"Inclusion has to be about pulling these people who have been historically marginalised from these systems in the processes of remaking them" | Book Launch of Not Without Us : Centring Disability and Inclusion in Singapore

The book launch of Not Without Us took place on 4 February 2023. You can access the full transcript of the programme on this page. Portions of the transcript have been edited for clarity.

SgSL and Speech-to-Text interpretation was provided by Equal Dreams, and made possible through the support of our Ethos Membership Programme. If you found this panel discussion meaningful, please consider joining us as a member, so that we can keep our events and content accessible to all.

--

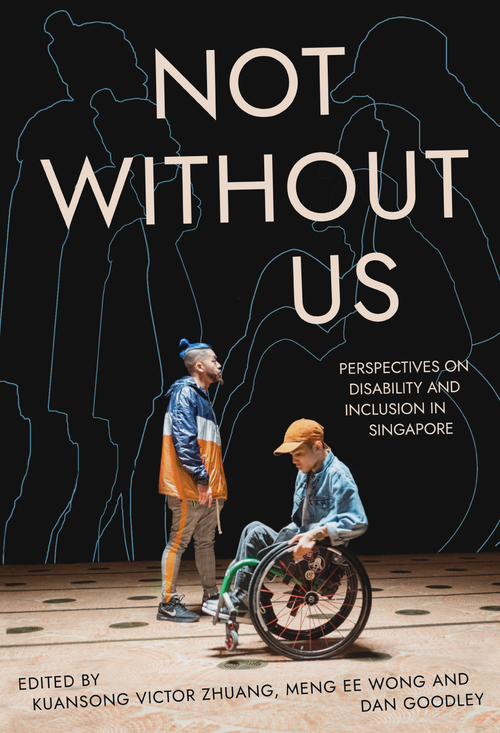

About Not Without Us: Perspectives on Disability and Inclusion in Singapore

Disability is all around us—among people we meet, the media, sports, our own family and friends. Undeniably, all of us have or will one day come to experience or encounter disability. But how can we reckon with the realities of those who live with disability, or its reality in our own lives? In a city-state slowly moving towards inclusion, how do those meant to be 'included' feel about such efforts?

Not Without Us: perspectives on disability and inclusion in Singapore is a groundbreaking collection of essays that takes a creative and critical disability studies approach to centre disability, and rethink the ways in which we research, analyse, think and know about disability in our lives. Across multiple domains and perspectives, the writings in this volume consider what it means to live with disability in a purportedly inclusive and accessible Singapore.

You can find the speaker bios at the bottom of this page. Enjoy the conversation!

Photo of the panelists. Left to right: Alvan Yap, Nurul Fadiah Johari, Jocelyn Tay, Wong Meng Ee (moderator) and joined by Kuansong Victor Zhuang (Zoom).

🙌

Jennifer: Good afternoon everyone, thank you for joining us for the book launch, “Not Without Us: Perspectives on Disability and Inclusion in Singapore.” I am Jennifer from Ethos Books, and my pronouns are she/her. I am wearing a green head scarf, a yellow top, and long black pants. I will be your host for today.

Let me begin by giving my thanks to everyone who made this event possible. To the National Library Board team for hosting us at this amazing venue and for the tech support, to Equal Dreams for providing speech-to-text and sign language interpretation for our guests, and for the editors and contributors. You all are what made this book launch possible.

Meng Ee, the Co-Editor of the book, will be the moderator of our panel today. I am happy to share that Victor Zhuang, another editor of the book, is currently with us on zoom. The 3rd editor of the book, Dan Goodley, unfortunately got a punctured tyre on his way travelling from Ipoh to Penang this morning, so he is not able to join us. I will pass the time to Victor now.

Victor: Thanks Jennifer. Good afternoon everyone. It is actually 1.35am here for me. My name is Victor, I am one of the co-editors of Not Without Us.

So I’m actually in pyjamas, and my hair is a mess, but I am really delighted to be calling in from Princeton to be part of this very important launch.

I will keep my introduction short and use it as a way to thank all the important people who have made this book happen. Firstly, my co-editors Meng Ee and Dan, who have been supportive collaborators and mentors. Dan unfortunately cannot be here with us today, but I know that he would be with us in spirit.

Secondly, all the chapter contributors. You have gracefully given your time and your labour, trusting the editors to do this journey with us. This could not have happened without you.

Thirdly, the team at Ethos, who were not only keen to publish Not Without Us but also believed in us when we first told them about the project close to three years ago, and who put up this very fabulous launch event.

And of course, all of you here at the launch. Thank you for being a part of this! I hope you will enjoy the book and the panel discussion today.

Meng Ee: First thing, good afternoon everyone, welcome to this beautiful set up and opportunity to have this official book launch.

It is really great to be here. I echo Victor for what he had just mentioned, as well as Dan. In any case, I am really excited to be here, to be launching this book. It has been a long time coming. I really want to thank Victor for being one of the key editors who really pulled us all together alongside Dan.

I also want to thank all the contributors. This is the fruits of our labour and I think this sets the foundation for our disability studies.

I am very appreciative and excited that we have so many people step out of their comfort zones. I think, as I read the chapters, I feel that there were many instances of contributors opening up and being vulnerable. I really appreciate that contributors were willing to open up themselves to make this volume possible. I think it is going to be very exciting, where this will lead to. So I am looking forward to that.

I want to also thank Ethos for believing in this project and for supporting us throughout the process. And finally, to all the different team members, in making this session very much accessible to all of our audience.

Jennifer: Thank you to Victor and Meng Ee for the opening remarks. I’m really looking forward to the panel. Meng Ee, over to you and the panel.

Meng Ee: Thank you. Jennifer reminded me earlier that I should give a brief description of myself. I’m wearing a black shirt, and I have got an earpiece in my ear. I use a screen reader, because I’m visually impaired. I cannot see my computer, so I rely on a screen reader to be reading to me.

To turn your attention to our three panelists, perhaps a good starting point would be to invite each of you to give us a summary of the chapter you’ve contributed to, and what inspired you to write that. Perhaps I can invite Jocelyn to kick us off.

Jocelyn: Thank you, Meng Ee. I will give a brief description of myself as well. I’m wearing a dark blue blazer over a dark grey shirt.

With regards to my chapter, it is a discussion about the experience of meritocracy in Singapore, from the perspective of neurodivergence. It’s based on the precedent of how we constructed our image of society and the people living in it, as well as the unfortunate biases that are built into the systems we experience.

It examines the intersection of class, disability, and neurodivergence that occurs within the systems of meritocracy. It is the repudiation of the concept that any person, regardless of disability or class, should be stripped down to their value in capital and what the rights afforded to them based that value.

This chapter was inspired by my experiences as an autistic, neurodivergent student. I acknowledge my position is one of privilege. I was lucky enough to receive therapy. And lucky enough that I appeared smart enough to fit into the technocratic mould. Yet those things didn’t really give immunity to the underlying issues of surviving the Singaporean education system. I still got bullied for stimming, in my case chewing my pens. One of my teachers did intervene and provided support – I always felt that these conditions were conditional on success. And not just any success, mind you, but following a neurotypical model of success. Modelling myself as tolerable to the wider society in spite of my eccentricities.

“Masking” in this way, as any neurodivergent person can tell you, is exhausting. It’s like trying to put on a perfectly scripted performance, a mask placed so perfectly that it could be mistaken for your face. It’s stuffing all your sensory issues under a lid. All the pain and irritation is just bottled up until you get home and collapse. It eats at you. The most damning part of it all – and what I was tricked into believing for a long time – was the lie that suffering was my fault.

Meritocracy sells the idea that you’re responsible for yourself. That the only thing limiting you is your hard work. To build on, and sell your talents. If you fail, it’s not because you were pushed beyond any reasonable limit. It’s because you clearly didn't work hard enough.

It completely paints over the idea that some people don’t fit into the standard conceptions of merit. Or will trip over institutional stumbling blocks.

I loathed myself for a long time because I thought if I failed even once, I would have no place. I wrote this chapter in response to those experiences of pain. I wrote it to put a spotlight on the root of the problem, the systemic attempt to put an economic value on people, making their dignity as a person contingent on how well they can dance for a non-disabled neurotypical society.

I know that because of my position of privilege, I don't experience the intersections between economic class and neurodivergence, that exists at the core of meritocracy as an issue. However, I still believe it is important to point out that intersection for other neurodivergent people, so that we might consider a more inclusive society.

Meng Ee: Thank you very much Jocelyn, I must say your chapter does resound a lot with me because of my interest in the topic, but we will dive a little bit more into it afterwards.

Maybe I can ask the same question about what inspired you, Fadiah, with your chapter.

Fadiah: Thank you, Meng Ee. I’m wearing a silver headscarf, silver dress and beige pants. The journey into writing this chapter began a few years ago – in 2017-2018. I was really trying to make sense and make meaning. Mental health is one challenge, but it is also my experiences accessing psychiatry as a service user.

I was trying to make sense of why I was experiencing a lot of difficult emotions while getting help. You know, supposedly, I was trying to get help, trying to get better. So I wrote an earlier piece in a Pause journal in 2018. After a few years, this chapter came out as a way to go further in this meaning-making journey.

My chapter tries to critically address some of the dominant narratives in contemporary mental health discourse. I wanted to question the dominant ideas of recovery, which I personally see as a way of gaining alignment to mainstream neoliberal capitalist society. And how the idea of recovery is often pushed as an individual responsibility. So if you’re someone with mental health issues, you are supposed to go for treatment, you are supposed to get help, and you need to get better.

The narrative is always about trying to recover. I wanted to question a bit more about what recovery meant, based on my own personal experience and reflection. And I feel a lot of these narratives that we see out there, that are pushed out there, do not regard how social context, structures, and ideologies also have a crucial role in perpetuating mental illness.

Instead, what we get when we talk about mental health issues is often the language of disease and pathology. And this is widespread. Mental illness is always being equated as a disease, and therefore we need to seek treatment and then recover, as though recovery is kind of linear process. What I believe, as someone who has been trying to ‘get better,’ is that it is not so linear, it is actually very complex.

I wanted to explore a bit more of that based on my experiences as a psychiatric service user. And question some of the institutional assumptions about mental health and recovery. I also feel that the current efforts to boost mental health are important, but at the same time, it takes power away from people who are actually struggling and from service users themselves.

The first part of this piece tries to examine some of these dominant narratives. The second part is a call for change by advocating for more ground-up and community-based approaches towards mental healthcare, beyond institutionalised forms of care. That was why I shared about my experiences in peer support spaces.

I feel that community and support spaces are very important as a way to address some of the gaps in the current systems we have for mental health. It shifts the power of narrative-building back to the service users as they themselves seek to define what mental health means to them. I think the narratives and insights of psychiatric users are important as part of our collective knowledge-building about mental health, and to foster inclusivity beyond the dictates of professionals.

Photo of the panelists, with Fadiah Johari speaking

Meng Ee: I must say that before reading your chapter, I had little insights into mental health and you brought a really refreshing perspective on that. I look forward to learning more and for us to grow in that space.

Alvan, can I turn to you next to share a bit more on what inspired you in writing your chapter? Can you also give us a summary of your chapter?

Alvan: This is Alvan speaking. I have short hair, I wear glasses and hearing aids. I have on a grey tee, a denim jacket and red shoes.

I have had the privilege of being involved in the performing arts and theatre sphere for a couple of years. Before that I was working as an editor and writer for a publishing house, which happened to be Ethos Books, so I am looking at some of my former colleagues here.

What inspired me to write my chapter, to be frank, is the co-editor Victor Zhuang chasing me for quite some time to contribute something!

It was because of my past experience and participation in the performing arts. I was a playwright for a play on special education which has direct links to the disability community, as well as being the so-called first fully accessible play in Singapore. So I felt it was timely to share my experiences and what I learnt, as well as my observations of the disability art scene in Singapore.

The title of my chapter is “And suddenly we appear” - a play on the words of the title of another play which was the first disability-led production in Singapore

From the title alone, there is a hint of what we are trying to convey. And suddenly we appear — is that so?

I was giving some background and context on how disability arts here in Singapore has developed. Its beginnings, what is happening now, and my hopes for the future, for its development and further growth. That is basically what my chapter is about.

Meng Ee: Thank you Alvan for giving us a brief look into your chapter, and how the disability art scene might be moving in the future. Now I want to move onto the next question. I think one of the main objectives of the book Not Without Us is to move away from how disability is understood as primarily charity-based and medical-based. To move into a space where we can see how disability can be understood. What I have is a geriatric source of knowledge and embodiment.

Without going into too much description, I think a simple way to understand that is: How has disability become a source of strength and empowerment through your writing and through your experiences?

So perhaps, through your own experience growing up and living with disability, how have you seen your own experience shift and change from seeing disability as we would normally see it? How has that journey been for you, and how has being involved with this writing, spending time reflecting and making meaning of your own personal experience, been?

May I start with Alvan first for this next question?

Alvan: I grew up in the '80s and '90s, which was 30 - 40 years ago. At that time disability was very much a stigma. Very much invisible. I mean, really invisible. Even wheelchair users, who are very visible, can hardly be seen in public. Very much less for the so-called invisible disabilities like autism, mental health issues, and deafness.

So from then until now, of course there have been a lot of changes, a lot of improvements. Nowadays you can see wheelchair users everywhere, even on public transportations. We have much more knowledge about disabilities like autism, deafness, visual impairment, and intellectual disabilities. The publicity is out there, there are campaigns, there are schemes.

So, in that sense I think attitudes have improved, people are now more accepting. More open. But, I think on a scale of 1 to 10, 1 being terrible and 10 being very good - back then during my time, 30 or 40 years ago, it had been a 1 or 2. Now, maybe it is a 4 or 5. There is an improvement, but there is still a long way to go.

There are so many barriers and misconceptions of people with disabilities among the general public. Even when you have a family member who has a disability, you don’t really engage or understand it that well because the stigma is still there

As for how this, and my disability, has impacted my own input, my own writing, and my own public speaking, I would say that I am a very average person. I was always very unwilling and very afraid to speak up or speak out. One factor was, back then, so little awareness or knowledge of disabilities in general, even for myself. I was the only student with hearing loss in primary school - or so I thought. Until many years later I met someone in the Deaf community and she told me: I was also in that school! I was two years your senior! There were no opportunities to get to know people who have the same conditions as you, especially if it’s an invisible disability.

As I grew older and found more opportunities to be exposed to a larger world, I met more people in the Deaf community who have similar experiences as me. So I slowly started to find my voice. In other words, I ask myself, If I can, If I am able to, why not? In terms of raising awareness and talking about my own Deafness. I’m sure Jocelyn and Fadiah would tell you that having a disability is not easy. Growing up, all the barriers you face. It takes a certain degree of courage to share openly and tell others about these difficulties you face. Of course there is always an element of shame. You are not normal. We are not part of mainstream society.

In a sense, I feel like having the ability to express ourselves through our writing or other means, is something that, because of my own background experiences, spurred me to do something more.

Meng Ee: Thanks, Alvan. So, similarly, can I also ask Fadiah to share a little bit of how writing the chapter and reflecting on your own journey have changed things for you?

Fadiah: Looking back, I internalised a lot of the negative stigmas surrounding mental health and help-seeking. I didn’t quite take mental health so seriously when I was younger. The environment I was in was not very supportive or understanding of mental health struggles. So oftentimes, mental health is dismissed, you are thinking too much, you are too sensitive, just be strong, you know?

I think even when I first had my onset, my first episode in 2014, it was really hard for me to accept that I was unwell or ill. I was hospitalised without my consent because I was not in a state to give consent. I was not in a functioning state of mind. I was not able to eat or sleep or drink. I share in my chapter that I was restrained, which is something I am very against. Because I don't think anyone should be restrained when they are going through intense mental distress.

When I was told I was ill, I didn’t agree. I felt that I was going through a very intense emotional and spiritual upheaval, but it wasn’t really a kind of illness. I didn't think I was a sick person. And then when I said I am not ill, the doctors told me I was confused. I think that kicked me into this journey of like okay, why do I feel this way about myself?

Other people were telling me that I am sick and my whole family was telling me that I am sick. I realised later, after many, many months, several years of thinking about the condition - that maybe illness is just a description of someone going through distress. Maybe illness is not within myself but it is also within my environment, which includes the social environment, or the things I was doing, or things that happened to me.

It took me a while to realise that maybe I had some issues with trauma, which is why I had breakdown issues in the past few years. Only after seeking treatment did I start being more open with talking about my personal struggles. Writing has been the process which had made meaning out of this experience. Never once did I pathologise or treat my condition as a kind of disease. It is a struggle, but it is also a condition that I live with. It is not a disease.

I speak quite strongly against treating people’s very legitimate struggles of madness as a kind of disease. I do believe that historically and culturally, madness is seen as a normal human condition, as a manifestation of trauma or stress. So I’m hoping that in this experience of writing, other people can feel comfortable to talk or write about their own experiences as well, especially how they feel internally. It may not necessarily agree with what the professionals are saying.

Meng Ee: Thank you Fadiah, I think a lot is to be learned from your experiences.

I shall turn over the time to Jocelyn to share a bit on how disability has been a source of strength and knowledge for you.

Photo of the panelists, with Jocelyn Tay speaking

Jocelyn: Thank you Meng Ee. I talked a bit earlier about my experiences of being autistic. When I was younger, I experienced a lot of ostracisation. I have distinct memories of being bullied by my classmates in primary school, having my property thrown away, or even my thumb twisted when I bit my nails. Even after getting a proper diagnosis, the relationship between bullying and my autism didn’t register. I thought getting picked on was a part of life. It wasn’t until I grew older that I realised that there was a lack of proper information distributed about autistic students.

What I experienced was a form of ableism. And well, today I appear to experience the opposite. When I explain that I am autistic, one of the most common things I hear is that I don’t “look autistic.” Which feels patronising, as if autism is something that is visually alien, and what I experienced doesn’t exist because it is not autistic enough.

It might be the fact that I am now a university student. It might be because I am neurodivergent in “acceptable” ways. It is still an attitude that considers neurodivergence as separate and alien, or accepted on an exclusive basis. I think it is that experience of ableism that influences my writing and made me aware of these structural problems.

In terms of my experience of disability as a source of knowledge, I could offer a different perspective as an autistic person. I do things a little differently and it does provide me with new ways of looking at my work. There are creative solutions, and different ways of looking at sources to write and create things that wouldn’t be possible otherwise.

Unfortunately, this in conjunction with the experience of ableism also makes me aware of the sources of knowledge that are delegitimised or deprioritised when sourced from those with experiences of disability, even when they are so important and useful in many ways.

If I could share a personal anecdote in the process of actually writing this book, I wanted to conduct oral interviews with other neurodivergent people as part of this project to get a sense of how other people experience these institutions and the solutions they come up with. When I brought the idea up to my ethics board, the recommendation they provided to me was to obtain consent not only from the neurodivergent people themselves but from their parents and guardians. I should note that the neurodivergent people that I wanted to talk to were 21 years and older. A bunch of consenting neurodivergent adults are treated like children on a field trip by academia, can you believe it?

I felt like that was a highly infantialising perspective, and it's one of those things that made me particularly aware of this form of institutionalised ableism. That kind of deprioritizes disability as a source of knowledge. I still believe that disability – in the sort of creative way which provides unique perspectives and diverse solutions - is valuable and should be considered a legitimate source of knowledge. Which is why I think there needs to be a greater priority for disabled people speaking out.

Meng Ee: Thank you Jocelyn. You raised a really interesting point about seeking consent. In this case, you were talking about how neurodivergent individuals have to get consent from their parents to participate in the interviews. Those of us who have had the unfortunate experience of dealing with IRBs and ethic boards will know how challenging these boards can be. The intention of these ethics boards is to protect the vulnerable population, but you raised an interesting point here. There are certain populations quite able to make those decisions for themselves, so perhaps this is something that IRB boards would need to grow towards in time. Thank you for sharing that.

I want to dive a little deeper into the chapters that have been written. Just to get a little bit more in-depth with the writings. If I can just start with Alvan — I think your chapter makes a distinction between disability-led art by practitioners, as opposed to what mainstream art is trying to advocate for – and that is greater inclusivity and accessibility. Can I get you, Alvan, to share in what that difference might be?

Alvan: First of all, I wish to say that I don’t really distinguish between mainstream arts and disability art. To me, art is art. So what exactly are we talking about when we talk about disability art? Very simple, this is art, created by disabled artists or led by disabled artists.

The key issue here is, when you talk about disability arts, what is your reaction or perception?

Maybe you're thinking, "is there such a thing?" Or you think of shelter workshops. Or of disabled people making arts and crafts, or art therapy, or rehab services which involve the arts. But, in my essay, I am referring more to the fact that there are disabled people out there making art. Whether it is literature, stage production, musicals, plays, whether it is performing arts like singing, acting or other forms of art. In other words, it is exactly the same as mainstream art. What you see in exhibitions, and what you see in productions by major theatre companies. But of course this is a bit more rare. Right?

First of all, there is this perception that there is a limited number of roles disabled people can play. For example, on TV or in the theatre. If you are a wheelchair user, and there is a role for you on TV, it must be the role of a wheelchair user, right? There will be people who think that if a character is a wheelchair user, there has to be a backstory to explain why this character is in a wheelchair. It's additional work! But I think, why do we even need to explain the backstory? This person, this mother or uncle or child, is in a wheelchair, fullstop. Then you continue the main plot of the story. Just give a disabled person who is involved in, or who makes a living through the arts, the opportunity to be cast, regardless of their disability. Judge them for their skills and talents.

The other aspect is, of course, the fact that there are disability productions directly inspired by their artist's disabilities. Maybe it's not even their life stories, but stories based on their disability or something that is in some ways related to their disability.

I think we all have watched movies in which the main characters have a disability, and the entire plot is focused on the fact that, oh this person is blind, oh this person has a physical disability. I think there are some famous examples. Rainman, My Left Foot? Hollywood movies.

These are movies that were given Oscars. But of course, the issue with all these productions is that the disabled roles were played by non-disabled people. The scriptwriters, directors, everyone involved is non-disabled. In terms of disability arts, what comes to mind is, why not have such stories told or produced or acted on directly by the people who know these stories best? The disabled artists, the disabled scriptwriters, the disabled producers themselves.

Disability arts is made up of a wide spectrum. It can be something like "my disability is irrelevant — I want to be a performer, I want to be a writer." Or it can be "my disability can be directly relevant to my play, my book, or my musical. It’s inspired by all these – my lived experience as a disabled person." That is also disability art.

When you come to that, do you think there is a difference between disability art and mainstream art? I don’t think so. Because mainstream art is also inspired by lived experiences. They have their own struggles and issues as well. Some of them bring that to their stage, to the screen, in their writing, in their dance production, and so on and so forth.

It’s the same. Maybe not exactly the same but it is similar. For me, there is no real distinction. Art is Art. But of course, for disabled artists, we face a tougher, and longer, and a more challenging obstacle course to get our foot in the door in the first place. In terms of finding opportunities and even the fact that general mainstream society doesn’t give us much of a chance. It is only recently that you get to see more and more disabled people up in movies, on TV, and so on. Because of more awareness and more opportunities. We still have a long way to go, and that is my take on the issue.

Meng Ee: Thank you Alvan. Actually, when you were talking about building a background story to explain, I fully agree with you. When you were talking about able-bodied actors playing disabled persons, the one movie that came to my mind was Scent of a Woman. Al Pacino, famous actor. Played a blind person. And I think what you were saying is, why can’t we find a blind actor to do that?

If I take that a little bit before, for those of you who were young enough to remember, Charlie Chan. Charlie Chan, who is supposed to be a Chinese police detective. I think it was quite a popular TV series in the '70s. It was an American series. He is supposed to be Chinese, but he was played by an American, a white American. So of course they did a lot of heavy makeup and so on. Related to that, Bruce Lee, a famous martial arts artist trying to break into the Hollywood scene, not wanting to compromise himself as a genuinely legitimate Chinese actor, felt that he had a place in Hollywood. And of course he left a legacy for others and for people to stand on his shoulders.

If I can move on to Fadiah now, for your chapter. You talked a bit on how mental health is often pushed onto the individual. They have to somehow deal with that almost singularly. But I think you are presenting a different perspective. In the sense that, maybe some of these issues that drive people, or places pressure on mental health, could be a result of neoliberals, capitalists, and other soft forms of oppressions. Can you share a little bit of your ideas on how these different systemic factors contribute to the mental health experience of individual patients? How could we better frame it to create more opportunities for greater understanding between health practitioners and individuals with mental health issues?

Fadiah: I mean, as we see now, the kind of dominant narratives that we get surrounding mental health often reduces mental health to a personal and individual struggle, rather than something that is experienced at the collective level. Even though we know that, for instance, in Singapore we have a lot youths struggling with depression and anxiety, we don't talk about it as something to do with the way our society is functioning. Some problems are inherent in our society, but we talk about it as if it is our personal struggle. It is personal on one level, but it is beyond personal as well. I wanted to talk about that in my piece.

Oftentimes mental health struggles are taken out of context, so we do not understand why people face anxiety. For example, when I talk about structural problems, it’s really the day-to-day struggles that people face, stemming from, for example, socioeconomic issues like poverty, or from people facing racism.

When we talk, for example, about loneliness as being one of the key factors causing depression, we don't talk about loneliness as a structural or societal issue; we talk about loneliness simply as a psycho-emotional issue. When actually, the conditions of loneliness itself shows the conditions of the society that we are entrenched in.

For people who are low-wage workers or people dealing with poverty and job insecurity, they are more likely to experience depression and anxiety because of the precarity of the life that they live.

Simply telling them that oh, they need to get help, you need to go to get treatment and therapy, is not going to change the actual lived conditions that they are facing. What I’m saying is that while it is important to get help and therapy, it is also important to, when we speak about mental health, go beyond just that. I want to see more discussion on mental health that are rooted in the lived realities and structural conditions of our society.

We talk about Singapore as a very neo-liberal society, which means that we are a very competitive and individualistic society. What are its repercussions on our education system? How does this cause stress among students and young people? How does this create a sense of loneliness and isolation? And the depression and anxiety that comes with it?

We live in a society that is very intolerant and punitive of mistakes and failures. There is a lot of pressure for young people to do well in school. We hear stories of even primary school children being suicidal, and some of them acting out on it. These are very legitimate concerns and it is something that needs to be addressed at a societal level, rather than just the individual level.

What I hope is that when we talk about mental health, it becomes more of a collective issue. Therefore, the kind of solutions or ways of addressing or supporting people with mental health becomes more communal and societal rather than just individual.

Meng Ee: Thank you. Just on the issue of exams and competitiveness in Singapore, I think many parents and students would very much align with your call for that concern.

Jocelyn, if I can turn to you now, you talked in your chapter about media representation of neurodivergent individuals having to conform to ableist images and profiles. Can you share a little about why this might be troubling and how we can frame neurodivergent perspectives better?

Jocelyn: So the core reason why these ideas are limiting is that they reduce neurodivergent people, and really any person, down to what they can contribute. It creates two boxes of people – those who produce capital, and are therefore productive, and those who do not and are therefore a burden.

In a manner, that is very similar to the functional labels. I’m sure you have heard of high-functioning autism and low-functioning autism, severe autism, so on and so forth. It suggests a certain hierarchy of disability — and the rights of the individual are contingent on where they are on this hierarchy.

The fact that these ideas of productivity are based on neurotypicality further limits the potential of neurodivergent people by ignoring alternative modes of expression and the diversity of experiences that we have to offer. Any disabled person, and any neurodivergent person, should be allowed to express their views as adults and people first without needing to prove themselves with half a dozen degrees, a resume and looking normal enough.

What I believe is needed in this system is more neurodivergent voices that clearly represent their perspective, and for our experiences to be respected. It really is quite simple, allowing the person with the experience to talk about themselves, even if it is something as simple as respecting our choice of language. I would not have to fight over being referred to as autistic rather than a person with autism. And while caretakers and families are very useful allies in advocating for neurodivergent rights and neurodivergent perspectives in the system, they should not be superseding the voices of the neurodivergent people themselves.

With this regard I encourage neurodivergent people to write and talk about their perspective on the world so that we may be understood as people and not as human resources.

I will acknowledge that not every neurodivergent person may be in a position to do so. They might not be comfortable identifying openly due to the possibility of jeopardising employment or educational prospects.

Discrimination due to one’s neurodivergence is still something that happens today. Which makes the act of speaking up that much more important, to call out such systemic discrimination and the diversity it excludes.

In this regard, talking about neurodivergent self advocacy, I want to highlight some of the work of other autistics, such as Wesley Loh. He’s spoken up about the need for explicit legislative protections for autistics and neurodivergent people in areas such as healthcare, insurance and employment. A bulk of our society is still in the process of including a more diverse range of neurodivergent perspectives on a more fundamental level. These self advocacy movements should be important and should be promoted. They fought neurodivergent rights on neurodivergent terms. And while we still need to renegotiate the system to remove these kinds of ableist tendencies, these people who kind of speak the language and kind of "play the game" are needed to ensure protections and rights for people who live in it. And if we have to play the game, we might as well be represented by ourselves.

Meng Ee: Thank you Jocelyn. We are running a little bit out of time, so I think it may be nice to pose a final question to the panelists.

Just to understand, what more can be done, in your respective areas that you have covered? If I can just pose the question to Alvan first, what do you anticipate and hope for a more inclusive arts in Singapore?

Alvan: Okay, briefly, I would like to see more opportunities — more funding, more programmes for disabled people to actually participate in the arts beyond those therapy or rehab kind of structure. And I also hope that the public, the community at large, will be more receptive towards disabled artists and disability-led productions.

It would also be good if we get more publicity, to garner greater awareness as well. But I will say here that at this point, I’m actually very thankful that we have quite a number of mainstream arts organisations, theatre companies, and even art institutions being very supportive, ensuring that productions are now more accessible and inclusive. This is an important first step. You would not expect disabled people to suddenly develop an interest in the arts if they never had the opportunity to attend the play in the first place, for example.

For the first step, you need more access – discounted tickets, accessible productions with captioning, audio descriptions, so on and so forth. So that is my wish.

Meng Ee: Thank you Alvan. Fadiah, in your chapter, you talked a little bit about peer support circles for individuals with mental health issues. So that they are able to come together and be given that space to discuss their issues and be affirmed. Can you elaborate on how this can be scaled up to psychiatric services in the community?

Fadiah: I think peer support spaces function as a way to empower service users to develop their own narratives and make sense of their own experiences.

Another level of advocacy is to call for the availability of better forms of care and services. Peer support spaces tend to be very closed and private. But people from these spaces can advocate. It could be online or through talking to their own doctors. To say that "hey– I want – I would like to see more of a certain kind of approach towards mental health care". I think this should be done collectively rather than by individual service users.

For example, I mentioned in my chapter that one area of concern faced by people from minority ethnic groups is racism - how that has repercussions on their mental health as well. Talking about this and raising awareness to professionals would mean that professionals would also then need to develop a keener lens or a sensitivity towards racism, to know how they can better support people from minority communities in dealing with racism as part of their mental health healing.

It could be racism, it could be other forms of discrimination, it could be sexism, it could be homophobia, and so on and so forth. So I think it is important for psychiatric services to allow for marginalised groups to voice out on these issues and articulate the changes that they want to see. I think that might help.

Meng Ee: Thank you Fadiah.

And finally, to Jocelyn. And this is a big ask here, how can we have a disability-inclusive meritocratic Singapore? Is that possible or is ableism, meritocracy and neurodivergence all too intertwined and too difficult to disentangle for our society?

Jocelyn: I think in regards to that question, there are some fundamental problems with meritocracy. Like I outlined earlier, the main problem with meritocracy is that no matter which way you try and slice it, it attempts to ascribe a quantifiable value to a human being.

Now in its best case, and this is the narrative expounded a lot in Singapore's society, is the idea of a “compassionate meritocracy.” The idea is that those who are better assists those who are not. Yet such a line of logic suggests that some people are worth less, be it for their neurodivergence, their disability, or simply for not conforming to standards of merit. It can be patronising and it does not afford dignity to those who receive that kind of assistance.

At meritocracy’s worst, we see the snarl of neoliberal logic that suggests stripping rights away from those who are worth less, such as dismantling welfare support systems for those who do not conform. This all goes back to the logic of making people ideal to feed into the engines of society rather than asking what a society can do for the people who live in it.

I believe that in this regard, we should stop considering meritocracy as an untouchable ideal. People shouldn’t have to ‘prove’ their right to exist by any metric. I believe that it might be best to work from the premise that all people are inherently valuable and are capable of various modes of contribution and move forward from there. Work towards addressing the needs of the people first, then allow them to work in their own way. Prosperity and success does not have to be a zero sum game like meritocracy suggests, and it would be better for us to work together rather than against each other in the creation of such a society.

Meng Ee: Thank you Jocelyn. Those are big issues, and very weighty issues for us to ponder over and to see how we can move forward. I think because of time, and because we want to allow some time for questions from the audience, we will stop the panel discussion at this point and open the opportunity for questions from the floor.

Jennifer: Before that, we can thank our panelists for the sharing and discussion. Thank you so much! I have one question here which I would like Victor and Meng Ee to answer first.

What was the most challenging thing about curating the chapters into a cohesive edited collection?

Victor: I will start first by sharing that I think ultimately for us, when the contributors came in, with the abstracts and the first drafts of the chapters, it did not really feel that hard for the form of the book to take place. What you see in the book, the three sections, are art and culture, policy orientation and intersection, as well as disabled lived experiences. I think it naturally coalesces into those three categories. They sort of speak for themselves. So it just happened that it fell into place.

I think for me and Meng Ee, and of course with Dan as well, we've always been in a sense, partners-in-crime — I hope we can call it something like that. We’ve always been talking about the possibility of creating space for disability studies, to think more critically around the condition of disability, around the disabled experience, having scholarships that centre on disability, treating disability as not simply the subject or object of study, but rather as the generative source of knowledge.

And I think that’s what we hope to achieve with this book. Hopefully, this book will begin a new wave of scholarly work, of research, of both academic thinking, as well as public discourse about how we can think around disability and inclusion.

Meng Ee: I think Victor is absolutely right. We had a good steady stream of contributors come in and as the chapters come in, we had a good problem on our hands in the sense that we had quite a number of chapters to select from. In terms of difficulties, I think we had to make a decision, which ones we would ultimately put into the volume. And maybe I’m just leapfrogging a little bit ahead, but perhaps this is an indication that there may be a next book that might come in the time ahead. Because there is definitely a lot of capable individuals out there with experiences. They want to write and share and talk about it.

Victor’s talked a little bit about what we envisaged with the book. Just serendipitously, Professor Paul Tan just talked to me and asked whether we have disability studies in Singapore. We don’t have that yet but perhaps this is a foundation that may lead to it. Who knows? This could lead to an opportunity for us to look into this with a bit more depth. There is an interest in this field and maybe we should start looking at it, deepen it, and maybe make it a course of study so as to formalise it. Because I think at the moment, I am embedding disability studies as part of my teaching, and in special education, inclusive education and so on. Perhaps in time there could be an opportunity for this to be deepened in that space.

Jennifer: Thank you Victor and Meng Ee. So I think the next most popular question, for the whole panel is:

What challenges may be restricting this push to disability leadership or equal representation of disabled individuals? And how do you feel about the role of government?

Jocelyn: I believe I can start first in this regard.

I think one of the main issues preventing equal representation, at least when it comes to neurodivergent advocacy, is having an equal share of voices. The problem with neurodivergent advocacy, particularly autistic advocacy, is that for the most part, there isn't really a particular leadership.

For a lot of disability movements, you can’t really pin a particular leader to these movements, mostly as a result of a lack of education and a lack of support for disabled people being presented as leaders. For a long time, it was believed that disabled people could not lead. As a result, it fit us into a feedback loop where, now that we are attempting to try and make our voices heart, there are not many people who are trained to lead these movements.

On top of that, at least when it comes to the autistic movement, our movements are quite disparate. Our needs are very different and as a result we do not have a particular monolithic community, which would reduce our social leverage.

I’m not saying that a monolithic community is the correct way to go about it. In fact, the diversity of the community is part of its strength. But there needs to be a greater share of voices in order to obtain this equal representation. On top of that, when it comes to the problem of media representation, there’s also a persistent problem of being misconstrued.

Media institutions are fundamentally non-disabled and neurotypical, and as a result, there is a frequent misunderstanding of our issues. A common thing I heard is that, advocates get frustrated with the slow pace of change as well as the way people are represented in newspapers and interviews.

With regards to the role of the government, I believe that part of this thing is to enable collaboration. One of the main ways that advocacy occurs is through lobbying, through this collaboration with state and organisational actors. And I think that this collaboration needs to occur on an equal standard.

Neurodivergent people and disabled people shouldn't really be considered a tokenistic inclusion. They should be the focus and a kind of respected contributor in these particular collaborations. I think that’s actually an important part of increasing the legitimacy of disability representation in the current state of society.

Jennifer: Thank you Jocelyn. Anyone else want to add on?

Alvan: I’d like to add on, maybe follow up on what Jocelyn mentioned. I think one reason, that is my assumption and perception lah, why organisations and the governments may hesitate to truly include us and give us equal representation, may be because of a vested interest factor. You are directly involved - you are directly interested in this area. So, can you be neutral, can you be impartial? Can you make rational decisions without letting your emotions overwhelm you? Things like that.

There are worries you know – because "oh, I have a direct stake in this, so I cannot be fair, I cannot be neutral". Looking at objective facts and evidence, and making decisions according to that, I let my emotions, my personal interest overcome that. That may be one of the perceptions from the organisations and authorities. As to how to overcome that, I have no good answers, but everybody has some kind of personal interest and stake in anything we do, right? So that's why they treat us differently.

After all, we know best and we are the experts in this particular area. So I hope for more than just pulling us in for feedback and consultation sessions. It is not enough. We need to have a seat at the table in terms of making policies which affect us. We have to have a say. And not just someone else who records our words and send it upstairs, to some black hole, or some black bus.

Fadiah: I also have a point to make, in relation to what has already been shared, which I agree very much with. With regards to the issue of representation, the idea is who has authoritative knowledge to speak on these issues, right? And oftentimes, if we talk about the government, they are always giving a lot of power to the institutions and professionals trained in the field, and not so much at the service users or people with disabilities themselves as experts of their own experiences and equals in terms of knowledge production.

So, if we can move towards shifting power back to the people with disabilities as well as service users, then we may make a step forward. If not, it is still a very top down kind of approach.

Meng Ee: Thank you. Maybe the title of book here comes again to light and attention. Not Without Us, right? And I think that really sends the message that it is about disabled persons. Any policies that the government makes, it is very important that disabled people are there. As Alvan said, at the table, not just through proxies or through studies and so forth. I think it really is about involving disabled persons throughout the whole gambit of how society operates.

I think there’s a lot of representation in social policies, welfare-related programmes, but maybe that is a little bit lacking in the other aspects of the whole operations of society, of nation building.

That also means, we need a lot of you, the disabled persons, to be involved, to continue advocacy work and to be engaged and to be part of that landscape.

It kind of points us back again to the importance of bringing this whole discussion into the foreground. And how all the issues we talked about, and more in the book. How can these issues be brought into the current debate and discussions?

So I think, for the government to have a greater listening ear, and for the community of disabled persons to also be seeking greater engagement from the government.

Jennifer: Maybe we can take one question from someone in the audience if you’re keen to ask. Anyone keen to ask a question?

Noah: Hello, my name is Noah. My question is, what does publishing this book mean to you?

Jocelyn: I’d say that in terms of putting forth my contributions in this book, it’s my first time trying to advocate for disability rights. I actually haven’t really been engaged with advocacy prior to this. But then I threw myself headfirst into disability studies, learning about these various kinds of issues, and looking at my experiences in a new light.

What publishing this book means to me is that it becomes a kind of legitimisation of my experiences, of the kind of work that I’ve done, and the potential for so much more. Both in advocacy and the area of academics.

Fadiah: I think publishing this book has been very meaningful. Personally because, it’s very difficult for me to get my thoughts out there because it seems like I’m going against the grain and what the doctors say.

Thanks to affirmation from the editors, it’s coming to fruition and I am able to put myself out there, and have people listen to me. It's actually quite nice.

Alvan: It’s the chance for us to tell our stories, to share our experiences. I think anybody here would have this feeling, of wanting to tell people how we feel, what is happening, and what we can all do together. Tell the world, that we exist and this is us, and this is what we stand for.

Meng Ee: Disability has a lot of diversity, but I think in that diversity there are quite a number common themes that surfaces. And it is creating a space to express those challenges that we have experienced. Reading the essays have been quite invigorating for those of us who understand those personal journeys of having been misunderstood in our youth, mistreated in our youth, discriminated, and so forth. And somewhere along our journey we have reengaged the regenerative source of knowledge and embodiment. Instead of disability being the source of despair, it can be empowering.

Jennifer: We have time for one more question. We will pass it to the person in the audience. So this is the last question.

Audience: Thank you. I really enjoyed your comments. A lot of the things that Fadiah and Jocelyn pointed out, the fruits of your analysis and reflection, seems to indicate that a lot of concerns for communities with disabilities seems to have something to do with capitalism, meritocracy, neo-liberalism, and these broad conditions that we live in. What I'm curious to hear from you is what is your imagination, and what are your commitments, in terms of what it looks like, to transform these systems.

Because disability, just like activism in other contexts, have often talked about how accessibility is not justice. Because we don’t just want access to horribly unequal systems, to participate a little bit more in a system that ultimately does not serve a lot of us. And that disability justice is more than, say, for example, the inclusion of students with disabilities in the current education system. But, Fadiah, like you pointed out, so much of the current education system that exists does not serve all students because it is punitive, and because it undermines our sense of self and worth and all of those things. So can experiences of disability then be a root to our politicisation, and the ways in which we seek changes that don’t just benefit – or aren’t just framed as things that benefit people with disabilities within existing systems, but seek to transform systems that benefit and liberate all of us?

For me, as someone with neurodivergence, it informs a lot of my political work. So, I’m curious to hear your thoughts on how you see connections between the ways that systems of psychiatry restrain or incarcerate people in carceral systems, and how they in fact have an overrepresentation of people with disabilities too, and the many ways that carceral logics that oppress people with disabilities also oppress so many other communities. So then what does it mean to say that you’re an activist or person with disability fighting for these issues versus fighting for a more cohesive kind of forms of liberation?

Jocelyn: Thank you for your question. I do think there is lot of intersectionality between the issues of disability and neurodivergence, and all these other issues. As I’ve pointed out, say - there is class and neurodivergence, and there’s race and mental health issues. These institutions fundamentally misunderstand the problem, they don’t take into account these kind of operations that are baked into the system.

In that regard the advocacy and change does reach down to quite a deep level. We need to reassess what we think an ideal society is. For example, when I put forth my critique of meritocracy, I think we’ve gone beyond saying that we want to aspire to be a “truly meritocratic” society. Maybe meritocracy is not the best idea to begin with. And I think this goes towards a good number of these ideas, that come from, say, non-disabled and privileged ways of thinking.

For example, the idea of the strong helping the weak - implies fundamentally that some people are stronger than others, and so on and so forth. In that regard, inclusion has to be about pulling these people who have been historically marginalised from these systems in the processes of remaking them.

The first step is to give an equal platform, and a platform that is run by them to tell their stories and to be aware of these deep-rooted issues. And when we work towards overturning them it has to be collaborative. I am not saying that neurotypical people are our enemies, I’m not saying that we should marginalise these people who don’t have these experiences that we do, but that it should be a more collaborative process in considering a newer, more transformative system. Perhaps, it is quite scary that society is so fundamentally different and operates from a logic that is different from what we are raised in. But perhaps it’s not so bad to take the particular chance in that regard.

Fadiah: Thank you so much for your question, and I think you have already summed up what both of us wanted to articulate in our own chapters - that all these struggles are intersectional. We are not just struggling for one course, but when we struggle, for example, against incarceration, we’re talking about abolition of very punitive systems, then we examine what meritocracy means, how does this have repercussions on our education, and how this leads into issues of labour and migrant issues, among others.

I derive a lot inspiration from the Mad movements from other countries. I mean it hasn’t really happened in Singapore, but Mad movements, critical Mad studies and so on is about reclaiming that power and I think it comes together with abolitionist movements. In the US, it goes with the movements for prison abolition, talking about continuing effects of slavery, and others. I hope as a start, we could draw inspiration from such movements and see how that could work in our own local environments.

I really love the work that you do in Transformative Justice and I think it relates to other forms of struggles against oppression such as disability rights and anti-psychiatry as well.

Jennifer: Meng Ee, would you like to close the panel?

Meng Ee: Thank you so much. Just now, just before it started, I asked Jocelyn and Fadiah, how filled was the room? And they told me, “75 - 80% of the room is filled.” That is fantastic. So excited to hear that so many of you chose to come on a Saturday afternoon to listen to this book launch and listen to the panelists.

I think this is a milestone for disability. The content and work that is now being collected as a volume. And it’s really exciting. I think the potential now is to see how this book impacts our society.

I’m certainly going to be sharing it with my students. And those of you in the audience with family members and friends, we hope you do the same. This is very much advocacy work, right? That we just talked about.

And how much more depth can we get society into through raising the disability banner? And getting that shared not only within, as I said, in the usual issues of welfare and social policies? But I think, in 2023, as we march onto the next... we had SG50, so SG100? Can we become a lot more inclusive? So that disability doesn’t become a unique topic of conversation, but very much a part of the general conversation? I think this is the beginnings of how we’d like to see the dialogue deepen and further develop here in Singapore.

So thank you so much to everyone for being here. To Alvan, Jocelyn and Fadiah for really sharing. As I said in my opening, I think so much of the sharings have been very vulnerable. We really appreciate the openness and that willingness to make ourselves vulnerable.

But I think in that sharing, in that bold step, and that preparedness to be vulnerable, is where we also find the solutions and ways to move forward. To deepen the disability campaign as we step forward. I look forward to continuing this conversation and deepening our network here and beyond. I think Ethos has a few packages set up in how the topics here can be furthered as book club topics and so forth.

I want to thank, of course, Professor Dan Goodley, who’s unfortunately not able to be with us.

Victor, thank you so much as always. Miss you in Singapore, but look forward to continuing our conversations, wherever you’re in the world. Thank you for staying up and goodnight to you and your family.

🙌

About the Speakers:

Alvan Yap is an educator, writer, and editor. He was a special education teacher and the playwright of the play Not In My Lifetime?, a play about special educations in Singapore. Alvan has worked as an advocate with the Disabled People's Association and is currently serving a management role with a social service agency.

Nurul Fadiah Johari is a researcher who has written several pieces in local publications, such as Perempuan: Muslim Women in Singapore Speak Out, Growing Up Perempuan, Budi Kritik, and The White Book. She is interested in examining intersecting problems of patriarchy, capitalism, and racism, and their implications of mental health and trauma, especially in the lived experiences of minority women.