"Humans as a whole need to think beyond themselves": Making Kin Book Launch

Livestream of Making Kin Book Launch

The book launch of Making Kin: Ecofeminist Essays from Singapore was livestreamed on the Ethos Books Facebook page on 6 November 2021. You can watch the livestream above and access the full transcript of the programme on this page. Portions of the transcript have been edited for clarity.

SADeaf Terp provided SgSL interpretation for this event.

--

About Making Kin: Ecofeminist Essays from Singapore

Making Kin contemplates and re-centres Singapore women in the overlapping discourses of family, home, ecology and nation. For the first time, this collection of ecofeminist essays focuses on the crafts, minds, bodies and subjectivities of a diverse group of women making kin with the human and non-human world as they navigate their lives.

From ruminations on caregiving, to surreal interspecies encounters, to indigenous ways of knowing, these women writers chart a new path on the map of Singapore’s literary scene, writing urgently about gender, nature, climate change, reciprocity and other critical environmental issues.

In a climate-changed world where vital connections are lost, Making Kin is an essential collection that blurs boundaries between the personal and the political. It is a revolutionary approach towards intersectional environmentalism.

🐢

Arin: Hi everyone! Welcome to the launch of Making Kin: Ecofeminist Essays from Singapore. Thank you for joining us on this Saturday morning. We’re really excited for the conversation that will be taking place today on ecofeminism and kinship. I’d like to introduce our speakers today.

Next we have nor. nor is a Singaporean artist whose practice is rooted in self-portraiture. Their works span the disciplines of photography, film, video, performance, text and spoken word poetry that engage with ideas of belonging and identity through frameworks of gender performance, ethnographic portraits and transnational histories.

Next we have Dr Serina Rahman, a Visiting Fellow at the ISEAS-Yusof Ishak Institute, where she examines issues of (un)sustainable development, rural politics and political ecology. She is the co-founder of Kelab Alami, a community organisation that has worked since 2008 to enable a fishing community in southwest Johor to participate in and benefit from unavoidable surrounding development and urbanisation.

Lastly, we have our moderator, co-editor of Making Kin, Angelia Poon. Angelia Poon teaches Literature at the National Institute of Education, at NTU. Her research interests include postcolonial theory and contemporary Anglophone literature with a focus on issues pertaining to globalization as well as gender, class, and racial subjectivities. Now I'll pass the time over to Angelia to start the session for us.

Angelia: Thanks very much Arin, and thank you everyone for joining us this morning. I’ll start by reading out our land acknowledgement. I’ll start, and then Esther will take over.

The editors of Making Kin would like to acknowledge the land we rest and reside on, the land that inspires our work and pervades our dreams. Many of us are descendants of immigrants, who left their ancestral homes from across the seas to make this land their home. We give thanks to this land for caring for our ancestors, which has allowed us to now call this land our home.

Land reclamation has expanded Singapore’s land mass, but this has come at a heavy price to our neighbours—for instance, the loss of traditional mangrove communities in Cambodia, and entire islands disappearing in Indonesia.

Esther: To further our economic prowess, indigenous communities, the descendants of the Orang Laut, were forcibly removed from their island homes between the 1960s–1990s, which are now Big Oil refineries, a massive landfill for the mainland’s waste disposal, entertainment hubs, military bases, expensive residences for expatriate communities.

We give thanks to the land for sustaining us in the face of deforestation and urban redevelopment, which began in colonial times and persist today.

We recognise that we inhabit this land along with our more-than-human kin: the fish, corals and marine life in the sea, the birds of the air, the insects, animals, trees and plants that inhabit the earth, and the beings beneath.

We give thanks too, to the lands of our imaginations and travels, to expanded notions of home and belonging, and to kinships and entanglements with places that continue to nurture us from afar. Here, we raise our hands and give thanks.

I think ecofeminism, some of us might understand this as how it centers the woman in a web of relations to the earth, and ecofeminism is mainly primarily interested in woman-nature relationships and how these entanglements are typically negatively impacted by patriarchy.

Ecofeminism also emphasises the importance of reciprocity and care, as well as cooperation and love for our earth and our kin, which may be human and more than human, and it resists the path of dominance and domination of earth, of others, as well as violence. Instead it is open to mutual connections and interdependence.

There is also a deep recognition of our shared existence as earthlings, meaning as inhabitants of Earth, and that if we want to be cared for by our earth, we need to first care for our earth.

I think you will also notice that in the essays in Making Kin, there is this recognition that our existence is only made possible through the thriving of others, and so fundamentally, we could say that ecofeminism contradicts a patriarchal, capitalist way of thinking in terms of individualism, competition, profits and progress.

Lastly, I think the essays in Making Kin present practices of kinmaking, of kinship and care, and relational ways of being on earth. If you have the book and you have read the introduction you will know that this is also what we mention about how ecofeminism is founded upon a politics of relations and I think the contributors in these essays do that as well in various ways and how they live out the experience of being a woman on earth.

This concept of kin-making as person making is taken from Donna Haraway’s book, Making Kin: Staying With The Trouble. And in terms of how we can make kin with places and with earth-others beyond the notion of ancestry and genealogy, which is I think a more conventional way of defining kin, and so we want to look beyond that. That’s my introduction to what defines ecofeminism and how this is engaged with in Making Kin. Angelia will continue to share about the personal essay.

Angelia: Thank you Esther. I just wanted to say a few words on why Esther and I decided on the form of the personal essay. We felt very strongly that the personal essay form was especially suitable for ecofeminist reflections, as it is an accessible form while being also expansive and flexible enough to accommodate a wide variety of views and ideas. For us the personal essay form hinges on the uniqueness of the personal voice that is conveyed in writing. So that voice may convey intellectual abstractions, or it may zoom in on the minute and the mundane when teasing out a memory.

Making Kin demonstrates our desire to revive the personal essay form in the consciousness of Singapore literature, because it is still a relatively underdeveloped form in Anglophone writing here. That’s all I have to say about the personal essay form, so we can move on to start our panel discussion. Perhaps here, at this point, to start our discussion I could invite Esther to read from her essay, which is entitled “The Field”.

Esther: Thanks Angelia for that. I realise that our backgrounds are mirroring each other. It’s really quite poetic, it’s quite nice. So I’ll be reading from “The Field”, which is an essay that reflects on this field of my childhood which is no longer around, because it got redeveloped. So this is just an excerpt.

Mary Oliver writes in Upstream that a writer’s subject may just as well be what she “longs for and dreams about, in an unquenchable dream, in lush detail and harsh honesty”. And yet, to long for the subject of this essay, the field of my childhood, is to long for a broken and irretrievable past. A place or habitation I can no longer enter in the physical sense though I keep returning to it in my dreams, in various iterations and permutations, the field changing each time, but still the same.

The field of my dreams was once a field of green, inhabited by wildflowers I would only later learn the names of. One day, upon visiting my mother, she hands me two books I used to own as a child: A Guide to the Wildflowers of Singapore and A Guide to Medicinal Plants, scientific handbooks published by the Singapore Science Centre. I flip the cover and on the reverse side, my mother’s name “Mrs. Vincent Elaine” is written in blue ink, dated “10/3/99”, against paper ringed with the sepia of mould. These would be the same two handbooks I would consult twenty one years later as I revise a poem for a Creative Writing Graduate course about childhood, memory and change.

But what of the field, you ask?

To paint a landscape from memory, one has to take certain liberties. But let me endeavour to recreate the scene as accurately as I can remember. As accurately as it is deserving of memory. To a child, the field was an immeasurable expanse of grassland, a gentle slope leading up to a plateau where all around is an ocean of green. Of course there were already high-rise blocks bordering the edges of the field, but a child’s mind is immune to limits and boundaries, and so I invented stories and places, telling myself that to my north was a strange and forbidden land (in reality, my mother had disallowed me from venturing too far, the field containing my adventures and exploits), to my east, the road of daily traffic, to my south, my castle, my home, and to my west, nothing of real consequence.

The adventure begins with waving goodbye to my mother, walking out the house gates in slippers, my fingers trailing the white walls of the corridor, fingering the peeled beige paint of the metal staircase. Sometimes, if I was lucky, I would be greeted by a tiger moth resting on the wall, but if not, I would skip down the three floors of stairs, walk past the lift landing on the ground floor, towards the pillars at the void deck, phone booth to the left, letter boxes somewhere nearby. Past all that, the block would end with a narrow strip of metal drains, and all I had to do was take a breath and cross over, and I would enter another world.

Yeah, so that was “The Field”.

Angelia: Thanks very much Esther, that was really lovely. It’s really interesting to see how an empty field can hold so many imaginative possibilities. Do you think you could share some of your ideas about the relationship between memory and ecofeminism?

Esther: Thanks for the question, Angelia. This personal essay is very close to my heart, as all the topics are to the contributors, as you'll see when Serina and nor read their essays.

I think there is no clear link between ecofeminism and memory, meaning that I feel that memory itself is not feminist. But what is being remembered in terms of the memory and how memory is presented, I think that can be ecofeminist in nature, if we return to the definition of what is ecofeminism that I shared earlier on.

I think first of all we need to distinguish between memory and history, what is recounted from the past and who presents this history to us, and what is personal memory.

There’s also cultural memory; cultural memory actually refers to interconnections between memory, culture and identity. It’s also very interested in the relationship between the past and the present, as well as how individuals, how groups, how societies remember, rework, bury, or forget. So there’s also this forgetting, aspects of the past in order to make sense of, repair, and reconstruct the present. I’m reading this definition from the University of Brighton.

I think in terms of cultural memory, there is a need to create collective and shared memories, to remember our kinships, our entanglements, our mutual thriving with others. That’s what Making Kin attempts to do as well in the essays. It is a way of recollecting and reviving certain silent, forgotten histories, and stories, and narratives.

I would say in terms of representation of memory, if we think about an ecocentric notion of memory and remembering – for instance if we ask ourselves, how does the natural world remember? We usually think about the human or the anthropocentric notion of memory. But what about the natural world, for instance? How do migratory birds remember the routes they take? And it is also quite sad, because they remember the migratory path, but when they return to these places, what happens when these places change with urbanisation?

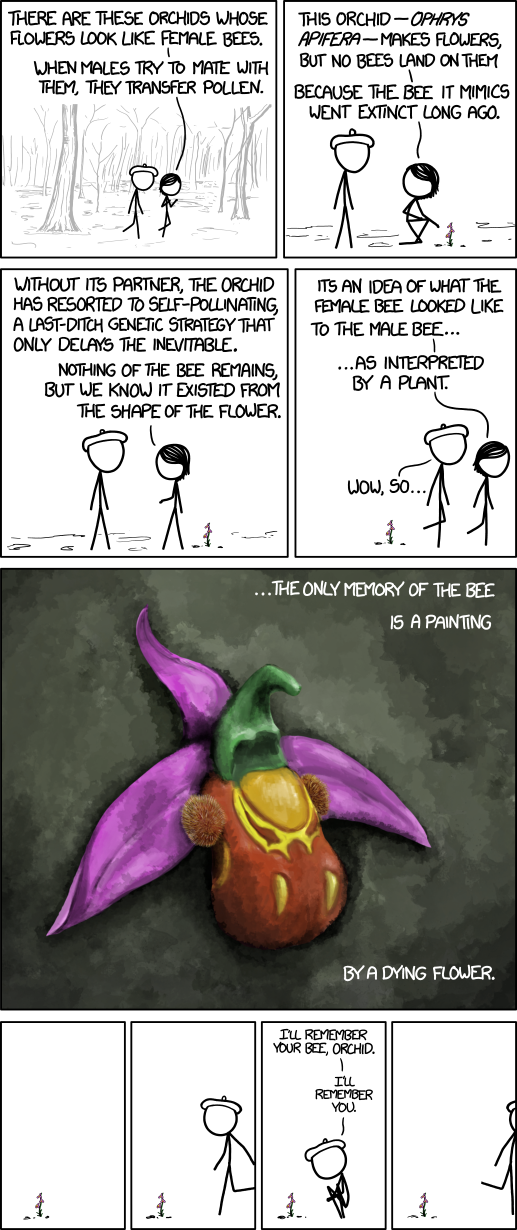

I also would like to share about the bee orchid just to illustrate my point on memory. The bee orchid can be found in the UK and I think in part of Ireland it also conserves a species of plant. I thought I would share this comic strip [from xkcd], which I feel is a good example of an ecofeminist way of remembering something.

I thought this was quite poignant and wanted to share it with everyone.

I thought it was quite a good example of how an ecofeminist way of remembering might be envisioned. So of course in the essays we see that, but also in other art forms like comics – this is one way in which stories, myths, rituals, or even histories, narratives, might remind us of our kinship to others. Like how the bee is kin to the flower, and now without the bee, the flower still remembers. So that’s one example of nature’s way of remembering. And it’s quite sad, but that’s what it is.

Angelia: That’s great Esther, I really like the comic that you shared, and the reminder that nature also remembers. I think your explanation of memory in terms of the personal as well as cultural and natural is a very good one to think about; especially since we tend to forget the ways in which nature can remember. I wonder if nor or Serina has anything to say about memory and how that impacts the work that they do? Would anyone want to go first?

nor: I could share a little bit. Esther, when you were sharing about your essay “The Field”, I think most of us would have similar experiences as well, I think when you’re surrounded by the concrete jungle. My sisters and I used to roll down the hill of Bukit Ho Swee, and it was so much freedom. The tiger moth, that’s also a very significant memory of mine from childhood, and the tiger moth would mate, and for some reason they become heavier when they fly, so it was easier for them to land on our hands. That was a huge part of our memory.

Serina: My memories are all of the sea – I see lovely things on land but because I travelled as a child, so I was lucky, I got to swim in the Red Sea at very young age before all the development around Jeddah. My dad tossed me in the ocean when I was six months old, and I was really lucky to be swimming off of HK when I was 3 or 4, but it was in Jeddah that I started snorkelling, in the Red Sea.

So now whenever I dive, and I’m in the water, that’s my benchmark, to see that kind of colour and life and clear water, and that just keeps flooding back, all the time.

Angelia: That’s great, thanks Serina. I know the sea comes across very strongly in your essay, and that was lovely to read about that. Esther, did you want to say more about memory or what memory is like?

Esther: No, it’s okay, I think it’s good to bring in nor and Serina, because I think we were also having this conversation the other day at the launch of my other book Red Earth, and how Gina (Hietpas) was saying that we think we have personal memories and personal kind of rememberings, but our experience is actually not unique. It’s actually kind of a collective and shared consciousness, shared memory, shared trauma, shared joys as well.

So it’s very nice to hear that nor had similar memories of relating to nature and to a field. And I think Serina, as well, even though you mentioned that you’re very close to the sea. I think that’s the idea, of the earth, and the earth is made of land and sea, and we just find our own ways of relating to various parts of the world based on where we are. I think to add to Angelia’s point, I’ll just add two more points.

So it’s quite different from the patriarchal, phallic way of thinking of evolution, as like a spear or implement of violence. Le Guin posits that the story could be read as a carrier bag or container. And so then I was thinking of memory as a carrier bag itself; memory as a thing that holds something else. And if we think of how carrier bags or containers or holders are made, it’s made by knotting or stitching or weaving or braiding, to hold these shared communal collective histories, collective stories, which are both personal and yet shared.

So I think the personal essay does a great job of being a carrier bag of memory. The second point I wanted to mention and just share with everyone is also how we could think of memory as a voyage of returning. So Le Guin also writes in her book The Dispossessed that to be whole is to be part; the true voyage is return. So the idea of an ecofeminist lens, some people may say that it seems like a return to older ways of thinking, older ways of being.

So the truth is that true voyage is return; we always think that to progress—the idea of progress is also a very capitalist modern kind of thought, like to move forward, but actually I think the beauty is in returning home, returning back to stories that have been silenced, untold, the dispossessed stories, the dispossessed memories, from which insights may be gained. So I think this is a way in which memory can be engaged through an ecofeminist lens. I hope that offers some insights.

Angelia: I’m struck by this idea of the carrier bag and how it predates the spear. It also links to the whole idea that we want to convey with Making Kin, and it’s a more hopeful idea as well, that the first thing human beings constructed was a container to share with others, and that’s a form of Making Kin, rather than a weapon with which to kill your kin. So I thought that’s a really nice way to think about it. So perhaps now I could ask nor to share her essay, “Semangat in Practice”?

nor: Thank you Angelia. I’ll start my sharing with the poem that is part of the essay, “An Ocean”

the inhabitants of Atlantis

will rise again

This time claiming permanent

independence,

and with a booming voice:

An announcement

Manusia terlalu taksub

Pada asteroid

Pada debu bintang

Sehingga leka

95 peratus lautan

Masih belum diselami

Dan belum dijejaki

Kerana

Mereka takut kelemasan

I wrote this poem in 2014, while I was serving in the coast guard. I had the opportunity to patrol the Southern waters of Singapore and often caught glimpses of the Southern islands—Pulau Sudong, Pulau Pawai and Pulau Senang. While I originally wrote “An Ocean” as a love poem to a boy who would not love me back, I have to say it was the semangat of Singapore’s southern waters that breathed life into this poem. There was something heartbreaking about how the island my paternal grandmother hailed from was now a military training ground. This poem was a way of remembering my people and the ocean. While my paternal grandmother is a Singaporean islander, my Indonesian mother came from one of the islands in Riau. According to my grandmother, prior to strict immigration and border control, she used to travel to my mum’s island by sampan.

When I was 10 years old, my Indonesian mother was stopped at the Immigration checkpoint of Harbourfront Ferry Terminal. This was something that happened frequently whenever my family waited for incoming guests from my mother’s hometown. The immigration officers were close to sending my mother home until they saw my grandmother and me frantically waving to her outside at the arrival hall. The reunion was poignant. My mother cried as it was the first time in many years that she had entered Singapore to be with me again. Every year during our National Day, Singapore parrots the narrative of our transformation from a fishing village to a first world country. In my work Sekali Lagi, I ask: Are the fishermen not our people too? Oftentimes, I wonder how differently Singapore and our neighbouring nations would be if we moved beyond the interests of our self-imposed borders. What if we looked at the sea as a connector and a living continuous flow of energy and resource instead of seeing ourselves as isolated islands?

Ecofeminism asks us to think of our relations to the Earth and the environment, in all aspects of our lives—gender, sexuality, ethnicity and class. To know one’s self is to know one’s history. To know one’s history is to know one’s land. To know one’s land is also to know one’s sea. To honour the Earth—and all of its elements—as something alive, full of semangat, is to consider the imbalance we will cause to others and ourselves when we do not honour the very ground that we step on and the seas that surround and nourish us. To think of the seas as a shared connector is also to think beyond the often violently created borders of states and the needs of people outside our country who will be impacted by our wants. When we are able to acknowledge the interconnectedness of our identities—our shared histories beyond the lands we occupy and our interdependence through the seas we share—instead of competing capitalistically to be a nation with the best resources and living conditions, maybe then will we be able to connect to the semangat of Mother Earth again.

My art practice did not begin with an environmentalist slant. However, I eventually realised that it is impossible to separate the self and the body from the land and the sea you come from. The semangat of the tanahair and Bumi will always find its way to you.

nor: Sure, thank you for the question. For me, when I think about art at its simplest form, I think of it as expression first. Before any of us can write or even speak, if you just give a child a crayon or any form of pencil or a paintbrush, children will be able to express themselves freely. And oftentimes it’s the first steps that we take to be able to share our stories, even though as a child you might not exactly be sure what the story is. And then as a child grows up, we teach them tools such as guiding lines, colouring within the lines, shading, curves, and other visual tools that can help better tell a story.

So when I think about expression and storytelling in Singapore, I think of these two questions: what type of expression gets celebrated, and who gets to tell their stories. And then from these two questions you can further expand on them to think about what type of images are available in our galleries, who are making these images, who are winning awards and commissions for these images, and what kind of images are we lacking in?

I think the stories and images we share are also dependent on whether our forms of expression are celebrated or stifled. For the longest time, I felt that my story, and my family’s story were something to be deeply ashamed of. I don’t know where or how that came about. But I think all the way up till my diploma, I felt these stories were important to me but you don’t usually share these stories. I think at the end of the day it also boils down to who deserves to know these stories.

A big part of why a lot of our stories and our expressions aren’t being shared is that the references that are available or accessible don’t exactly encourage the stories we have. Sometimes I couldn't find the right flowery words or right angle and lighting just because the references were not right in front of me. I think usually you can’t tell a story if you’re told from young that the way you express yourself isn’t the most optimum or effective.

Think of it as being scolded for colouring outside the lines or adding on elements to a colouring book that’s not there. And also, are we allowing space to hold expression that we may not necessarily grasp immediately, and by acknowledging that there's potential for more stories, more truths to uncover in the languages and the vernacular that we’re not so used to.

Angelia: Great, thanks. I really like the idea of expression, especially vernacular expression. And I agree with you, I’m not sure where it comes from, but I think that there's a certain embarrassment about the local, feeling that something is not good enough to share with everybody. But I think that through your art practice, you’ve shown that's not the right notion to have. I wonder if Esther and Serina have any thoughts about this, what they think about expression and the importance of the vernacular, I suppose, and the local in expression.

Serina: I’m jumping in, I want to say that nor, I’m so proud, I would be so honoured to be you. I think you’re amazing, and you have such amazing roots you know and you can touch and feel and see! My work in this village is to tell the local people to be proud that they are descendants of fishermen. And you know, I grew up travelling, I didn’t have roots; I am constantly searching for roots; I have no home to go back to.

But you have your island—okay now it’s a military base, fine—but you do have that and I think Singapore is desperately trying to find this nostalgia, these roots, these origins that are there but are buried. If I was you I would be so proud of you, to be you. I really wanted to say that. About the vernacular and the expression, I think it’s a symptom of development and materialism that we find shame in the simple and in our origins. The nation really needs to evolve that; because if we don't have our history we would not have us. If we did not have our original people, there would be no Singapore. This needs to be recovered, not buried.

Who needs the colonial masters; we need our origins. It’s people like nor who should speak more and have more art and have more space, and have more platforms like this, to have the authentic. Not to romanticise these issues, but to speak the authentic, the difficulties in crossing the borders. The fisherman I live with, they also used to cross freely between here and Tuas, and of course it came to an end. This is you, the real you. So speak! Tell people! I think there is a thirst for it now, and I’m so glad I met you on this panel!

Angelia: Hear, hear. Esther I wonder if as a poet, you might have any thoughts about this?

Esther: I think just to add to what Serina mentioned; her affirmation of nor; I am quite envious of you as well, nor. Maybe what Angelia said about embarrassment, maybe sometimes we might feel shame about ourselves or our stories. I think it’s a side effect of colonialism, the canon and imperialism of what is important, which narratives are important, and then which narratives are not important.

People in power deciding that this is the official narrative, and this is what we want to hear, this is what we read about in textbooks, this is what we see in the media, and so then we internalise that everything else falls by the wayside – like what I referred to earlier, the dispossessed stories, the silent stories, the untold stories, which were always there, I think need to resurface. So I agree with Serina that there’s this hunger for reclamation. Maybe this is also tied into the eco crisis, the climate crisis, and also moving past—hopefully we are able to move past our colonial history, not that we erase it as well, because it is part of our story, it is part of history, but I think we also need to return to older times and older ways of being before colonialism.

So I feel that the colonial history plays a very big part. Because it also influences the stories we read, the books that we read as children, and then the kind of narratives that we would have internalised and felt were legitimate, the voice that we felt were legitimate. So I think that’s what I have to add.

Angelia: Thanks, Esther. You’ll find many local, strongly rooted stories in the collection, so I hope listeners will be able to enjoy more of the local through this collection as well. Perhaps now I can also ask Serina to read from her essay; the title of her essay is “The Sirenia has Found Her Home”.

Serina: Thanks again for having me on this panel. Because I realise everyone else is reading from the front, and I’m reading from the end, and pretty much giving away the plot. So I need to give some context.

So as I’ve said I’ve travelled the world, but I’ve been living in this fishing village since 2008, and I’m in a fishing village in the southwest of peninsular Malaysia, in Johor. And it’s a very different world and life from what I had before. My dad was a diplomat and we travelled well. I was a very fortunate child living this third culture childhood, and always looking for my roots. So I think my whole life has been a journey to find out where I’m from.

But my time here has been evolutionary in discovering that perhaps maybe my dreams that I thought I was heading towards were not what I wanted. So the excerpt I’m reading brings you to the end of the journey, not that it’s ending here, but where it is now, where I’ve already gone through the rest of the chapter earlier that you can read when you buy the book. It tells you how I got to this point.

But my point is that what I’m about to share is a bit of insight into the people I’ve been engaging with for the last 12, almost 15, years, and the people who are now sort of this family that I sometimes want or don’t want to accept. This is more about making kin, I’ll explain thereafter. Let me pull it up so I can read it. The excerpt is this.

Not long after his return from KL in 2015, Shalan set up a seafood market to ensure that the fishermen earn a fair price for their catch. Pasar Pendekar Laut (Sea Warrior’s Market) now pays fishermen twice what they used to earn as he takes a fraction of the amount that other middlemen take above the landing price. Shalan also helps them weave their nets (which frequently need to be replaced), as well as finances boat and engine repairs. The craft of tying nets is preserved through this effort, as he has forced all the younger fishermen to learn the skills and work with him to support older, slower fishermen with nets. This is all documented by the Kelab Alami youth and myself.

The boys have been integral in this effort, initially heading out to sea themselves to learn the trade, then working with the fishermen to develop standard operating procedures for our sustainable fisheries and endangered species reporting systems. The fishermen now release and report critically endangered species such as eagle and shovelnose rays, and are roped into our research by providing expert knowledge on endangered species locations and habits. Shalan ensures that the seafood caught is a minimum size and quality—those that don’t make the grade are released and unpaid for.

The youth have also set up a food stall nearby to ensure that the fishermen have freshly cooked food to eat when they return from sea, and market customers are enticed by the scent of traditionally cooked fresh seafood. They often end up buying more raw catch to have it cooked on the spot for them to eat or bring home. At the same time, customers are taught about seafood seasonality, are enlightened on the hazards of artisanal fishing, and the skills required to bring in the seafood for their tables. They are also made to understand that the fishermen must be fairly compensated for their effort, craft and knowledge so that they are better able to provide for their families.

This then, is how I earned my daily perch at the jetty as cashier and logbook keeper. The arrival of COVID-19 has closed the Singapore-Malaysia border and I can no longer go in to work every day. While I am able to work from home, I use my mornings to soak in the sea breeze and fishermen’s stories when they return with their catch. I document their reports of the wind, water and weather, and photograph the fisheries species or bycatch as they come in.

I feel like a bit of a fixture at the jetty now, no longer deemed as improper or inappropriate as before. The fishermen, by nature, are a relaxed lot. They have seen me haul petrol tanks, engines, baskets full of fish and crabs and are used to my incessant questions, offering all manner of information on species identification and behaviour. They know that I am not just by the water but also in the water every chance I get. They have taken us out on research trips, and have watched with some worry when I dive into the murky shallows around the seagrass meadows and island. The first time I headed out to dive, Shalan’s grandfather who lives at the jetty asked me in surprise, “Girls dive too, now?” Now they just ask what I found.

The fishermen marvel at my excitement at seeing creatures they always see but never knew were special, and seem to have taken on more responsibility in cajoling others to fish more sustainably. They are also actively looking out for bycatch species that we may not have seen before, and reporting on every change in the weather, water and winds. My nagging has made them a little more careful about the rubbish they almost automatically toss into the water.

There are very few other women about. Only a handful accompany their spouses to sea to do actual work. I’ve only known two who head out on their own—both referred to as ‘tomboys’ by the community. While I am always happy to see both, and engage in light chitchat, there is nothing as intrusive as the interrogations that I used to endure in my early days in the village. I see the women who accompany their husbands as they pass by our jetty and they wave and smile in quiet acknowledgement of another female who knows the seas as they do. Many women in the village don’t.

And that’s my excerpt. So, it’s kind of odd, but when you buy the book, you get a better picture if you read what happens at the beginning.

Angelia: Thanks so much Serina, I really like what you just read. And I think your essay really encapsulates the whole idea of what Making Kin is about. The way you have reached some kind of equilibrium with the village you’re in.

So maybe I could ask you to talk a little bit about how you’ve invested, obviously a lot of effort and time, in making kin at that village. What would you say are some of the hardest challenges you had to overcome in making kin?

Serina: The story is that I came here to teach the kids about the habitat. I worked with this one guy who was our boat man at the beginning. And then after a number of years, we ended up getting married.

So the biggest struggle for me was understanding and accepting that I essentially married the entire subdistrict. Because I’m a very ‘on my own’ kind of person, and I really don’t want to engage with people so much. So then I ended up marrying the entire district, and then my life and my business and my property was suddenly everyone’s knowledge and business and property.

So this was one of my biggest issues, I suddenly inherited an entire subdistrict. Getting used to how the community functions is also very difficult, because from being alone and not having to deal with people–everyone is pretty much in your face, and you have to accept them. And you can’t ignore then, because then you’re arrogant, so you just kind of have to be nice to everybody whether you like them or not.

The other bigger issue is really understanding local women; and this is one of the reasons why I struggle with the term ‘feminism’.

When I first moved here in 2007-2008, I was fodder for gossip. Nobody knew who I was or what I was doing. I was this rich kid from KL who was coming here, and in their minds here to steal their husbands and boyfriends. Local women’s approaches to life and their goals for their daughters are very different. And this then influences how the daughters think for themselves. It really is a change in mindset that I struggle with.

Because for some of these girls that I worked with, we had many who were part of Kelab Alami, they sort of bought into my story of, “You can do more, you can go out, you can engage with people.” But their mothers, their aunts, their boyfriends,were telling them, “No, this is not for you, you need to stay at home.” I have had mothers screaming at me, at weddings and at the Shell gas station, saying “My daughter’s place is in the kitchen. She’s supposed to be here to serve her brothers and us! She shouldn’t be with you working in the environment.”

I’ve had mothers tell me no, there's no need to teach my daughters English. They’re just going to get married and work in the factory in front of the house and stay home. Those same mothers came to me and asked me to teach their sons English. I said no. So these are the things I struggle with. And for this reason I completely ignore—okay no, I can’t say that—I avoid local women as much as possible for my own sanity—there's too many questions, there’s too many conflicts in the way we think—and that’s difficult. So those are the main things I struggle with.

Angelia: Thanks, Serina. I appreciate the difficulties there, to navigate and negotiate different ways of thinking, and probably in the way that the village sees you as an outsider, someone cosmopolitan coming in. I think your essay really captures all those challenges and difficulties very well. Wonder if nor or Esther have anything to say in response to the difficulties of making kin? Or perhaps the pleasures of making kin, if you have something to share. nor go first?

nor: I think for me, making kin through my art has always been something joyous. Especially when I’m able to meet other transgender, or queer, non-binary people, and seeing how they approach their visual storytelling. Because sometimes it’s not exactly the safest to take up space when so much of your existence is, I guess you can say, very political, when it’s not. In some ways I relate to Serina, the idea of inheriting something you didn’t ask for. It’s something that we all experience in one way or another. Coming to terms with who you are, your beliefs, your values, and how it might not make sense in your immediate locality or the people around you.

Making kin through strangers is something that can be so–the word is not liberating, but it can provide a lot of comfort to see how other people navigate such circumstances. I must say that I have been very lucky. Singapore is really small. So when you do meet somebody—If you don’t, somebody will point you to a person who is like that.

Angelia: Thanks for that, nor. I just wanted to plug nor’s essay. Readers, if you read nor’s essays, you’ll read more about her art practice, and how she really uses art to recover memory—to me that’s really important, and also to express herself. And there are a lot of pictures in her essay as well, so that’s really worth checking out. Esther, do you have anything to share as well?

Esther: I think I’ll just make a point very quickly because I'm also quite mindful of the time. I think from what Serina and nor have shared, it’s clear that kin making is not really—I would say it’s a difficult process. It can be quite challenging and frustrate us sometimes as well. Because we’re all such different people from such different cultural contexts, with all the different intersectional parts of our identities. I think for me personally, I’m more intrigued by making kin with natural elements, with nature.

Similar to Serina, I have this desire and search for my roots due to my mixed ancestry and ethnicity. The idea of kin making when I look at nature, is to transcend that, ancestry and genealogy. So much of myself I don’t know—my paternal grandma was an orphan, she was left at the door of the CHIJ orphanage. There's so many questions. Even my paternal grandfather, all I know about him was his name and that he was from Sri Lanka, and he came here to begin a new life.

So I think that all these not-knowings has led me to look for who I am in a different way, to look at myself as a daughter of the Earth, and to connect with my roots in a more spiritual sense, in nature. So that’s what I wanted to say about kin-making.

Angelia: Thanks very much, Esther. Just also to say, when we talk about Making Kin, you’ll find that many of the essays are not only about human relationships, but making kin with other species, with animals, with nature. So I hope that some of these essays will resonate with our readers. We’ve touched on quite a number of important ideas that this collection raises from having nor and Serina read, and also Esther. You’ll see that memory, both collective as well as personal, natural, memory, play a big role in the essays that we have.

nor talks about her artistic practice, and we have quite a number of artists also featured in this collection. And I think Serina’s work, how she has sought to make kin, and her valiant struggles over there, I think that a number of other essays also talk about their difficulties in making kin, or finding a community of acceptance. And what they had to go through. I think we have covered quite a lot of the important essays that I hope you'll find in our collection. So maybe if anyone has any last words they would like to say? If not I thought I would take a look at some of the questions that our audience might have posed for us? Would anyone like to say anything before we move on to that? I think I’m the holder of the questions, it’s on my phone, so shall we do that?

Okay so maybe I’ll pose this question first: How do you think an ecofeminist practice of care might help us deal with the climate crisis? A huge question I know, but also a very timely one, given COP26 and what we read everyday in the media about climate change.

Esther: I agree with Angelia, it’s really quite a broad question, it’s difficult to answer, I think, in one sitting. An ecofeminist practice of care... I think in general, a lot of this has to come from policymakers as well.

In terms of our collective impact on our environment, it’s very clear that people with the greatest power (like organisations, corporations, governments) – they do need to really relook whatever it is that needs to be relooked and then take action there. I think we also need to think beyond human notions of inhabiting the earth. If we think about an ecofeminist praxis of care, we need to look at our earth in a more eco-centric way.

That may pose quite uncomfortable questions and topics of discussion. For instance, our human population. It is very clear that (the) human population on earth, especially people who come from so-called developed nations, in terms of our consumption, in terms of our habits, we do leave a very heavy carbon footprint on the environment. So then the question is, if we want to make kin and care for our earth, we need to make certain decisions, like choosing not to have children for example.

That’s why these are very controversial topics, but I think they are still important to engage with. Even things like food, the food that we eat, that’s the basis of sustaining ourselves. But then again, if we really think about an eco-centric way of practicing care, then we would also care for the food we consume, how the animals are treated before they are slaughtered to sustain us.

So I think it’s really quite difficult to respond to this question, but these are just some ways in which we might start to think about it, beyond just anthropocentric ways of looking at the climate crisis. But to look at our kinships and entanglements with various others that need to thrive in order for us to thrive.

Angelia: Thanks Esther. I think partly this question is really showing us how the personal is political and the other way round also. What we do with our own personal decisions and how that might affect the climate and the earth. And when you talk about food, I also just wanted to point out that one of our essays advocates becoming vegetarian, as doing your part for the earth. That’s one thing people might like to think about. Do Serina or nor have anything you would like to add about this idea of the ecofeminist practice of care, and how it might help the climate crisis? Perhaps an ecofeminist practice of care where we put women at the centre, and also think about how we can do our part, whether in local communities and smaller groups, to help with the climate crisis. Serina, would you like to contribute something?

Serina: So this idea of care and putting the female at the centre. I think it would differ depending on where you are in the world. In Malaysia, for example, the woman really is at the centre of everything – the mother is everything and everybody follows what she says, and she’s treated like a god. I struggle with that, but I think in a society like Singapore’s, for example, perhaps ironically the woman is pushed aside a little bit more. The goal of achieving puts the mother’s role – all the multiple layers of work that a woman usually bears is cast aside and hidden by the women themselves.

The parallel between both worlds that I straddle is that it is often women making life more difficult for other women. Whether it is a mother’s restrictions on their daughters or women’s social pressure to achieve, from other women. Coming back to climate change, however, this idea of care and putting women at the centre really needs to reverse itself into thinking about ourselves and our impact on the world, and taking that step to act because of the impacts that our actions will have on others. So it is the empathy towards other beings, not just humans but also towards animals or plants.

I understand that the idea of a female is care but I’m not so wholeheartedly believing that all women are so pure and so caring because I’ve met some very evil women. So I think this is a human issue, not necessarily a gender based issue. Because then what about all the other genders that we have, where do they fall? I think humans as a whole need to think beyond themselves. I think in Singapore—no offense—there is a great desire to achieve for yourself. Whether it’s to compete with others, or to achieve certain goals, or “yeah, it’s not my problem, the government will deal with it and tell us what to do”. I think we all need to take that step by ourselves for ourselves and for others.

To be better people just to be better people, not just because the church or mosque tells you so. But because you know as a human that this is your duty to the world, and to this earth, which is 70% water, so to the seas. And to give back, because you’re here using up everybody's resources, you need to give back to the planet. That’s just your duty as a being, whether you are male, female, others, or whatever race or ethnicity you are. Yeah, my two cents.

Angelia: Thanks very much Serina for reminding us of the commonality that we have, as humans, and the duty and responsibility we have. I think that’s what all of us are committed to as well. nor, do you have anything to add?

nor: Adding on to Serina’s point, I guess the notion of care, right? To take care of the earth is also to take care of another person, and also taking care of yourself. One of the things I realised through my work is that, maybe specifically in the context of Singapore, a lot of people are not able to care about whatever’s going on beyond themselves. We don’t even have time to care about what we’re eating for lunch, because we’re just so exhausted, we’re tired. It’s reductive, but nobody cares, I think, in this capitalistic way of living.

Sometimes I ask my friends, don’t you care about what's going on, why is nobody checking in on other people when a certain case of racism is happening, for example? But nobody is checking in to ask how someone is feeling. And I’ve asked people before, why do you feel like you are not part of this? What really helped me empathise better was my friend told me, “That’s because I’m tired. I’ve been working the whole week. And I’m not even able to think about what I’m having for lunch. I can’t have space.”

So people who can’t give won’t give. When we think about care, how are we allowing space for that? If we can afford generosity for ourselves, to have that, then maybe we are able to have the same generosity towards others.

Angelia: Thanks nor, I think you’ve just reminded us of the importance of self care; we’ve been, in a way, hearing a lot more about that because of the pandemic lately. Hopefully that will also give us some time to think about how we can take care of ourselves in order to care more for others. Rather than (taking) care of ourselves in a self centred and very egotistical kind of way. I have another question that I think is quite interesting, so I’ll just pose it to everyone: Do you think ecofeminism can include religious practices like shamanism or animism that is deeply rooted in Asian traditions?

Esther: All these are labels, right? Ecofeminism is a recent label from the 70s when certain things were gaining traction. I think these kinds of ways of living, with reciprocity towards the earth, with care, with love towards the earth– these practices have existed for a long time, especially in indigenous/tribal communities. We see this manifested in what we now term as animism and shamanism. So I would say that all these are actually related, these practices– I wouldn’t call them religions, I think I’d just call them beliefs or philosophies. I think they draw from the same well of caring for the earth.

It’s also quite logical, because the people, the communities lived very closely with the earth. They would have to therefore look after the earth, because let’s say they look after the seals, and they ensure that the seal population is healthy then they’re able to live well, because they depend on the seal for sustenance, for food, to keep them warm–for clothing and all that. So I would say that it’s really this closeness and this kinship with the earth. And whatever you call it, shamanism, animism, I think is founded upon this very notion that in order to thrive, I need to look after the Other because the Other is a part of me.

If the Other does not thrive, I do not thrive. So I think there’s this very close connection and intimacy to understand that the self is the Other, and the Other is the self. This separation is something we are now dealing with in a more modern context. We live in terms of separation, we think in terms of separation: of the self from the Other, of the human from nature–the nature-culture divide. I’m not sure if this answers the question, but I definitely do see similarities across these philosophies, beliefs and practices. And I think ecofeminism just focuses a little bit more on the women, also because of the cultural context in which ecofeminism arose.

Angelia: Thanks very much, Esther. Maybe nor has something to share also– because I think your artistic practice deals a lot with traditional beliefs and practices as well, maybe something about semangat?

nor: I think my introduction to eco-spirituality was through drum circles, and healing circles, and sitting in, listening to practitioners who have travelled the world, and then coming back to Singapore and sort of sharing the knowledge that they've learnt. Most times I feel that, while there are many elements that I can relate (to), I think the most spiritual thing that I can do for myself is go for a two-hour walk in the park. Google Lens is actually our best friend. I think recently there has been a trend in, or rather an increasing consciousness in foraging. Especially in Singapore where foraging is illegal.

I think that learning the type of plants that are already available and around is such a great way to know your friends on earth who are not humans. For example, the Rukam Masam–am I pronouncing it correctly–the fruits that look like cherries that are just abundant along the streets of Singapore. I see birds eating them all the time and I’m wondering, can I eat them? And only recently, maybe last year, on CNA I found out that you can eat them. For me, it’s such a simple–it’s there, hiding in plain sight, I feel. I think maybe the most spiritual thing we can just do is to pause and walk, pause and look. There's this quote by Jhené Aiko–“If you talk to your plants, they will talk to you.”

Maybe the plants haven’t talked to me yet, but they call me to look at them. I think that’s one simple way that I’ve learned to be spiritual in a way that makes sense for myself.

Angelia: I get what you’re saying, about how being open, maybe, is part of that spirituality, or communing with nature. When you talk about foraging I thought about the forest bathing also, that’s quite trendy nowadays. Serina, do you have anything to add to this question?

Serina: I echo what Esther said. And I love nor’s approach. I never knew foraging was illegal in Singapore. But I think the question that came in also demonstrates how...if we talk about shamanism, or animism, or paganism, the labels are derogatory to an extent. Because with, no offense, organised religion–we see this as primitive, backward, and to engage in this is not being civilised. And I think this is sad. I’m all for traditional knowledge, traditional practices, traditional engagements with nature. It has to be said, however, that not all indigenous people, not all traditional peoples are pure and perfect and kind. But I think to some extent, a large extent, that their engagement with nature is a pathway that we need to re-find.

If you look at wicca as a practice, people, whether by sea or land, they are very engaged with nature, and their surroundings. And that is also something they always connect to the female. Because of that bond with what is natural, because of the ability to procreate etc. So I think if we’re talking on ecofeminist terms, then re-finding that natural closeness to nature is essential for us to save the planet, for us to do more to combat climate change. More and more as we become more developed, more civilised, as we engage with capitalism, as nor said, we lose that. I think I see that in Singapore, where everybody’s so comfortable, and in air conditioning. We forget that Singapore is an island, and we have sea all around us, and there (are) pockets of nature that we can go out and touch and feel. Most people don’t want to step on grass. And don’t want to walk on a trail that doesn’t have tar.

That means we’ve lost that connection. So I think re-finding that connection can go a long way in helping solve all the problems that we have.

Serina: Thanks very much Serina. I really hear you when you say that we should validate indigenous knowledge that traditionally has been dismissed, but at the same time not overly romanticise that as well–I totally agree with you on that score. I also wanted to say something–I suddenly remembered, what nor was saying about knowing the names of things. We have an essay in our collection also about learning the names of birds, so I thought that was very timely you mentioned that.

Perhaps back to that whole idea of self care and taking time for ourselves – one of the things that we can also do is perhaps equip ourselves with more knowledge about our natural surroundings and the environment. Perhaps most of us in Singapore never go beyond primary or secondary school science in knowing the names of things around us.

One of the things that perhaps we could do as individuals–no need to rely on the state or government for that– is to empower ourselves by knowing more. Taking that first step to know our environment better.

Esther, I think there’s one last question that has to do with our editing. So I thought maybe we could take that: The topics of the essays are very varied, and what were some of the challenges in choosing essays, having to decide what counts as ecofeminism or what doesn’t?

Esther: So it is true that the essays, the topics are quite broad. When Angelia and I were working on the brief for the open call, we were very clear that we wanted to be as inclusive as possible. We also wanted to include stories whereby the contributors themselves, maybe they were not aware that oh, what I’m doing is actually an example or manifestation of an ecofeminist practice of care, of kinship, of kin making.

So I think that’s why you’ll notice the essays really range from, let’s say, an eco-spiritual approach, for instance, to humans’ relationship with birds that inhabit the space with them, to contemplating the idea of home, a house, what it means to feel at home. And also to think about a more eco activist point of view about movement work and care. It really does show us, shows the reader as well as the contributors and us editors, that it’s all around us. In terms of the decisions we make, in terms of our everyday lived experiences, in terms of our personal lives – we can and we in fact are participating in an ecofeminist practice of care, of kinship, of reciprocity. So that was an intentional approach.

Angelia: Just to say that I agree with Esther. That was a good summary of the approach that we took. The emphasis was always on inclusivity. Wanting to hear a range of voices from all over, all different women in Singapore. I also wanted to add that I think some of the essays perhaps treat space in a more symbolic and metaphorical way. In terms of the environment, in terms of also having a mental space or the space of memory. Some essays may not directly engage with the environment or natural world but many of the other essays do.

But at the same time, I think it’s very important to recognise that space may be very real to us, even if it’s symbolic. One of the essays talks about the wilderness, but it’s very much the wilderness as a kind of symbolic metaphorical space rather than the natural kind of wilderness that most of us might assume.

So I think you will find that the essays cover a wide range of topics, ideas, issues. I hope that you’ll be able to see commonalities in terms of how everyone is advocating, in a way, caring for others, for their communities. Caring about the past, caring about marginalised views, marginalised peoples. And really asking all of us to rethink our role and our position, perhaps in Singapore, and depending on also what we do. And maybe just reflect a little bit more about that.

I think we’re nearly running out of time, so I’m going to just end our panel discussion. Thank you, Esther, nor and Serina, for joining us today. I hope we managed to give a flavour of what the collection is about to our listeners. I really am very proud of this collection, and of everyone’s essays. I can’t wait for people to actually read the essays and find out what they think. Hopefully the essays might even transform some people and what they do. Thank you everyone.

About the Speakers:

nor is a Singaporean artist whose practice is rooted in self-portraiture. Their works span the disciplines of photography, film, video, performance, text and spoken word poetry that engage with ideas of belonging and identity through frameworks of gender performance, ethnographic portraits and transnational histories.

Dr Serina Rahman is a Visiting Fellow at the ISEAS-Yusof Ishak Institute, where she examines issues of (un)sustainable development, rural politics and political ecology. She is the co-founder of Kelab Alami, a community organisation that has worked since 2008 to enable a fishing community in southwest Johor to participate in and benefit from unavoidable surrounding development and urbanisation.

About the Moderator:

Angelia Poon teaches Literature at the National Institute of Education, Nanyang Technological University. Her research interests include postcolonial theory and contemporary Anglophone literature with a focus on issues pertaining to globalization as well as gender, class, and racial subjectivities. She co-edited Singapore Literature and Culture: Current Directions in Local and Global Contexts (Routledge, 2017) and Writing Singapore: An Historical Anthology of Singapore Literature (NUS Press, 2009). A firm supporter of Literature in schools, she has also co-edited two poetry collections for students, Little Things (Ethos Books, 2013) and Poetry Moves (Ethos Books, 2020).