean story; would it be an entire story in which the narrator is also speaking in Singlish? People have done this beautifully, but at the same time, not to preclude everything else, [do what] feels right for the story and for your ideal reader, whoever that is. For me, it’s often someone who is a close friend like me, or someone I grew up with. The people whom I want to be reading my stories, I write towards them, and [I'm] okay with the fact that there are people who aren’t going to understand it, or there are going to be people on the flipside who think I’m explaining too much, saying too much or making too many concessions to a reader who doesn’t know this setting. I make my peace with that, and do the best I can.

Jinny: To be concerned whether people will understand our culture and our language actually weighed heavily on my mind when I was a younger writer. For instance when I was doing my Masters program in LA, I had to write stories for the workshop, and I was very self-conscious that my friends or my teachers would not understand what I was writing. So for my first couple of stories, I set everything in the West. I had white people as my characters, they all had white names and they were doing white things. It didn’t turn out very well. Not that we cannot write characters in the West, but there was this barrier that I couldn’t access because I was really self-conscious. I felt like I had to fit in. Whatever I write, I felt I had to write in a way that they would understand my story. And it came out artificial for me. When I read it, I knew it, and still I submitted it.

It was only in the second month or so that I decided to just set one story with a Singaporean character inside. I was really surprised that everyone enjoyed it and they understood it. Then I got bolder and decided to write an entire story completely in Singlish from a first-person voice, and they could understand that as well. The only thing that’s stopping myself is me and all these fears or insecurities or the feeling that you have to write what people want or understand. That was a great lesson for me, that I can write stories that I’m familiar with, I can write characters I’m familiar with, and again back to the idea of the human condition, as long as we are talking about people, suffering and things like common themes, you will be understood. Over time, as I read more authors who also write about their own culture and do not over-explain their stories, like Junot Diaz, I realise that it is possible. And that really gave me the confidence to do it.

Anittha: I really resonate with what Jinny said. I think we all grew up reading a lot of white authors, typically. I didn’t read my first non-white author until quite late in life. The first one was The God of Small Things by Arundhati Roy. And then there was a lot of Anita Desai as well. And others.

When I was starting off writing, I was a lot like Jinny. I would give my characters this fake British accent in my head that I had to put down on paper and it was ridiculous. Ultimately that process was really helpful for me because I realised it’s the opposite of authentic and I sounded insane. Writing like yourself or representing yourself on the page is also liberating. I teach English Literature tuition, and when I see my students reading stories with Singaporean characters or different ethnic groups, disabilities and so on, it’s so nice because it’s not just one person, one ethnic group on page anymore, and that’s always really great.

When we were growing up reading books by white authors, we never wondered about their practices. It didn’t bother us nor stop us from reading the book. Judy Blume used to write a lot about the landscape of America. I never wondered what Walgreens was; it never bothered me. I knew that it must be a supermarket or some sort of shop. So I don’t think writing about Sheng Siong, for example, is going to bother anybody.

Rachel: In school you have to read Shakespeare, and we understand that context. So yeah, Sheng Siong should not be that controversial.

Jinny: I totally get what Anittha meant, when she said that right at the start, it was all these British accents in our head or American accents when our characters are speaking that way. And like what is this, who is this?

Yu-Mei: Yeah, that also made me think about the writer Marlon James who won the Booker [Prize] a few years ago, and in the interviews he’s given, he talks about how when he was starting out as a younger writer, and he had this voice - kind of like what Jinny and Anittha were saying. You think you have to write with that proper British, perfect diction, [a] certain kind of syntax... and it was constraining him; he was not writing well. Once he shook that off, like Anittha said, it was liberating. Suddenly it was like "oh, I can speak with my voice, and my voice wants to tell these stories", and his writing became more powerful. That’s also a really important thing for us to remind ourselves when we’re feeling a bit cornered, that nobody understands us, but to just have faith that your own voice might actually be enough here.

There’s another question from Yolanda, one of our contributors, who asked: “How do you deal with dialect vs. a local or international readership?”

Just to bring it together in the context of what we were just talking about (Singlish and other cultural elements), part of it is that people can look things up themselves, maybe? Part of it depends on how pivotal the emotional point is? I often think about that when I’m in my own writing, or reading someone else’s story which might come to me from a different world that I’m not familiar with, from parts of the world I’ve never even visited. And just like "oh, this word, I can tell it means something important, I don’t know exactly what it is, but I can tell that in the argument, this is the dealbreaker, and how the characters react", it’s good enough. I don’t need to actually consult a dictionary even though I could, because I’m feeling it. The writing is already moving me, it’s not that one word, per se.

Maybe if you spoke that language, or you were from that culture, that word would zing to you a little more, and you have extra layers of perception, but not all of us need that all the time when we’re reading. That’s one thing also that I try to remind myself: my readers don’t have to understand everything in the story. They just need to understand enough for that emotional movement. And it’s okay to have some gaps because they can sometimes fill in some of the gaps themselves, and it’s not a test where you need to understand all these things about Singapore to get the story.

So yeah, just being comfortable with some space, for your reader to fill in themselves. Or for them to not know and be okay, because they’ve got so much else to work with in your story. That sometimes is useful too.

I’ll jump to another question:

“How do you find inspiration and stay motivated when writing about Singapore, a place that seems mundane yet so familiar to us?”

Anittha: Singapore does feel very boring especially if you’ve lived here your entire life. It’s also very small. But people in general are very interesting. If you really tap into someone’s opinions, the way they look at things, and their perspectives and what shapes them, you could write that for a long time because it’s so interesting to see what shapes someone. Even though the landscape doesn’t change, the person always does. We all take different things from this country; our perception of it, societal values, and individual values based on societal values. Do they accept it or do they not? Different things happen. That is what makes it very interesting, because people always surprise you.

Yu-Mei: The human condition as Jinny was saying earlier.

Jinny: I don’t feel like Singapore is very mundane. On the contrary, because we’ve progressed so quickly in the last few decades, there’s so much to mine from the population, if you talk about character building. It may feel like on a day-to-day basis, we all seem to be pursuing the same things. Maybe that’s the kind of dryness and mundaneness that people talk about; there’s no variation in what we think is a good life in Singapore. But because of this progress in the past few decades, there are so many different groups of people that we can observe and write about. Who are left behind in this pursuit of progress? Who have moved forward, and what are their lives like? So on and so forth. So I never felt like Singapore was very mundane for writing. There’s a lot of things that we can be inspired by, at least for me.

Rachel: I would agree with that, I don’t think Singapore is mundane at all, I think it is very strange, fascinating, and interesting. And I would hazard a guess that [for] the person who sent that comment, there’re probably parts of Singapore that you also realise are interesting or weird or fascinating that you don’t think about. The “oh Singapore is very boring” is a throwaway thing that people say, or rather we’re all used to saying that. I don’t know why but I feel like I grew up hearing it and I thought that too when I was young. Maybe it comes from being a teenager and being like "oh my god, where am I going to go again? Am I going to go to Wisma Atria one more time?"

You know that feeling, and moving past that feeling and thinking about the things in your life that is interesting to you. People have fascinating lives in Singapore. It doesn’t have to be interesting with a capital-I to everyone, but everyone has their little obsessions. If you look for characters or people who are passionate about things. The other day I was reading, there was this guy, I think he lives in Upper Thomson or something, and he has a collection of fossils? There’s a Singapore fossil collecting Facebook group. So there are all these little things, and there’s people who are very passionate about that one thing that they do. Especially in such a dense place, where there’s just so many people and so much stuff happening, and all of that history that is concentrated in one place.

This is not a very helpful answer from any of us, because we’re all like, "it’s not mundane haha".

Yu-Mei: That is precisely it. The eyes that you bring to the scene in front of you, right? And I also think of it also in terms of attention. Obviously if you’re going about your daily life wherever you live, you cannot pay attention to everything at once, because you need to get your life done, take the bus, go to work, whatever it is. But for me, when I started writing more fiction as opposed to non-fiction, I was starting to pay attention differently, I noticed that in myself, because I would be sitting at the bus stop, watching my neighbours and neighbourhood. I would notice different things that I would not have noticed in the past, and realised that "oh, I wonder why that person is wearing that outfit, and how would you even begin to put it together and what do they do the rest of the time?"

And wondering, (not that I wrote about that person), who are these people moving around us. Or even looking at our HDB landscapes; “it’s all the same” is the knee-jerk reaction. But if you actually sat and looked and paid attention to the different parts, and brought that attention to any landscape—you could be living in what seems to be a flat monochrome desert, and if you paid attention you would find things that were grabbing your attention at the corners.

Sometimes I think that—going back to what Jinny was saying earlier about Singapore being high-tech, fast-paced—it’s easy to not pay attention because there’s so much going on, and it’s almost like we have to deliberately slow down a little bit to be like "oh wait, I want to linger here for a minute because I really like looking at that thing, or observing that person or eavesdropping on that conversation". How many times have I stayed longer at a table until a conversation is done? Not taking notes, I’m just listening until they leave. You know, making time for those little interactions. At least that’s my reaction.

Rachel: I also think that the sameness itself is interesting. Like what you were talking about, the HDB blocks are always the same. That's the beginning of a story already. I’m like "ooh, why is it all the same"? Or what happens in that sameness?

And the other thing is going back to what Anittha and Jinny were saying about writing white characters or white stories. And that instinct of "oh there are no stories to be told here in Singapore", that it’s mundane, it’s that idea of what stories are worth telling, right? What is a setting in which a story is worth telling? Does it have to be in New York City where then it’s exciting or interesting? We have this instinct because you just haven’t read that many stories told in this supposedly mundane place, maybe. Then it’s up to you to make it interesting, right? Or bring that attention to it and like say "hey, I’m going to tell this story about this supposedly really mundane thing and make it worthwhile" and people will read it and hopefully, ten years later, no one will say that Singapore is mundane anymore because you’ve changed that narrative.

Yu-Mei: Thank you. That is also a really good point, changing the narrative. Which leads to this other question from Wai Kit:

“If you had the chance to extend your story, what would you have liked to include (more of), and why?” If anything?

I would build on that to say Rachel just made this point about changing the narrative. Beyond your story in this collection, what other things interest you that you haven’t yet written about?

While the panellists are thinking, I will hazard a short reply to Wai Kit’s question about the chance of extending a story. I also write short stories, I’m working on a novel, and for my short stories, I have never wanted to extend a single one of them because I felt that for me, as a writer, I had come up with these imaginary characters, given them some stuff to work out, they’ve done it within, usually, 6000 words, sometimes less (rarely), and I’m good. I’ve sorted that out for them, feels like it’s the right size, finished! I know not every writer works like this, but for me, a short story in my head is very different from my novel, which can go and go and at some point you’re like "ahh, too many words". It’s a different feeling, perhaps a different interest level. When I write a short story, I just want to know that moment in that character’s life. I know what their backstory is, but I don’t need to write it out on the page. Whereas with a novel I’m like, "this is a bigger question, these are three or four or more strange dynamics between characters, I need more space to write it". So that’s just me. Throwing it open to the panel.

Anittha: I agree with Yu-Mei. When you start writing, or if you’re a writer in general, you don’t finish a lot of your stories. I start a lot and I don’t finish a lot; they’re just half-written in my computer and waiting for me to continue them. It’s so nice to finish a story, especially a short story, that I would never want to extend their life. Like "okay you’re done, bye". That is how I look at it.

Rachel: I agree. If a story works for me, then I don’t want to extend it. If I want to extend it, that means it’s not working. So either it becomes a novel or I do not finish it, as Anittha said.

Jinny: I agree with Anittha, Rachel and Yu-Mei as well. I thought it was a fascinating question because I have never ever thought about extending any of my short stories. I always feel like short stories are a different animal from novels. Novels can have a second, part two and part three, but for my short stories, no matter how much I like a particular character in a story, I never thought of extending its life, you know, put him in another scenario. Whatever has happened in that episode, I’m really happy with it and satisfied with the trajectory of that person’s life and, especially for short stories, we usually put a lot of thought into the ending. It has to end in a certain way that is impactful, and so when we’re happy with the end (or at least for me) I seldom think of extending it. Like what Rachel said, if I have to extend it, then there might have been something wrong with my ending that requires that.

Yu-Mei: Great! Does anyone want to respond to this idea of changing the narrative and stories that you haven’t written or you hope someone will write? Things that will make Singapore seem not mundane at all?

Anittha: I don’t know about changing the narrative, I feel like anything that anyone writes from any perspective will be adding or changing the narrative in general. Because everybody has different ways of doing it. It does happen eventually when you keep writing and you’re not afraid to put out ideas that feel odd or different.

Jinny: For me it’s not so much of changing the narrative as to adding more diversity in the voices, which I feel like is happening in the recent years with the explosion of SingLit. I feel like we’re in the right direction, SingLit as a whole, as a community, and as a community of writers. So I feel like it’s not so much about changing it but building on it with more diversification.

Yu-Mei: We’ve covered everything that came from the audience. Maybe we will wind down then, and let me ask the last question which I’ve stolen from a podcast I enjoy called the Ezra Klein show, where at the end of his interviews he always asks about books of his interviewees. My question to the panellists is: what is one book that has shaped your thinking about fiction writing, and what is one book of any genre that you wished more people would read?

Jinny: As a really young writer, I was really impacted when I read Yiyun Li’s short stories [collection] A Thousand Years of Good Prayers. What really fascinated me was her treatment of the characters. They were really fascinating. She had an old lady, then this story about a fake emperor and stuff like that. She really opened my eyes to good storytelling. The one book that I wish more people would read—which actually I don’t think many people have read, or at least those in the writer’s circle—would be Miranda July’s stories. She has a short story collection called No One Belongs Here More Than You. Her characters are super quirky; they really force me to think outside of the box, you know, the kind of quirks and strangeness that a person can embody.

And speaking of that, I would like to say a second book, even though your question said one book. But I really like Aimee Bender’s short stories as well. More than her novels, actually. Her short stories would be almost like fabulist fiction? And her characters are really crazy. There’s a boy with an iron for a head. And all these really interesting, quirky things that is different from my style of writing. When I read it I feel like it expands my own style as well. I may not adopt everything that they do or I may not write speculative fiction, but just being exposed to that changes me as a writer as well.

Rachel: I know Yu-Mei actually sent us this question beforehand, and I kept putting off figuring out the answer to it. I was going to say for the first question (what affects my fiction writing), and now that Jinny’s answered it I’m like "oh I should have thought of fiction, that would’ve been better". But I kept thinking of craft books. There are two that have affected me a lot. I think one is… it’s a book by Lawrence Weschler. He wrote a biography of the visual artist Robert Irwin, who was working in the ‘50s and ‘60s and making these—I’d never heard of him before I read this book—but he was making these big light sculptures and things. It’s a biography, so he interviews him and it’s this whole book that’s a series of interviews and he’s just talking about his practice and his life. It’s just a really interesting book about creativity, and he would talk about how he would go to the studio and sit there and just think, and what that thinking process was like.

I remember when I first started writing fiction, and I was trying to go about it on my own and I hadn’t taken classes yet, what went on in my head was very much like, what do people actually do when they sit down and look at the word doc? What are people doing? I wish I could just sit behind someone and watch how they made sentences or how their thought processes worked. That was something that really frustrated me in the beginning. Because people would workshop, but when you workshop you bring the piece to the class. So I’m like "oh but now I’m seeing the finished thing, I don’t know how you made that. How did you do it? What went through your head? And then how do you revise that?" People talk about revision, what does that mean? Do you go sentence by sentence? When you’re thinking, what’s happening in your brain? That was something that I struggled with a lot in the beginning, and when I read this book—and just a heads up, it doesn’t actually answer the question that I’m asking, I still don’t know—but it’s just a really fascinating look at how an artist goes from having nothing to having something. So I love that book. And it’s called Seeing Is Forgetting the Name of the Thing One Sees by Lawrence Weschler.

And then specifically for fiction, one that I read recently that I loved was Body Work by Melissa Febos. She’s an essayist, and her other book Girlhood which is a series of essays about being an adolescent girl, the sexualisation of young girls and going through that and how that was a traumatic process is really good as well. That was released, I think, last year, and Body Work was released this year. That’s a book on craft; she’s a professor of creative writing and teaches memoir and personal essays.

It’s quite a revolutionary craft book, because she basically talks about how writing—there’s this perspective that writing about the self or autobiographical writing or memoir is frivolous and self-indulgent, and the implication being that it’s less worthy, and not “literature”. She makes the argument that it is, and that it is the most urgent form of literature and that is what people have done throughout history, like various sexism and racism and whatever and everything, has conspired to make us think that this is not important. She’s written this craft book that’s very much about craft and how do you write fiction or how do you write essays while also staying true to that autobiographical urge out of which writing comes, for most people, from the very beginning. It is one, just a very beautifully written book, and two, very wise and I love it. So that’s Body Work by Melissa Febos.

The second question of what I think people should be reading, specific to a Singaporean audience, is Singapore: A Biography By Yu-Mei over here, and Mark Frost, her co-author. It’s an amazing book; it’s really good. I read it in 2017 when I was researching my second novel, which was about land reclamation, and I was like "oh my god, I want to understand all this history, like what’s a good Singapore history book". I randomly Googled it and found it, and it was fascinating, because it was all of this stuff I didn’t know about Singapore. Again, back to the question of, is Singapore mundane? If you read Singapore: A Biography, you will know that Singapore is not mundane. It’s really strange and convoluted and interesting with like drama-filled. And the book covers—I don’t know, Yu-Mei would know this better than I do—I think it starts in the the 1300s and it goes until the 1960s or ‘70s.

I go back to it again and again. Honestly, I’m not just saying this because Yu-Mei’s the host, I literally have it on my desk right now for another project that I’m working on. Even if you’re writing in contemporary Singapore, it’s a really good book to read because it helps you understand how we got here, to that question of how do we live now. There’s all this stuff that I accepted as the way that we live or that this is just how Singapore is, and then you read the history and no, this came out of a very specific historical moment like colonialism or modernism. Or just like the way in which our relationship with China. All of this stuff is really fascinating and interesting. So yeah the book that I wholeheartedly think everybody should read is Singapore: A Biography by Yu-Mei and Mark Frost.

Yu-Mei: Thank you, I didn't expect that! I think that means you’ve probably read the book a lot more recently than I have because I haven’t reread it since we wrote it.

Rachel: Read it yesterday.

Anittha: A book that really helped me think about writing a bit more craft-wise was Shirley Jackson’s most recent short story collection. Her kids found a bunch of stories she didn’t publish and they published it, I think it’s called Just an Ordinary Day. Her short story collections are really cool because some of them are just one page, some of them go on for like half the book. She wrote stories that had different endings in the book. So there would be two of the same stories that start the exact same way and end very differently, and I thought that was really interesting because you don’t really get to see that. Most writers shove that into their bins or into their computers, so that was really cool. I genuinely love her work because she’s so creepy. It’s kinda great to see a woman be so unabashedly creepy, it’s fantastic.

A book from my childhood that really shaped me was the Chrestomanci series by Diana Wynne Jones. That really helped as well because it just gave me license to think differently and be as imaginative as I want and there’ll be people who will read it anyway.

And as for what to read in SingLit, Rachel has really sold Yu-Mei’s book to me, I’m really going to check it out. Because it sounds so interesting, and another book that everyone can pick up is…. (holds up a copy of How We Live Now).

Yu-Mei: Thank you! Yes, I haven’t seen my physical copy yet, so I’m very excited. You should do more show and tell. That’s the book, people. I cannot wait to see it myself. Hold it in my hands the way you all are doing it. Thank you very much! Lots of food for thought about writing and about books to read. I think we will wrap up now. Thank you all out in the audience for giving us your time and attention, thank you to our panellists for your great answers and expanding the conversation, as always, this is great. And thank you to Ethos for holding the whole thing!

🌀

About the Speakers

Anittha Thanabalan’s debut novel, The Lights That Find Us was a finalist for the Epigram Books Fiction Prize Award in 2018. Some of her short stories can be found in Mahogany Journal and Best New Singaporean Short Stories, Volume Five. She spends almost all her free time walking Dino, her poodle.

Jinny Koh is the author of The Gods Will Hear Us Eventually (Ethos Books). Her work can be found in The Iowa Review, Carolina Quarterly and Kyoto Journal, among others. She teaches creative writing at NUS and is the writer and co-founder of editorial firm Deep Narrative.

About the Moderator