"This is free verse that refuses freedom the way we see it" | Our Ultimate Wordlessness: The Enigma of Wong May's Poetry

Recording of A Bad Girl's Book of Animals Book Launch

The book launch of A Bad Girl's Book of Animals took place at Arena at 10 Square on 24 March, Friday. You can watch the recording above and access the full transcript of the programme on this page. Portions of the transcript have been edited for clarity.

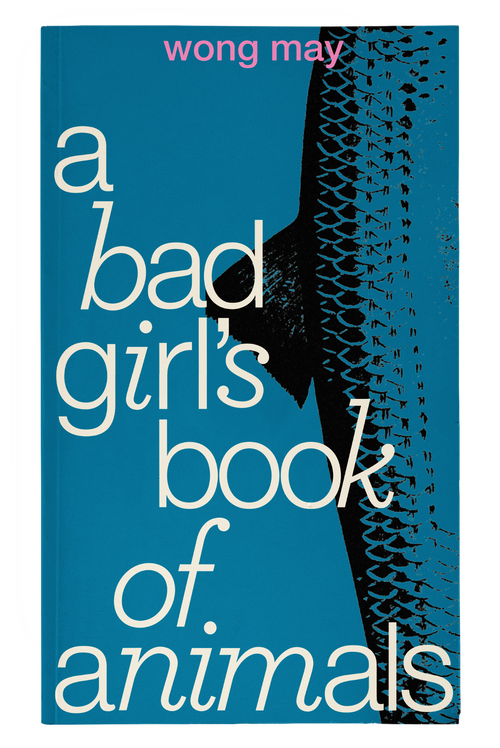

About A Bad Girl's Book of Animals:

Wong May’s poems are concerned with the ultimate loneliness, the inarticulateness and the inability to communicate fully that are the marks of human life. “My poems,” says Wong May, “are about wordlessness rather than words. I feel that we must recognize our ultimate wordlessness.”--

You can find the speaker bios at the bottom of this page. Enjoy the conversation!

Photo of speakers (background). Left to right: Jennifer Anne Champion, Ann Ang and Tse Hao Guang. First row audience members on the right

Arin: Good evening everyone and thank you for joining us at the book launch of A Bad Girl’s Book of Animals by Wong May. I am Arin from the Ethos Books team, and my pronouns are she/her. I am wearing a black top and black jeans and I will be your host for today. I would like to give a gentle reminder for everyone to wear masks in the venue today if you can, to reduce health risks for our immuno-compromised friends in the audience. We also have a photographer who is taking photos today. Please approach us after the event if you do not wish for your photo to be uploaded on social media.

Let me begin by giving thanks to those who made this event possible: to the team at 10 Square for this lovely venue, and to Equal Dreams for providing sign language interpretation for our guests here and online, and of course for our poets and panellists for joining us to celebrate Wong May.

Before I introduce our panel, let me give a brief introduction to Wong May. You may be wondering why we are having a book launch without the author here. This is because Wong May has been famously private and prefers for her work to speak for itself and she shies away from the limelight.

She also lives in Ireland with her husband and children. A Bad Girl’s Book of Animals is her first collection of poetry which was published by Harcourt Brace & World in 1969, and we are very honoured to be reissuing it and bringing Wong May’s poetry back to Singapore. Her other books include Reports (1972), Superstitions (1978), and Picasso’s Tears: Poems, 1978-2013 (Octopus Books, 2014).

Her latest work is the collection of translations, called In the Same Light: 200 Tang Poems for Our Century. In March last year, she won the Windham-Campbell Prize for Poetry. You’ll get a better sense of Wong May as a poet and her poetry when you hear our panellists discuss her poetry.

And now I’d like to take the chance to introduce our panellists.

We have Ann Ang who is a literary researcher and published writer best known as the author of Bang My Car. She published her first poetry collection, called Burning Walls for Paper Spirits in 2021. A keen birder, Ann also researches contemporary Anglophone writing from Southeast Asia and South Asia.

And we have Jennifer Anne Champion, who has published two collections of poetry and has been featured in numerous anthologies in Singapore and abroad. She is co-founder of poetry.sg and served as its multimedia editor. So currently, Jennifer’s practice is grounded in slow crafts and mindfulness. She was a digital writer-in-residence with the National Centre for Writing (UK) for her work in poetry and textiles. Her poetry and textile works have also been on display with Art Outreach Singapore and NUS EMCC.

And we have our moderator and editor of this collection – Tse Hao Guang is the author of The International Left-Hand Calligraphy Association (Tinfish Press, 2023) and Deeds of Light (Math Paper Press, 2015), the latter shortlisted for the Singapore Literature Prize. And apart from A Bad Girl’s Book of Animals, he’s also edited the anthologies such as Food Republic (Landmark Books, 2021) and UnFree Verse (Ethos Books, 2017), and he is also the editor of the e-journal OF ZOOS. Poems and essays appear in Poetry, Poem-a-Day, The Yale Review, Poetry Northwest, Entropy and elsewhere.

Hao Guang will be moderating the session for us today. We will begin with opening remarks, followed by a 40 minute reading and post reading conversation with the panel. We will then move into Q&A for the last 15 minutes of the event.

Without further ado, over to you Hao Guang!

Hao Guang: Thank you. So I just want to thank Arin for that lovely introduction. Thank you also to everyone at Ethos for bringing this book to life—to re-life, to resurrect this book. For a long time, I wasn’t sure any publisher would ever be willing to take on this book at all. There is a measure of foolishness inherent in writing and publishing any kind of poetry today, much less any kind of poetry Wong May has written. And so Ethos has agreed to my foolishness, and said okay to my foolishness. It gives all of us, including those who write poetry, hope. In the sense that even if our voices go out fashion, or they’re not heard anymore for many many years, the chance remains for our voices to come back to life.

That’s what part of what this book means to me at least.

I hope that our encounters with this book – as we read it, as it is encountered by the general reading public, will change how we see and receive things that don’t easily fit in. That it will enlarge what we expect to feel or think about poetry, about Singapore poetry. And it will also help us to learn from an artist, Wong May, who keeps telling us not to look at her, but her words instead.

I hope that this excitement around Wong May’s republication will snowball and lead to opportunities for her next two early books –Reports and Superstitions to be republished as well.

I remain certain that this will happen, it's just a matter of when. That is pretty much what I wanted to say. And what I want to do is to move on to the poems themselves.

Maybe Ann could read first? And then I will go next, and then Jennifer the third, in order of reading. Mostly Because Jen has a special… exciting presentation.

Jennifer: Now you’ve over-hyped it!

Hao Guang: I’m excited!

Jennifer: Temper your expectations…

Hao Guang: Maybe Ann first.

Ann: So I’ll go first. And the poems I’m reading are fittingly the first two poems in the book to give everyone a flavour of it:

On his 23rd Birthday

In his country they use water-

hyacinths to feed pigs. Imagine

the stuff pigs are made of!

He lies in bed thinking this

is but a zone of his life—

As if life has zones!

The purple flood! That is, if

Consciousness is

in streams.

He gets up,

eats a can of sardines

& buries himself. He knows

himself too well already,

he hears his voice

in another country,

softly. Women

would say: After

all these years,

You haven’t changed

a bit!

The telephone rings.

History

The lie that snow was here yesterday

up to my very door. The lie that

though a brief thing it was,

It was. The lie then

I’ve got a mother

I’ve committed murder

I’ve recovered

I couldn’t have wakened

to a finer world.

I carry you with me now

child and mother

(the weight of snow) sleep

walking down the steps

across the street

It is October 1967

everywhere this sun and water

we’re going steadilier

steadilier immortal

Ann: And that’s it!

Hao Guang: Thanks Ann! I’m going to read from "Dialogue". I’m jumping all over the place. So in the new edition is page 41, for those who have the book.

Dialogue

said the moon at 4 O’Clock

have you ever been loved

by a woman, armless?

But love, love is armless.

Form is a bottle of bones

Form pure, incorruptible.

Flesh,

the jelly where flies

die! My fingers lie

against the cool glass

of window, of mirror,

pink, curled, gentle

like shelled shrimps. Flesh

itself died

in the bottle, is preserved

in the form of a bottle.

I offer

you this: a room.

Love is

a room you said. Yours.

Honey in my eyes

Honey

trickles from my ears!

The sun

itself

would have come in

had it not been

a sun, terrified.

HG: The next one is Concordance, on page 76.

And I like this because Ann was saying Wong May seems to be laughing a lot in her poetry. She’s laughing here.

Concordance

He grows pale, seeing that she cannot.

Her way of paling is to laugh

like bottles jostling against one

another in water

in perfect emptiness

ringing clear like a thrush

She grows pale, seeing that he cannot.

His way of paling is to look

literally like a peeled onion

She rings and rings and tilts her head

till tears gather in her eyes.

Lacking,

He finds himself on the brim

waiting

Hao Guang: And the last one, the second last poem of the book, It’s called “Remember”, on page 120.

Remember

Remember my right hand to your right hand

Remember my eye to your eye

Remember what I could not have

to what you have kept

Remember the symmetry the beauty

where exactly we cut ourselves

into two halves of a peach

of a fish

Remember my flesh to your flesh

all our pores listening like muffled ears

Remember to each our essential selfishness

the bridge that isn’t anywhere

Remember my breath to your breath

for no reason this rhythm

this perfection

HG: Alright.

[Applause]

Jennifer: I’m going to read a poem first. So this poem is called "Narration", and it’s on page 45.

Narration

All my beautiful young men going

down the drain: the bats, trout,

goats, the grinder-sink

gargles: forwarding address

not for deposit of mail.

I’ve spent the whole summer

in the animal hospital,

myself recovering to them,

myself recovering fur, fin,

fangs, claws. All my

beautiful young parts

dance together

go swish-swash-swoop

down the drain: the reason

for wasting so much good whisky.

This is a way of telling a story:

Wash it down your throat.

Jennifer: What happened was, this morning I woke up and flipped through the book and came upon the poem called "Song". And I don’t know why… I just felt it would be nice, in honor of Wong May, to make her "Song" a song! So that is what I have done. I’m gonna need some audience participation. Okay?

I’m going to be making some animal sounds during the song performance, and if you could also make some animal sounds with me, whatever secret animal is inside you, that wants to make a sound, you can make a sound.

Okay? Alright! This could go really badly… Okay!

Do you want to practise actually making the sounds?

Audience: Yeah!

Jennifer: I do this with my poetry students, my younger ones. I tell them to make an alien sound that comes from their chest in response to a question. So Hao Guang, ask me how am I doing today.

Hao Guang: How are you doing today?

Jennifer Anne Champion

Jennifer: [Inaudible guttural sound] So that’s the kind of sound that you can make. Don’t worry about whether it makes sense or not. I believe that poets are very interested in sound, and even though there’s no word attached, because Wong May has been spoken of as a poet who has an enigmatic wordlessness.. I think she would appreciate having these sounds form her “Song”. Okay, alright, let’s go!

Jennifer: [plays guitar, sings a musical howl] Y’all are leaving me alone on this, are you?

[audience makes animal sounds]

Jennifer: Love it. Thank you. [sings Wong May poem] Thank you so much. Alright, while I have the guitar here, I’m gonna try another one. I have no idea how Wong May is going to feel about this honestly!

Hao Guang: I’m sure she’ll love it!

Jennifer: Yeah? I hope so, I really do. This is completely improvised, it is a poem I promised to read which is called “Shadow”.

Shadow

Your shadow tells me

you are not doing this. Do

I trust you. What

do you think you are

doing. Just how

unhappy

or happy do you

want yourself to

be. (and me)

I want to be

that wall where

your shadow tells me

you are not doing this

Jennifer: Thank you!

[Applause]

Jennifer: You can have your mics back now.

Hao Guang: Maybe we should skip the Q&A and just have Jen sing the rest of the evening.

Jennifer: I’m not prepared for that.

Hao Guang: This next part is a little dialogue, we have prepared some questions for Ann and Jen. These are questions I pose to readers. If you’ve read the poems before, feel free to answer as well.

This is the first establishing question.

When did you first encounter Wong May's poetry, especially this book, A Bad Girl's Book of Animals? And what has it meant—how did it make you feel? The context of this is that this is a book that was first published in 1969, right. I’m not sure how many of us in this room know about that era first hand?

Ann: So I first encountered Wong May about two years ago. And I was very fortunate that the university I worked at actually had the first edition, the 1969 version of it.

The reason why I encountered Wong May was that she had been making a bit of news with the Windham Campbell prize and also a new book of translations of Tang poetry. But I also found out at some point that she spent quite a bit of time in Singapore, at least at the start of her career.

So I asked why have I not heard of this Singapore poet before? This so called “Singapore” poet? And she is a poet that challenges us to expand our idea of what Singapore is beyond a sort of national framework.

But when I read her poetry, that was not something I actually had in mind. Because it’s like nothing I have ever read before.

You think it would be part of tradition, you think you could easily relate it to some sort of “national” tradition. But no, it’s nothing like that at all. And it has a radical simplicity.

So when I read it they’re like nursery rhymes turned inside out, and I didn’t think they were from the 1960s at all. Which is the challenge that poetry issues to us: that it doesn’t have to be of a place and time and yet could still be read in relation to that place or time as well.

I think encountering Wong May is a sort of broader encounter with poetry. It changed my life about what it could be like.

Jennifer: I came across A Bad Girl's Book of Animals two years ago as well. Ethos is not gonna like it but I got it as a bootleg copy so I didn’t have a physical copy of the book. It was sent to me but I was reading it at the point where I was on residency working on textiles and poetry. At the same time, I was encountering another person named Lorina Bulwer. Lorina Bulwer was an inmate, in an English asylum, in the late 1800s who wrote long streams of consciousness, words, letters, basically, to anyone and no one, to everyone in her town and how much she hated them.

The contrast between this massive amount of endless flowing words versus Wong May’s very tight and deliberate use of words. It struck me that there was a similar kind of irritation with society that I could see in Wong May’s book and also in Lorina Bulwer’s samplers. And it was just very interesting to me that both women separated by time, culture, aesthetics even, were still writing from the same place.

Hao Guang: I think the next question leads from the title of this event, which is wordlessness. Basically Wong May has described her own work, A Bad Girl's Book of Animals, as a book about wordlessness. Many others have also called it also a book about loneliness. I have seen some recent reviews of the book after its republication echoing that same sort of sentiment, they agree that it's about wordlessness, about loneliness.

I wanted to ask you guys what you thought about that, whether you accept it or whether you push back against it? And something new which I haven’t discussed: my instinct is to push back a little bit on that, and part of that has to do with an issue of gender. The question of what is a woman is expected to do or appear like.

Is a woman expected to be wordless and silent? At least in the 1960s? Maybe you guys could think about, in relation to that, what do you think about this characterisation of her poetry and her work?

Ann: I mean my first instinct is to push back also, and actually to push back against the last idea that Wong May is about wordlessness and lostness. I actually think that the spareness of her poetry is where the potency is. And it is true that in this collection there are quite a few speakers who come from quite judgmental families, in that sense. I think I used the word “unsparing” just now.

But I think the lostness is not a negative, it’s not a lack. The wordlessness is the silence and empty space around the words, but it’s still speaking as part of the poem. She’s made it with those few words. She’s charged the entire page to be part of the poem, a sort of electricity to things.

I don’t think it necessarily has to do with gender, I think it’s just Wong May as a poet. I think we can give her that claim to universality as well, beyond these identities categories, at least that’s my way of pushing outwards instead of pushing back.

Jennifer: I would say, to finetune the gender aspect, Wong May is writing about gender roles in the book. But I don’t think that she is necessarily saying my perspective is mine because I am a woman. In fact she is sort of rebelling against these strictures of what a man should be and what woman should be.

With regards to loneliness, I think there is a distinction between being alone and being lonely. I don’t know if I necessarily get the sense that Wong May felt lonely when writing this. There are deep, deep waters running in the stillness in which she was producing this work. And Lorina Bulwer as well. Which is why I mention that immediately I connected the two, because both are writing in isolation.

Hao Guang: This leads me to the third and final preset question. You know now that the book has come back to life, has been republished, it’s now reaching—at least I hope it will reach—a younger generation, many younger generations, right, since the 1960s.

How would you guys frame Wong May for an audience today who may or may not be familiar with Singapore poetry? Perhaps they are familiar with poetry, but maybe not Singapore poetry. How do you find her concerns and themes, her styles speaking to us today?

Jennifer: I don’t think she is as concerned as contemporary poets and readers are about being “Singaporean enough.” I don’t see that anxiety at all in this book. And I like that. Especially when there is a way young poets nowadays write about the “Singapore poem”, or the writing as “The Singaporean experiencing life elsewhere”, that is very instantly recognisable and for me personally a little bit annoying. But when I see Wong May talking about American life, or home life, wherever home manifests for her, I don’t feel so “judge-y”, if that makes sense.

Ann: Just adding to that, the way I would introduce Wong May to audiences who are not so familiar with her, would not start with the Singapore angle because I agree with Jen; it’s not about location, it’s not about any straightforward sort of pigeonholing of experiences. I would invite new audiences by saying: this is free verse that refuses freedom the way we see it, but uses constraint to make a poem out of it. It’s readjusting your sense of what free verse might be. And if we’re going to think about looking at Wong May in relation to other poets, then she has a closer relation to some of the American modernists as well, and one other poet she has quite a close relationship with is Hilda Morley who is one of the Black Mountain poets. And just reading across spaces, but together with form, is one thing I would invite audiences to do, and to not think in national categories or even those lines of tradition but to think what form can offer us across those lines.

Hao Guang: Now is a good time to to open up the floor to any questions you guys might have.

Question: I would love to hear the three of you respond to the difficulty of Wong May’s poems. Cause actually, if you open it up and read it, the lines are running in very unusual ways.

There’s also brackets, unended lines, there’s no fullstops sometimes. Things like that. Because maybe all of you already have become familiar with this world that she brings you into. So for a reader who is fresh to Wong May – even a poetry reader, because as you say, poetry runs in very familiar ways sometimes in Singapore context.

How did you first respond to this strangeness and how would you lend a hand to people getting used to this strangeness?

Ann: I would point to the visuality of it. I would say this is an Insta poem, just to be annoying. I would ask [them to] look at this, and maybe say, this might look like an Insta poem but it’s not like it at all.

Maybe I won’t even say it’s a poem. Just read it as it is, because the lines suggest that you can. You don’t need that definition, that predetermined category of poetry to read it. I think I’d just get someone to just read it, if that’s still possible nowadays!

Hao Guang: I would approach it as I would encourage people to approach any poem, which is the opposite of a close reading paradigm that you might do if you are encountering it in a classroom, and you have to write an essay about it.

So don’t actually worry about what the poem means. Let it flow through you. And let yourself feel what the poem wants you to feel. I think that’s a good way to approach any sort of poetry.

Especially the kind that is quote-unquote 'difficult’. And I hesitate to agree with the word ‘difficult’. Maybe strange, I do agree with. But difficult, not so.

Jennifer: Yeah, I was trying to look through the contents to see what poem I would recommend to a fresh reader of poetry. But I realise it's very hard to pick one, because it's as if Wong May has a poem for every situation, but not a poem for every situation at once. Does that make sense? [Chuckles]

But I would say, on the base level, Wong May is an excellent poet because she grasps that you need to be as powerful as you can possibly be in a very small space. Every single word in there, [having] no punctuation, [having] line breaks in very strange places.

When I sang the version of “Song”, I changed her line breaks to make it more song-like. And yet I assume from the title, that this was an attempt at a song. The way she thinks is very different and very original.

And there is something so lovable about that. I think the only way to really understand, to borrow from Ann’s (response) just now, the only way to understand Wong May is really to just read her. Full-stop.

Question: Thank you. As practising poets yourselves what I’m curious to know is, do you guys feel like you’ve learned anything from reading her? Are there any specific examples from her poetry that have led you to some sort of conclusion or realisation about your practice as poets?

Jennifer: Okay. I'm gonna get personal. This book of poems came to me at a time when I thought that I should do my duty as a Singaporean and settle down, get married, and be like, housewife type of person.

A lot of the poems in Wong May’s book are about poking fun at that. And wondering to yourself, “Am I a proper woman or not?” “Is this person a proper man or not?” And what does that mean? Do I care?

So it’s not so much learning, but I felt that my own ideas, my own disdain for all these gender roles – I felt supported by reading her poems. I felt reinforced in my own idea that it’s all a little bit bullshit.

Ann: Like Jen, it’s also a personal thing to talk about my creative practice, and I think last year was a personally difficult time because my mum passed very suddenly. Wong May talks a lot about her mum in her poems. Not just in this book, but in her successive books as well, Reports and Superstitions.

For the longest time I couldn’t write. Because everything seemed to have been clogged up. But I think somewhat earlier this year I was doing some research work on Wong May, so I was just reading her from a academic angle. And the thing I noticed about her poems is that there is this intense grounding in the body. And you see some of that in this book as well. She talks about the pores of the body, and in another poem—in one of her other collections—the pores of the body become the eyes of the body. And you feel like the spirit and flesh are the same kind, in a very organic, biological way, in a way that transcends that as well. A little earlier this year I was rereading her work again after the research had been done. And I started to write again, because just looking at her poems I felt my own words responding to that very corporeal dimension of her work as well. So yeah, I have to thank Wong May for that. But I know she’s not just that single individual, she’s in every one of her poems, she’s wherever her words are read as well, and I have to give thanks to that.

Hao Guang: You asked a very difficult question. Maybe for some context I released a book of poetry recently. That book took about seven years to write, since 2016. That was maybe three years after I encountered Wong May’s work. The encounter with it shattered me in a way. It renovated my understanding of what poetry could be.

It renovated, also, the ways in which I thought about myself as an artist. Given that she as an artist figure is so conflicted about putting herself out there, about selling her own work, promoting her own work, publishing her own work, even.

It didn’t really fully click for me until I started thinking about what I wanted to do for my next book.

It just so happened that when I started writing my next book, it just was very different. Ann says she thinks that my new book is Wong May-ish, but then after thinking more she said she disagrees.

And I wasn’t looking to Wong May specifically or any particular poem in writing it.

I think I was able to be freer. To take myself less seriously, to not worry so much about, like, “oh am I writing an important or good poem”, and just write. I think it has allowed me to be a better poet, and it has allowed me to let myself get out of my way of my writing. I think I am a better poet and person for it.

Question: Hi. To be honest I know very little about Wong May. I’m just wondering, just based on her age, whether she made a lot of connections while she was studying at the university here, with the other older poets whom we know more of today. I believe she is maybe a year older than Arthur Yap, whether they know of one another or might have interacted with one another. And whether if you feel that there’s maybe a little bit of Arthur Yap’s influence in Wong May’s poems?

Hao Guang: I’ll take this one! [Laughs] I wrote this foreword in the midst, as part of doing this I had to dig through any reviews to find out about her work. Arthur Yap reviewed Wong May’s work. The context is Wong May and Arthur Yap were contemporaries at the University of Singapore, they knew each other, they probably read each other's work, even at that point before Wong May had published books. And also (Edwin) Thumboo definitely knew about her.

He anthologised some of her early University of Singapore writing in volumes like The Second Tongue as well as in Seven Poets I think. But he tended to favour those poems that she wrote while still at the University of Singapore. After she left for the US, and started publishing these books, I think he didn’t think they were suitable enough for some of the other anthologies he was doing.

She was known and she was read but there was always an uneasy sort of acceptance. Not full acceptance of her as a writer. I think part of it is that people thought she was away and clearly influenced by a lot of American contemporary poetry at the time, so the lineage to Singapore poetry felt weaker. That seems to be how people thought about her work.

A fair number of academics over the years have examined her work – Koh Tai Ann, Shirley Lim, they have all looked at her work in relation to other work that was going on at the time.

Ann: I mean it’s not a direct relation but it's also interesting to consider that both Arthur Yap and Wong May paint as well. And I’m wondering whether that connection between the visual and the poetic has something to do with their poetics more generally as well. I don’t think anyone has done a comparative study between the two poets yet.

Hao Guang: I've only seen one painting of Wong May’s. And that was because she was interviewed in The Irish Times and they had a picture of it, but I can’t find any of her paintings online otherwise. So I don’t know what she paints.

Ann: She paints under a pseudonym, also.

Hao Guang: Ya she uses a different name when she paints.

Question: I don’t know Wong May at all, but when you talk about painting and poetry, I'm asking from your own perspective, do you think you would approach poetry very differently if you also painted as a pursuit?

Hao Guang: I want to arrow Jennifer. Because although she doesn’t paint, she does visual art broadly speaking.

Jennifer: My personal opinion is that to be a good poet, is actually to have at least an interest in all the other art forms. Because poetry, compared to other forms of writing, takes into consideration the visual. The space and the placement of words. It also takes into consideration sound, so the audio aspects of sibilance, assonance, all that sort of thing.

I feel like I’m going to offend a lot of poets when I say this. I think the kind of poet who says I only write poetry, I’m only interested in words, I’m only interested in this art form, I’m blinkered to all other art forms, is seriously losing out in terms of making their poetry richer. Yes.

To tie it back to Wong May, I didn’t know that Wong May was a painter. Since there are two poems in here actually called “Song”—one is called “Song” and another’s called “Spring Song”—I would have thought maybe she wanted to be a rockstar at some point in her life.

Ann: Maybe she wants to be all three.

Hao Guang: Then she’ll have a third name.

Ann: I think it’s a really interesting question, whether painting allows you to see different planes. If you’re writing about the same subject, and painting about the same subject, whether the two are speaking to each other. I’ve never done that myself, so I don’t think I can speak from personal experience but I can see how that might work for Wong May who was very much influenced by the expressionist. Her last collection Picasso’s Tears is an obvious pointing in that direction for consideration as well. So her later poems are even richer. In terms of the way they refract perspectives, [they] are even more extensive and more ambitious than what we see in this book. So definitely for Wong May, that seems to have been an essential part of her practice.

Hao Guang: What I would say is that I’ve never known any poet who hasn’t been interested in other art forms. Even if it’s not to do it, but just to appreciate or consume it. As a roundabout way of answering your question, my latest book is very indebted to the visual arts. Part of it is because I have a friend Ivan, who’s a really good painter, a really good visual artist actually. He does collage work, and I was very fortunate to be in his studio, observing him do his work. I found a lot of resonances with the way that I write my own work.

He is a collage artist so he has a trash heap in the corner of his studio, where he has put discarded scraps of things he’s printed out, newspapers, even old work that he has pulled apart and thrown into the trash heap. He takes bits of it, puts it up, and tears it off, so that it leaves a trace of the tear behind, paints over it, that kind of thing. To me it felt like how I was working with poetry: quoting, deleting things, taking from different sources.

And I feel like maybe Wong May—I mean I don’t know anything about Wong May’s process at all—but I think some of the ways that she uses images, turns of phrase, feel like a similar process perhaps, of taking different times, different areas, and smashing them into a startling and surprising relation. I’m not sure if that answers your question, but this is what came to mind.

Audience: Thank you for sharing, all three of you. Can I ask another question? You mentioned Picasso’s Tears, and some of her books are really hard to get in Singapore, so I’ve not read a lot of the other books. Can you make a comparison between the writing style in the latest collection of poetry as compared to this first book of poems?

Hao Guang: I don't have an answer prepared, so I’m just gonna say what comes to mind. I feel that A Bad Girl’s Book of Animals is also in part a response to the Iowa style or Iowa approach to writing. So the backdrop of this is that she left Singapore and moved to Iowa city, where they had, if I’m not wrong, the first MFA or Masters in Fine art in creative writing. She enrolled in that programme.

Part of the approach to this is that they take the poem or short story as something like a chair, like a piece of furniture. And everyone comes into the workshop to work on the piece of furniture together, to scrape it off or do things with it.

They have this workshop model. And I feel that Wong May didn’t fully accept that way of doing things. I will read you the last poem. I will explain why I say what I say. It’s called “A Lesson”.

And if you are familiar with some of the things people say in creative writing workshops you will understand what I mean.

A Lesson

Extinguish fox eyes.

Extinguish violets. We will have

no leaves, no dead roots

for this autumn,

no God

walks the mauve hills: The air

at this moment

is saying

just this.

* * *

There’s a justice in this.

Say it.

A purity. The stars kill

each other with it.

Nightly. I think it

can be done. I want

a man

to judge

without being unjust.

Describe winter, I say

without snow, or cold,

or North. Use

no white for white.

He says, it

cannot be done,

But it is given,

(and mostly as punishment).

Hao Guang: Okay, so in creative writing shops, sometimes people will say, I want you to write about winter, but you cannot use the words “snow”, “cold”, “white”, that kind of thing.

They call it “show don’t tell”. I think this poem is a way of pushing back against that. This book would have been very likely developed as part of the thesis for her MFA. So I just want to say that this is her – the book where the poems were the shortest, and most compressed.

Actually as she publishes, and as we get to Picasso’s Tears, the poems become very, very long. There’s an enormous kind of freely moving—so “Picasso’s Tears”, the poem, is like a book length poem all on its own. It takes up like thirty pages in the book Picasso’s Tears, and is essentially about Guernica, or the monumental painting that he did about the war. So to me she has developed in a way that shows that she is rebelling against this idea of the short compressed lyric.

What else can I say? I think she has become more European, maybe. This is probably because she moved—my bias because she lived in Europe and settled in Dublin where she still lives today.

She has said for herself in an interview if she had stayed on in the US, she would have progressed very differently as a poet, but then she moved to Europe. So to me that is part of it.

Some of the references, the kind of figures that she looks to become a bit more European. Like Paul Celan, and suddenly you have all these European writers she increasingly looks to and essentially namedrops them in an interview at the end of the book Picasso’s Tears.

Ann: I thought I would say a little bit about Reports and Superstitions. It’s the in-between books between A Bad Girl’s Book of Animals and Picasso’s Tears. In those collections, you can see her responding quite clearly to the big events in the day. So “East Bengal” is a poem that responds to the famine in Bengal in the 1960s, and she also talks indirectly about the Vietnam War. So sometimes I think Wong May is read as a poet simply as a poet, but she is very much engaged with these issues on her own terms in her poetics as well. She has travel poems, but not in that direct way as well. I think it’s in Superstitions. You have perhaps one of only two directly Singapore-referencing poems, which is “Kampong Bahru, 1975”. But it occurs in a long string of travel poems as well. So she does get more place-specific in her middle collections too. So too is Picasso’s Tears, more European, more ambitious.

She also has a series called “Wannasee”, based in Germany, written in Germany. Again, it’s a fifteen-part poem, so you can see her poems getting longer. I think she’s experimenting quite clearly with what a poem is, refusing the page as the unit of a poem. Very exciting.

Jennifer: I have only read this book, A Bad Girl’s Book of Animals, and you should read it too!

Arin: Do we have any last questions? Even from the panellists as well, if you have any questions for each other?

Ann: I want to ask Hao Guang this question, because he mentioned it just over dinner, that Wong May described this republication of her first book as a sort of homecoming, or it would assuage her homesickness. Would you like to say a bit more about that?

Hao Guang: This is actually Arin’s story originally. Because Ethos—or Arin—wrote to Wong May to ask her to get her contract signed and everything. When she replied positively, she said—maybe I’m not quoting her exactly—but she said something like, “I’m glad that Ethos and Hao Guang are willing to take this up. To me it sort of assuages my homesickness for Singapore.”

There are many things to say about this. I think the first thing that came to mind is a bit of sadness, because clearly the Singapore that she’s homesick for doesn’t exist anymore. And maybe that’s also why she doesn’t come back to Singapore, right. That’s part of it, but also to me, she did care for the book to be read by Singaporeans. Even though we keep saying, don’t lump her in this box. She actively wanted this book to come out, and it meant something to her that it came out from a Singapore press.

To me it was a sign, that it was a positive affirmation of this publication, it wasn’t just oh, if you like it, you should just go and do it, you know what I mean? So she was actively saying, yes I would like for this to happen.

The other part is that she also quoted T.S. Eliot, from Four Quartets I think. She said something like, “In my end is my beginning”. She is suggesting “this is the twilight of my life.” It seems that there is this new beginning with the new book being published. So that was an additional “oh!” sort of moment for me.

And I also recall her mentioning in an earlier interview, even before she had any English [education]—she grew up in a Chinese speaking household that spoke very little English—that she encountered another T.S. Eliot poem. Perhaps it was also Four Quartets? I think it’s the one with the lady of silences so, yes, it’s Four Quartets. so she encountered the lady of silences in T.S. Eliot’s poem and felt enchanted by it, and the fact that she returned to Eliot with that quote felt like it meant something, although I don’t know if she was actively thinking about it.

Arin: If there are no last questions, or if you would like to speak to the speakers after this, you can ask them directly as well. Thank you so much to our wonderful speakers.

About the Speakers:

Ann Ang is a literature educator and published writer best known as the author of Bang My Car (Math Paper Press, 2012). She is the co-editor of the literary anthologies Poetry Moves (2020) and Food Republic (2020), and also the coordinating editor of PR&TA (Practice, Research & Tangential Activities) a new peer-reviewed journal of creative theory and practice in Southeast Asia. A keen birder, Ann also researches contemporary Anglophone writing from Southeast Asia and South Asia.

Jennifer Anne Champion has published two collections of poetry and has been featured in numerous anthologies in Singapore and abroad. She is co-founder of poetry.sg and served as its multimedia editor. Currently, Jennifer’s practice is grounded in slow crafts and mindfulness. She was a digital writer-in-residence with the National Centre for Writing (UK) for her work in poetry and textiles. Her poetry and textile works have also been on display with Art Outreach Singapore and NUS EMCC.

--

About the moderator:

Tse Hao Guang was assembled with parts from Hong Kong and Malaysia. His first full-length poetry collection, Deeds of Light (Math Paper Press, 2015), was shortlisted for the 2016 Singapore Literature Prize. He co-edits the cross-genre, collaborative journal OF ZOOS, and serves as the critical essays editor of poetry.sg. He is a 2016 fellow of the University of Iowa’s International Writing Program.