"If we think of ourselves as implicated subjects, it’s really difficult to look away" : Picking off new shoots will not stop the spring book launch

Livestream of Picking off new shoots will not stop the spring

The book launch of Picking off new shoots will not stop the spring was livestreamed on YouTube on 18 February 2022. You can watch the livestream above and access the full transcript of the programme on this page. Portions of the transcript have been edited for clarity.

--

About Picking off new shoots will not stop the spring

Fallen innocents on blood-stained streets. The defiant banging of pots and pans echoing in the darkness. The birth of a springtime revolution amidst the interrupted lives of a country and its people. On the morning of 1 February 2021, a coup d’état was initiated by the Tatmadaw, Myanmar’s military, effectively overthrowing the democratically elected members of the country’s ruling party, the National League for Democracy, and casting Myanmar into chaos.

This volume collects the poetry and prose of the many writers, cultural figures, and everyday people on the ground in Myanmar’s urban centres, rural countryside and in the diaspora, as they document, memorialize, or merely try to come to grips with the violence and traumas unfolding before their eyes. Written in English or translated from the original Burmese the collection includes some of Myanmar’s most important contemporary authors and dissidents, such as Ma Thida, Nyipulay and K Za Win, as well as up and coming authors and poets from all over Myanmar, reflecting the country’s rich cultural and ethnic diversity.

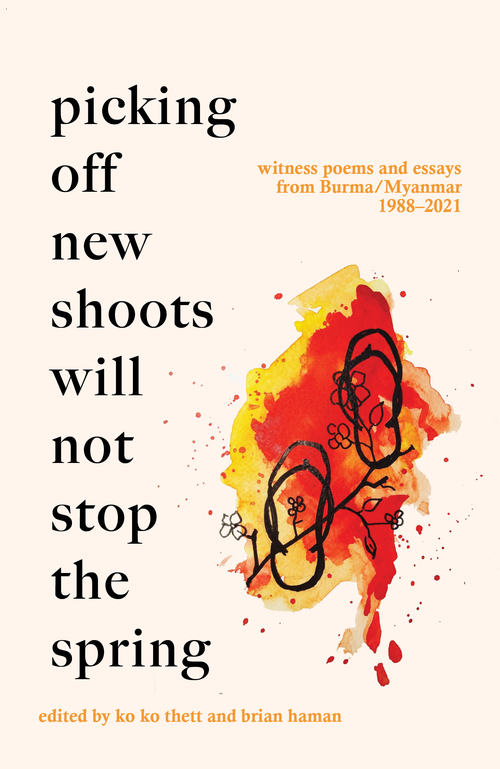

Photo of the speakers: (top to bottom, left to right) Daryl Lim Wei Jie, Ko Ko Thett, Brian Haman, Nandar

Kah Gay: It is 7.30PM in Singapore, 6.30PM in Thailand, 11.30AM in the UK and 12.30PM in Vienna. I’m Kah Gay of Ethos Books. Thank you for joining us. My wish is for you to feel, during this launch, the significance of Picking Off New Shoots Will Not Stop the Spring. Your attention honours the people who have made it possible. On 1 February 2021, the Myanmar military staged their coup. By 15 February, the editors Brian Haman and Ko Ko Thett had already reached out to Ethos Books; we took on the responsibility of publishing this title in March. Later in the year, we invited and were joined by ally publishers Balestier Press and Gaudy Boy.

The exceptional power in this book comes from the people whose writings have been compiled and edited by Ko Ko and Brian. Some of them were killed by the junta during anti-coup protests. Their experiences stay with us, and in reading them, we remember their lives.

Collective memory is one way to resist the disappearance of lives cancelled by violence. Regardless of borders and nationalities, we can contribute to this collective memory, and support the Myanmar people with our awareness and compassion.

Our memory of the writers will now be shaped by the form and beauty of the writing in this book. This is an English edition; may we see future editions spring forth in different languages across even more countries.

I am grateful for the availability of Nandar, one of the contributing writers, Brian and Ko Ko, the editors, our moderator Daryl Lim, and am looking forward to their conversation. Over to you Daryl.

Daryl: Thanks very much for that wonderful introduction Kah Gay. I’m Daryl Lim, I’m a poet from Singapore as you’ve heard, and it’s my honour to moderate the launch of Picking off new shoots will not stop the spring, which I think is a vital and landmark anthology of poetry and writing from Myanmar/Burma, and an urgently needed one.

Maybe I can start off with just a few words about the book and in some ways my own relationship to this anthology. When I was first asked by Ethos to moderate this launch, I gladly agreed and received the volume in PDF. I read it in a single sitting. This is the kind of gripping book that you will read in a single sitting, because of the stories and just how haunting and evocative the volume is. So I sat with it for a while and I was reminded—and Ko Ko will know a little bit about this—of the first time I met Han Lynn, who is one of the Burmese poets in the volume, and one of his poems will be read by Ko Ko later tonight.

I met Han Lynn for the very first time when he came for the Singapore Writers’ Festival, and I was sitting right next to him, and it was pretty horrendous to find out during the events of the past year or so that he had been arrested because of his anti-coup activities.

I’m glad that he seems to be out. But it brought it home that this man, who was right next to me, and whose poetry I actually really like because I think he’s a fantastic poet, was suddenly in danger. So I think for many of us the events of the region may seem distant, many comfortable Singaporeans in their homes, everything is going well, but actually it’s really not too far away.

The cries and struggles of the Burmese people have touched a lot of our hearts and impacted us deeply, and so I thank again the editors and contributors for this important volume, and the three publishers for bringing out these voices. So let us jump to the discussion proper, and I’ll open this question first to editors Ko Ko and Brian. It’s really a very simple question: How did the anthology come about? Could you tell us more about how you put it together?

And maybe some of the questions that immediately came to me were, because both of you come from outside Myanmar, you’re not based there anymore. So what was the process of corresponding with the wider community? How challenging was it to put together and get a sense of what was happening, especially since people were being detained or even killed, tragically? So I’m going to leave it there and ask you to tell me how that process went.

Brian: Yeah, perhaps I can start with the first part of the question, and Ko Ko can pick up the second part with communicating and getting in touch with various writers. Ko Ko and I were first in touch a number of years ago, and I’m also the editor of The Shanghai Literary Review, and there was a book that came out—I think it was published originally in 2015, if I’m not mistaken, and then translated and published into English in 2017. And that book is called Hidden Words, Hidden Worlds: Contemporary short stories from Myanmar. This was a five-year project that was put together by the British Council. It’s collected writing by writers from ethnic backgrounds across Myanmar.

And it was quite an interesting multilingual creative writing project. I contacted Ko Ko because I thought he would be an excellent candidate for reviewing the book, and he kindly agreed to review it, so that was how we both came to know each other through that review process.

Shortly after, the events started to unfold in Myanmar. We both got in touch with each other. We felt this deeply—the need to try and do something about what was happening there, trying to preserve the writing that was proliferating online primarily. And one of the things that we wanted to do was really in a certain sense try and archive that writing and really preserve that writing, rather than have it disappear into the digital world.

We started to gather the writing, by reaching out to the various writers. And then it became, unfortunately, as the violence started to intensify on the part of the military, an elegy. It became many things. It became an elegy to a number of poets who tragically lost their lives, who were murdered by the military. And it also became a platform as well, for these writers within the country.

And I think I’ll let Ko Ko continue describing that whole process.

Ko Ko: Yes, in the beginning it was about preserving resistance writing that came out of Burma, usually they are on social media and diaspora journals like Momoeka, we were thinking of that.

In the beginning, Brian did a lot of groundwork too, in inviting contributors (because he is on social media and I’m not) so I’ve got to thank Brian for doing the groundwork for this. And later, of course, when my friends Khet Thi and K Za Win were murdered by—Khet Thi was murdered in May, K Za Win in March, so our resolve strengthened and we decided to make it kind of a mausoleum, this book, as you said. We found Nandar when she published an article in Index On Censorship, so we invited her as well. But in the very beginning it was mainly contributors who were associated with PEN Myanmar. We got so many contributions via PEN Myanmar.

Daryl: Okay, thanks very much. It’s always fascinating to know how these things come about, because I think so much of the events of what happened unfolded online as well in terms of the writing. I think that’s one very interesting aspect of this anthology. Maybe I’ll invite Nandar to say a little bit about how you felt when you were asked to contribute to the anthology, and sort of give a bit of reflection about the process.

Nandar: Well, honour was the first word that came to my mind. But I also thought it was such needed work to be done. Because like Ko Ko Thett and Brian mentioned, so many young people are resisting through online, through their writings and through their arts, and only very little time where we see all their works collectively in one place. This book is not just a book, you know, it’s a collective strength, and a collective resilience that Myanmar people have brought in this revolution and still carrying on. So I feel really honored to be part of this.

But also at the same time I think one of the really really great things about this collection I see is the diversity of the voices. Of all the young people and also the older generation who have gone through a coup more than once. Also diversity in ethnicity as well, like you know there were Kachin people, Shan people, Nepali, like you would not have seen Nepali people contributing in books like this in the past. That was something I was really also very impressed by the book, that Ko Ko Thett and Brian were able to bring so many diverse voices into one place, that has one main goal, which is to achieve democracy and to continue resisting the coup.

Daryl: Thanks very much, Nandar. That’s a great point and actually we’ll come to that bit about diversity and the time period a bit later, but I’m glad you brought that up now. One question I have, since we’re talking about time, is actually—I was just thinking about this today, because I saw another news article about the ongoings of ASEAN engagement with the regime. And in some ways of course the events are over but also not over, because nothing’s been resolved. One question that I have, immediately, was why come out with this volume at this point in time? Why not wait later? So maybe you can give a bit of insight into your thinking about the timing of this book.

Ko Ko: I think this moment or this movement is not just… you know, we are seeing right now, and we felt the immediacy of the moment as well as the movement in 2021. That was the major impetus behind our anthology. But then when you think of Burma/Myanmar, the coup started in 1962, and (it was) only in 2010 that we had some hint of some kind of democratic transition. By 2020 it was ended. So from 2010-2020, it was the most significant phase in recent Burmese history. So I thought that's why we have to document what's going on right now and sooner than later. Of course there’s also availability of writings and works that was not known before because of the online environment.

Daryl: Thank you Ko Ko, I think that’s a great point. Brian, do you have anything to add at this point in terms of timing?

Brian: I think in many respects the decision was made for us because of the extent to which there was this outpouring of writing. And if we think of ourselves as implicated subjects, it’s really difficult to look away, and so it’s something that we were confronted with, just because of… you know, shared some sort of solidarity and humanity and so on that we felt that we had to do something to try and… I don't want to use the word ‘help’ because it’s a bit inadequate but to try and do something about the situation, whatever that actually turns out to be.

Daryl: I think maybe to summarise, the urgency of the situation and the energy of it was in some ways so overwhelming, that the book would have come out in some form, it’s such an outpouring. I think we really feel that as we read the book, and then the way it’s structured.

I think now is a good time to do some reading from the anthology. Maybe I’ll invite Ko Ko to read poems from two contributors; Ko Ko, take it away.

Ko Ko: Well I think I would suggest Brian to read the one by Nga Ba, which is a proper beginning. “Spring” by Nga Ba. By the way Nga Ba is a very well-known poet, you might have already seen him, but he doesn’t want to use his real name, so Nga Ba is a pseudonym.

Brian: So the poem is called “Spring”, it’s obviously metaphorically appropriate but also seasonally appropriate as well.

Nga Ba, "Spring"

Spring, seized,

turned into swallows.

Swallows, caged,

turned into clamours.

Clamours, silenced,

turned into scenery.

Scenery, covered up,

turned into eyes.

Eyes, forced shut,

turned into dreams.

Dreams, denied,

turned into maps.

Maps, destroyed,

turned into memories.

Memories, deleted,

turned into roads.

Roads, blockaded,

turned into ancillary legs.

Legs, smashed,

turned into wings.

Wings, clipped,

turned into breeze.

Breeze, detained,

turned into storm.

Storm, imprisoned,

spawned a million offspring.

Those offspring are our

inbreath & outbreath—

swallows in & out of

our nostrils—

our spring

Daryl: Fantastic poem. Really quite fantastic. Ko Ko you want to read the poems as well I think maybe we can just take them together?

Ko Ko: Yes, yes. And “Spring” by Nga Ba is actually very relevant because it describes how protests were shaped by and formed in response to violent repressions. We have had several types of protests, so many ways and forms of protests in Burma in 2021. So it’s about how the spring was unstoppable. How the manifestations of protest came about due to violence and repression. I'm going to read a poem in Burmese first, by, of course, Han Lynn, one of my favourite poets. The poem is called “Elevator” and he wrote it around 2015 or 2014, I think. It’s a short poem.

Han Lynn, “Elevator”

The coffin doesn’t fit

in the elevator.

Let’s keep it vertical.

The body will

be standing.

Isn’t a coffin always

too heavy? Shall we put

this one on wheels?

A coffin pusher

wanted

in an elevator

going down

in a high-rise.

That’s in English, and may I read in Burmese as well?

Daryl: Please.

Ko Ko:

Han Lynn

ဓာတ်လှေကား

အခေါင်းကို ဓာတ်လှေကားထဲ

အလျားလိုက်ထားမရလို့

ဒေါင်လိုက်ထားကြရတော့မယ်

အလောင်းက

မတ်တပ်ဖြစ်လာမယ်

သယ်ဖို့ရွှေ့ဖ့ ို အခက်အခဲရှိလာလို့

အခေါင်းကို ဘီးတပ်ဖို့လိုလာတယ်

ဘီးတပ်အခေါင်းကိုသုံးရတော့မယ်

အခေါင်းတွန်းသူ

လိုလာတယ်

မြင့်ဘိ တိုက်ကြီးတစ်တိုက်ထဲမှာ

ဓာတ်လှေကားတစ်စင်း

ဆင်းလာနေတယ်

(translated by ko ko thett)

Daryl: Thank you very much Ko Ko, beautiful. And actually, incidentally this is not a very related reflection, but it struck me when I read Han Lynn’s poem. There’s a Singaporean playwright who wrote a play about “the coffin is too big for the hole”. In similar ways this poem reminds me of it; it also makes fun of the state, the roles of the state, and I see a similar spirit in Han Lynn’s poem.

The second question that came to me, and it’s quite obvious immediately in the title of the book, is that although some of the publicity about the book talks about the events of last year and the more immediate coup, it actually traces all the way back to the 8888 uprising. And so actually, as you read the book, it excavates a much longer history of, I would say, protest poetry, political poetry in Myanmar. And that I think is one of the most fascinating and rewarding aspects of the book.

So I want to ask about the choice of why this book curates such a long history. So that’s one question. And then also why there is this tradition of political poetry in Myanmar; maybe Ko Ko and Brian and Nandar can all comment a little bit about it. And maybe related to this question, is it right to say that history in Burma is never just history, and it’s in fact all of it is still quite alive? And I say this because one particular example that I thought to highlight was Ko Min Lu’s poem. And Ko Min Lu’s poem is actually a really old poem, it’s from 1989 or 1988, and yet because of the events of 2021, it became alive again. And so in some ways the past and the present are so intermingled that it’s like a recurring nightmare. So I wanted to ask you to comment on this historical aspect and the tradition of political poetry in Myanmar. Anyone can start.

Ko Ko: Yes, I've been saying that protest poetry or resistance poetry—at least in the Burmese language, because we have so many languages in Burma, and I can only speak for the majority Burmese language, unfortunately. And the Burmese language, the protest poetry, resistance poetry written in the Burmese language was contingent upon colonialism. Before colonial times, we didn’t have any—not even political poetry in Burma. Poetry was usually sponsored by the palace and written by monks and other elite types of poets.

So only after Burma was occupied or annexed into British India in 1885, there was an upsurge and outpouring of protest poems. Some of them were written by monks. So that tradition I think continues to this day. And of course, many poets were not just poets, they were not just armchair poets; they were at the forefront of the anti-colonialist, nationalist movements.

Take Thakin Kodaw Hmaing, he was probably the most revered nationalist poet in Burma/Myanmar. He was also a nationalist leader, although he didn’t take up arms and wasn’t into arms struggle. He was a very peaceful poet. There was Dagon Taya, also, who was a leader in the social realist movement in the 1962 regime and so on. So the poets have always been there. And the poets of Burma like Khet Thi and K Za Win, they were very influenced by those nationalists and anti-military poets.

Daryl: Thanks very much Ko Ko. Brian or Nandar, do you want to add on to that?

Brian: If I could maybe just ask Nandar a question, about how you see your work within this longer tradition of Burmese writing?

Nandar: Sure. I think I did mention this in my writing as well. Before the coup—so first I’ll answer the question about the history. It’s so true that it’s like history repeated. It was like deja vu when the coup happened and it’s like history repeated itself. The older generation specifically felt like they were reliving the pain and the suffering that they have lived through. It was a nightmare like I describe in the writing as well. And with the work that we have been doing collectively, the feminist work that we have been doing in Myanmar. What I can say is that, like Ko Ko mentioned earlier, since 2010 there were significant changes we were starting to see in terms of legality. It was a very very slow progress, I agree, but it was going somewhere.

Look at one example of how 10 years ago, when rape happened or when harassment happened, it would not have been something that people could go to the court and complain about, or have a case on. But now because of this dialogue that we have been having over the past 10, 15 years, it was going somewhere, it was opening up people’s minds to have that dialogue around human rights. You know, I grew up not knowing I had human rights. Believe it or not, I grew up in a small village in Shan State and I thought the only way to live our life was through traditional values.

And this is a very deliberate systemic work of the military, making people think that you don’t have rights, and what they decide and what they do is the only way of making this country safe and better and to protect you, that sort of thing. And the only way that I learnt the real history that we are talking about, and about human rights, was when I came outside Myanmar to educate myself, to study. I’m just one in a million examples.

There’s so many people like us that were living in a very dark knowledge that they don’t have rights. But slowly that was changing, because of the help of the internet in spreading information, but as well as the work of poets, artists, educators and law changemakers. All these people who played important roles in bringing change evaporated suddenly because this coup happened. Like you said, it’s like we’re back to 1963 or something like that again. It’s very painful to watch and go through this again.

Daryl: I think to jump off that, a lot of the pain, of course, also comes in real terms cause many people have died, and many of the poets here are no longer with us. That’s why I made that comment to everyone via email that in some ways the book feels like a mausoleum. I thought this was a good opportunity for Ko Ko to read the other poem, by D Lugalay.

Ko Ko: D Lugalay is a Rakhine poet. He was very active in the civil society and a brilliant poet as well, and you can see it from his poem.

D Lugalay, "Death is not the end"

A bird just died midflight—

its journey half-done

& now in midair

it has just taken

the last breath.

The remaining journey

for the lifeless bird is

the distance between

earth and heaven.

The bird is done with dying,

but not flying.

On earth, however,

death usually means the end.

Then again,

there’s exception

That’s a poem without a full-stop because death is not the end. And I’ll read it in Burmese.

ဒီလူကလေး

သေပြီးလည်း မပြီးတာ

ငှက်ဟာ ပျံရင်းသေသွား တယ်

သူရဲ့ မသေခင် လေးတင် ရှိခဲ့တဲ့

နောက်ဆုံး ခရီးစဉ် ဟာ

ပျံနေရင်း တန်းလန်း ခရီးတဝက်နဲ့ ရပ်ပြီး

လေထဲမှာ သူ အသက်ပျောက်သွားတယ်။

အသက်မရှိ ပဲ ဆက်ရတဲ့ ခရီးက

ကောင်းကင်နဲ့ မြေပြင်ကြား အကွားအဝေးကို သွားရတယ်။

ငှက်ဟာ မလွဲမရှောင်သာ ဆိုသလို

သေဆုံး လို့ ပြီးသည့်တိုင်အောင် ခရီးထွက်လို့ မပြီးဘူး

ကမ္ဘာမြေပြင်ပေါ်မှာ

သေရုံနဲ့ ပြီးသွားတာတွေ ရှိတယ်

သေရုံနဲ့ မပြီးတာလည်း ရှိတယ်။

(translated by ko ko thett)

Daryl: Thank you. That's a very good lead in, because my next question was linked to that point about the dead. In some ways, maybe just to ask broadly, what role does the book play in relation to the dead and what role do the dead play in this book?

Ko Ko: I am one of those–as a poet, I am quite preoccupied and possessed with death. In my book The Burden of Being Burmese, I search “death”, and the most occurring word in that collection is death. D-E-A-T-H. So I’ve been possessed with death, although I have never actually experienced death as such, maybe near death or little death, but not death as such, in my life, the immediacy of death. But I fear death. I am afraid of people dying. I don’t want to see people dying, and so on. So I am preoccupied with death, the idea of death and the afterlife and so on.

When my friends Khet Thi and K Za Win died, even though they died in Burma, and I was in Norwich, UK, I felt the immediacy of their deaths, especially because we were following the news and all these things, and Khet Thi’s wife was interviewed on media and she was weeping and so on. We really felt very much moved by that. So death plays a very important role, but for them, death is not the end; that’s the idea, I think. These are the poets whose deaths are not the end, definitely, and not just Khet Thi and K Za Win, many many others. Not just poets, many many people who died fighting.

Like Dr Thiha Tin Tun, he knew where he was going to, he knew he was going to be shot in the head, so he wrote a will before going out into a protest. And the will is not a will, it’s a suicide note. So death is very much—in this anthology, death is such a huge theme as well. And of course the regime is like death as well to many many people of Burma. They are the living dead, probably, just like they are—we are like zombies, right? I see it as like a post-apocalyptic kind of scenario where the zombies are following the ordinary people.

Daryl: Thank you very much, Ko Ko. Does anyone want to add to that point? Nandar, did you want to add something?

Nandar: Yeah, similar to Ko Ko Thett, about death, I think a lot of the time when we say death we think of actual dying, but I think, just by the junta staging the coup, it’s killing all of us. Not having hope, not being able to do what you are passionate to do, things like that, a lot of things that have been taken away from us is also a way of killing us. I believe that all of us who don't want the coup are dead inside. Because our hope has been taken away. The only reason to keep our hope alive was to collectively go outside and be there for each other and stand up for what we believe (in). That is the only thing that they cannot take away from us. The rest they have taken away from us. So in some ways all of us are dead. Like Ko Ko not being there when his friends are dying, it’s also a way of killing Ko Ko, even though he’s alive and safe in the UK.

So same with me, my family is still in Myanmar. There are so many things I keep worrying about. I wake up in the middle of the night worrying that something might happen to them because this village is burnt, that village is burnt. So I think in some way we are really facing the dead.

Daryl: Yeah, I think that’s definitely true on some level. But I thought, and this maybe is a way for Nandar to read your piece as well, that although there are many dead, even though many things have died, even through the ashes we’re going to see new shoots spring up; that is the title of the anthology. And I think Nandar your work is a lot about new shoots, about making things grow. So maybe you can read from your excerpt and we can go into questions about that as well.

Nandar: Okay, sure. The title is called “A nightmare that you can't wake up from”.

On 1 February I woke up with no cell signal and quickly realised that something terrible had happened. I looked out into the street and saw many people were running and panic-buying.

I needed some confirmation that what I thought happened had happened. I could not check the internet or call anyone to ask. I kept looking outside to get an answer, and saw military trucks playing the national anthem loudly and proudly to declare their success.

I felt devastated, angry, sad, helpless and hopeless, and I froze. Those feelings are complex and hard to process, even today.

From that day, curfews were announced, fears were reinstalled, connections were cut, lives were lost and hope was diminished. That day can be marked as the beginning of living with the familiar fear with which our parents had lived.

As a feminist advocate who has been working in advancing the women’s rights movement for years, it felt like the progress we had made collectively had just evaporated. I felt extremely unmotivated to do any work. It felt pointless and meaningless to be doing anything about gender equity if the dictators were going to rule the country. And, realistically, if we continue doing it inside Myanmar, our lives will be taken away. So, I paused all the work that I was doing—producing the podcast, creating content and providing training.

I started joining the protests every day to show solidarity and because it was the only way to fuel our hope. By showing up to the protests, by standing up for each other, by rejecting the coup, we hope that we will one day get what we deserve—justice and equality.

Being disconnected from the world overnight is such a scary thing—especially when you have been connected for so long.

The experience of living under the coup is like a nightmare that you cannot wake up from. It is like a storm that never stops. It is like an earthquake that destroys everything.

I returned to Yangon from Shan to work on relocating out of Myanmar. On my way back, the highway roads were filled with police and the military intimidating civilians. “Are you joining the civil disobedience movement?” “Are you doing anything illegal?”

What was more startling for me was to witness the sad, quiet, damaged Yangon. Yangon used to be a lively, fun and extremely busy city, especially at night. But now I see very few people walking outside, even in the daytime. There are no loudspeakers, there is no music, no business, no smiling, no crying—just complete darkness with lost lives and unheard voices.

Following the coup, Myanmar has become a country that is hard to recognise as it used to be—peaceful and lively, yet complex, hardworking and beautiful.

We have lost more than a thousand lives and there has been immeasurable suffering, yet we don’t give up. The people who gave their lives for this aren’t simply numbers.

Their lost lives will become scratches on the wall as proof that we fought, and are still fighting, back. The scratches will keep us and our voices alive even if we die.

Yeah, that was it.

Daryl: Thank you for the fantastic reading, Nandar. Actually that leads me quite naturally to the question. Because you mentioned that, even in the excerpt you read, that you’ve been involved in the work of women’s rights for quite some time now. And one observation I had of the anthology, and maybe the events in Burma, was that a lot of the prominent poets are male, but actually, women are increasingly playing a more prominent role in the events that have been happening, and maybe in Burmese society in general, playing a more prominent role. And of course the most prominent of them that comes to mind, of course, would be Aung San Suu Kyi.

Maybe the question to Nandar that I want to pose is, what role women have played in the recent events of 2021, the subsequent response, and how has that changed across the years?

Nandar: Actually I would like to point out that women have always been part of any revolution that Myanmar has. The only thing that is different back then and now is that the media has been more drawn towards telling women's stories. I think I would say again it’s because of the feminist movement globally that is paying attention to women’s contributions nowadays.

Back then as well, women were playing a vital role. And also the understanding of women’s contributions is also changing. Back then, domestic work and childbearing things were things women were supposed to do and they don’t have the option to say no. But nowadays, because of economic independence and financial independence, women can say no to these things, at least some women, you know? Because of that reason, now I think media and people in general are seeing the value that women put in other aspects of life as well.

Of course in terms of numbers, it has increased. For example women who have joined PDF (People’s Defence Force) and stuff like that, would not have happened in the past. But now because women are able to make their own choices, they are able to make a decision on whether or not they want to participate. Back then, they were not allowed to make those decisions. It was the men who made those decisions for women. One example of back then and now is that politically men were more involved and men would kind of... right now, many people run away and hide from the regime. Mostly men were running, women were left behind with their children, and they were the ones building the country as they continue living and they’re the ones who were keeping people alive. Keeping children alive, feeding them, taking them to school, doing those kinds of important jobs.

And now also the participation of women is more diverse. They don’t have to just do one thing, staying home and taking care of the children while the husband is hiding away or running abroad because of the military. Now, they can choose which part of this revolution that they want to play. Whether be it joining the PDF or writing, or... and their potential is also increasingly recognised by the media, and people are deliberately making gender aware decisions.

And because that changed, now the role of women is now also seen as valued by the world and now that’s why it's noticed, but women were always part of revolutions in Myanmar. I want to strongly say that and I feel like that is not really recognised, time to time. People think that it’s just now that women are suddenly becoming part of revolution, that is not true. Women have always been a part of revolution and changes in Myanmar.

Daryl: Thank you for that very illuminating response. I want to pause here to see if Ko Ko or Brian want to pick up on that point? Otherwise we’ll slowly move into a few of the questions that we’ve been getting. But Ko Ko, Brian, anything you want to add to that? If not, maybe I can ask one question, it’s actually my last question, but it resonates with a question that one of our viewers has asked, and it’s simply: What new shoots do you hope will spring from this project? It’s the same question for all of you. What hopes do you have for Burma now? And what hopes do you have for this book?

Brian: If I could just underscore one additional point, just picking up on what Nandar is saying—well, said. Not only have women obviously always been a part of revolutions, they have always suffered the consequences of revolutions, and I think there’s some tremendous reporting being done for example by Emily Fishbein, who’s in the region and who’s invaluable in terms of helping us get in touch with a lot of writers and so on. And she’s been doing some really stellar reporting on the impacts of war for women in particular.

She had a piece in Al Jazeera that discussed the difficulties of childbirth, for example, and having to flee into the jungles, having to essentially give birth during this conflict and the tremendous difficulties and dangers that women have to face in order to endure that. So that’s the other sort of flipside of this as well, and it’s because of the courageous reporting by people like Emily and others obviously, that we’re becoming aware of these conditions and things that women have to endure, essentially because of men with guns who overthrew the government and are trying to impose their will through violence.

Daryl: Thanks for that.

Ko Ko: If I may add to that point. One of the explanations of women empowerment, for instance in countries like Finland, which is considered to be one of the advanced countries when it comes to women empowerment, is that so many young men died during the Second World War. They died fighting against Stalinist Russia in the Second World War. In the domestic area, women remained and they continued to build the country. So that’s one hope that we could have, you know, in this scenario where many young men—for women in this dark time, but I could see that women would be more empowered through their struggle. That’s one of the hopes, I would say.

Daryl: That’s a very rich discussion there about the role of women, and I think it adds a lot of nuance to the picture that has been forming. Maybe let’s go to the questions, since we have about 10 minutes more.

What are the challenges and risks of making the liberal translation of this anthology?

I'm not sure if Ko Ko and Brian will agree that this was a liberal translation. But maybe I can just ask you to comment on the aspect of translation and how challenging it was or what difficulties you faced or issues you had to sort out, in the manner of translation.

Ko Ko: We put out a call for submissions. So those poems and essays that were submitted in Burmese, of course, the writers and essayists, they knew that I would translate them. It’s not liberal translation, but I try to be as loyal as possible. And when possible I consulted with the writers, like “Spring” by Nga Ba. I know the poet, so I show them my translation. And that’s how it worked. Not quite liberal, I would say.

And then there’s poets like Khet Thi and K Za Win. I’ve been translating them before 2021, so many of the translations they have read, and they knew. So that’s how it worked. And we should note that there are several other essays and poems written in English, like Nandar who wrote in English. So there are at least five to ten poems and essays written in English, so not all of them are translations.

Daryl: Yep, thank you very much Ko Ko. Brian, do you have anything to add for translation, or that’s pretty much…?

Brian: No, I mean Ko Ko was obviously the point person with the translation and I believe his wife did a number of translations as well. But there were the obvious logistical issues too with getting in touch with some of the writers under the circumstances, so that sort of complicated things to a certain extent.

Daryl: I see. Okay. Maybe I can ask a related question that’s also come up in the comments: How did you come to have the book entirely in English, and what was the thinking behind that decision? And I assume the question is why not in Burmese as well?

Ko Ko: That is the publisher’s decision actually. We wanted to make it bilingual, but then to make it bilingual it wouldn't have been possible for us to get the book out within a year of the coup. It is a nightmare, I know because I have done a bilingual anthology of Burmese poetry, and it’s really difficult, especially with a printer and publisher that’s not familiar with the Burmese text. So a lot of extra work.

But then now we are thinking of a Burmese-only anthology. We would have to then request those who wrote in English to re-translate their essays and poems into Burmese, like Nandar.

Daryl: Okay, so I hear that it’s mostly a logistical or publishing arrangement.

Ko Ko: Yes, so as a tokenistic measure we put the handwriting of some of the writers, like Khet Thi and Min Lu, just to honour the Burmese script and their original handwriting.

Daryl: Thank you for that. I guess a related question which has come up as well, and I guess that points to the following question (because we have poems and non-fiction): why there was no fiction in the anthology. Was this a conscious decision and maybe you can give us a bit more insight as to why there’s no fiction and no works of prose in this anthology.

Ko Ko: We decided on poems and essays, but the initial thinking was that we wanted to document the protest movement, writings, first-hand accounts of the protests, so it has to be out of the protests. That was the beginning of the anthology. Poems and first hand accounts out of the protests, that was how it was conceived, and then we continued that way. No fiction.

But then some of the stories are stranger than fiction like “My Story” by Ningja Khon, who had to flee for her life.

Daryl: Okay, so meaning that the starting of this anthology was rooted in personal experience of the protests.

Ko Ko: Yes, exactly.

Daryl: There’s a question for the publisher, which is the next top-voted question, maybe Kah Gay can try and answer it when he comes on, and maybe Kah Gay can prepare for this. And the question is about what challenges did the publisher face coordinating with other publishers and making the ebook available for free?

There’s maybe one other question; this one is quite relevant, because in some ways this book is a call of attention to the events in Burma. And the question asked: How can the rest of the world best support the creative minds from Burma? How can the rest of the world support the creative minds, artists, writers from Burma?

Brian: I mean, in the first instance, by supporting the book, by buying the book, by distributing the book, by sharing the book, by posting about the book. By reading these poems, getting to know these writers, getting to know their works, talking about it, I think that’s the first immediate step. And I think this circles back to the question of why we did it in English. We wanted to have a much wider audience. We wanted to really draw attention to what’s happening within the country amongst those outside of the country.

Because the people within Myanmar know what’s happening. They experience this on a daily basis. Those outside the country obviously have a very small window into it through things like the media, but it’s important to have the voices of the people within Myanmar amplified and to have those voices spread.

So supporting the book I think would be one thing, and I think Ko Ko and Nandar would be in a much better position to talk about the various cultural organisations or initiatives within Myanmar that people could support.

Nandar: Thanks. I feel that one of the greatest disservice that we could do to a situation or to a problem is by not trying to understand it and jumping into conclusions and making assumptions. So I think the greatest support would be the first step to understanding the situation.

I see a lot of people on Twitter, especially, people who are not from Burma, making a lot of assumptions and judgement and conclusions, and misleading the conversation to point to other things that are not necessarily important to discuss at this point, you know? And I think that can be a great disservice.

So I think the first thing, if people want to support, is first to know and understand what the problem is, and understanding how exactly you can support without supporting from a colonial mindset, thinking that you are superior in approaching the problem.

I think the best way to support someone is through humanity, having a human mind to the other person. I don’t know, those are the two basic things I think, no matter how you’re supporting, whether you are supporting financially or by giving your service or any other aspect. I think that’s the two basic things that one needs to know before actually helping. That you are helping the other person with dignity, you know, not like you pity them, “I feel sorry for you” sort of way, and the other is understanding the situation. Or like Brian said, understanding these writers who are going through these things. So this gives the situation a human story. It makes people better understand it through people’s lens and through people’s life. So I would say those two things. Ko Ko, do you want to add?

Ko Ko: I think it's really important to let the protagonists or the people speak. That’s what we try to achieve with this book, albeit a translation, right? We really wanted those who were out of the protests to speak for themselves, and they were able to do that. It's not us.

And in the beginning of the project we decided against ownership as well, we don't own this, not financially, nothing. We cannot do it for profit. It would be morally wrong to claim ownership for this book. So we were very grateful to Ethos as well, to make it a pro bono project and sell the book just to cover the costs.

Daryl: Great, yeah, I think that’s a good note to end on and to invite Kah Gay to come out, because I think what is really imperative now is for people to read the book and to hear the voices for yourselves. So please do that, it is I believe a free e-book on Ethos, and Kah Gay can tell us a bit more about the book.

Kah Gay: As I'm responding to the questions relevant to the publishing house, I would first like to thank the four of you, because you have given us a very honest, intelligent and very deeply moving conversation.

I find it very deeply moving because there are so many points of connection that you’ve made in your discussion. You have reduced the distance between earth and heaven, and also between life and death. The dead speak to us through the writing. And actually their suffering I feel makes us more alive to the freedoms that must be protected. So thank you so much for bringing all this out.

I think the answer to one of the questions about translation and whether we should have done it bilingual—thank you Ko Ko, for already sharing a bit about that. It also ties in to the democratic vision that I believe is at the heart of this project.

This project must not stay in Myanmar. It must go out to the world. Ethos Books is hopeless at the Myanmar language, I’m afraid, but we believe that the English edition will be important. And that’s why our ally publishers, Gaudy Boy and Balestier Press—by working with them we can now bring it to the US with Gaudy Boy and the UK with Balestier Press.

Those are printed books that have power because when you hold something, it is concrete. It’s like the pots and pans that people bang. However humble the object, I think those are the things that matter. It’s a very powerful, very stirring vision and sound that I totally feel very proud of to be part of, and my team will say that. And Daryl, thank you so much, you are now part of this team.

I think the second question is really about the logistical problems that come about working with different publishers. These are challenges that we want to overcome because it’s like a democratic raft. The powers that be are really mammoth and monolithic. We need to band up and raft together, just like the ally publishers. With just two more, we speak so much louder.

So I think this collection… I am so happy whenever we hear from Ko Ko and Brian, we know that their hearts and spirits are in the right place. They value the voices. It's never about who owns it, and that’s why right from the beginning we knew we had to make the e-book available for free, so go ahead to download it from Ethos’ webstore.

If you want to support the publishers who have committed to this vision, you can buy from the US website (from) Gaudy Boy. We want to be environmental, so order from the place nearest to you. Order from the UK press, Balestier Press, they have a production in the UK, and if you're in Singapore and the region you can order from our webstore.

So maybe I would also like to end on a very positive note about how your voice and your action can help to spread the word and the voices of our poets, our writers.

The Projector which is an independent cinema in Singapore, they have collaborated with us to make available a documentary titled Padauk: Myanmar Spring. It documents the lives of the protestors and human rights activists in Myanmar after the military coup.

You can look at their stirring documentary on the Projector’s Video-on-Demand platform, and I think I would like to end my closing note by asking that we continue to remember the voices and the poems and the writings, together with our wonderful editors, contributor and moderator. That’s all I have to say for tonight; Daryl, do you want to close the session?

Daryl: Nope, I think all that remains is to thank everyone who’s joined us online and spent this hour with us. I hope you found it as engaging and interesting as I have, because I’ve certainly learnt a lot more through this session even as the moderator. Please download the book, please buy the book, and amplify these voices in whatever way you find best fitting. Thank you very much and have a good evening, morning, afternoon, wherever you are.

About the Speakers:

Ko Ko Thett is a Burma-born poet, literary translator, and poetry editor for Mekong Review. He started writing poems for samizdat pamphlets at the Yangon Institute of Technology in the ’90s. After a brush with the authorities in the 1996 student protest, and a brief detention, he left Burma in 1997 and has led an itinerant life ever since. Thett has published and edited several collections of poetry and translations in both Burmese and English. His poems are widely translated and anthologised. His translation work has been recognised with an English PEN award. Thett’s most recent poetry collection is Bamboophobia (Zephyr Press, 2022). He lives in Norwich, UK.

Brian Haman is a researcher and lecturer in the department of English and American Studies at the University of Vienna. He completed his PhD in literature at the University of Warwick (UK) and has studied or held research appointments in Europe, China, and the US. A book, art, and music critic, he writes widely on contemporary culture from Asia, and, since 2017, has been an editor of The Shanghai Literary Review. His forthcoming books include an anthology of contemporary Chinese-language poetry in translation as well as an edition of the unpublished works of exiled Austrian Jewish writer Mark Siegelberg.

Nandar is a feminist advocate, a storyteller, and a podcaster from Shan State, Myanmar. She is the founder and Executive Director at Purple Feminists Group and hosts at G-Taw Zagar Wyne and Feminist Talks. She also translated and published world-renown author Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie's essay books Why We Should All Be Feminists and Dear Ijeawele or A Feminist Manifesto in (15) Suggestions into the Burmese language. Nandar co-organized and co-directed The Vagina Monologues in Myanmar for three consecutive years since early 2017 and was listed as one of the 100 inspiring and influential women from around the world for 2020.

About the Moderator:

Daryl Lim Wei Jie is a poet, editor, translator and literary critic from Singapore. His first book of poetry is A Book of Changes (2016). He is the co-editor of Food Republic: A Singapore Literary Banquet (2020), the first definitive anthology of literary food writing from Singapore. His latest collection of poetry is Anything but Human (2021). His poems won him the Golden Point Award in English Poetry in 2015, awarded by the National Arts Council, Singapore.