"Learning and growing from my experiences—that’s what gives me a fulfilling life." | Delicious Hunger Book Launch

The book launch of Delicious Hunger took place on 26 April 2025. You can access the full transcript of the programme on this page. This translation was offered in real-time and has been minimally edited for grammar, spelling and clarity.

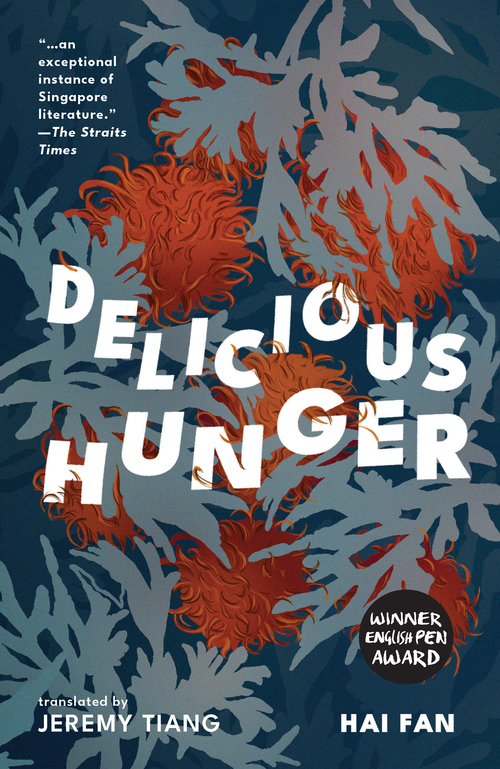

About Delicious Hunger

Winner of the PEN Translates award

From 1976 to 1989, Hai Fan was part of the guerrilla forces of the Malayan Communist Party. These short stories are inspired by his experiences during his thirteen years in the rainforest.

Struggling through an arduous trek, two comrades pine for each other but don't know how to declare their love; a woman who has annoyed all her comrades finally wins their approval when she finds a mythical mousedeer; improvising around the lack of ingredients, a perpetually hungry guerrilla makes delicious cakes from cassava and elephant fat. The rainforest may be a dangerous place where death awaits, but so do love, desire and hope.

Delicious Hunger is a book about the moments in and between warfare, when hunger is so palpable it can be tasted, and the natural world becomes an extension of the body. Deftly translated by Jeremy Tiang, Hai Fan's stories are about a group of people who chose to fight for a better world and, in the process, built their own.

You can find the speaker bios at the bottom of this page. Enjoy the conversation!

Photo of the speakers. Left to right: Dr Tan Chee Lay (moderator) and Hai Fan (author).

Photo of the speakers. Left to right: Dr Tan Chee Lay (moderator) and Hai Fan (author).

Introduction

Chee Lay: Hai Fan, I’m very happy to be speaking with you today. Do you know what I thought when I first encountered your writing? I felt like I had found a pearl in a shell. I didn’t realize that such vivid writing on MCP history existed in Singapore.

(To the audience) We had originally wanted to use AI to translate, but we found that human translation was faster.

We hadn’t known, for a long time, that Hai Fan had been among us. We hadn’t known that there was someone like him in Singapore, until he decided to open up to the community here, to allow others to know him.

Hai Fan: Good afternoon everyone, I’m very happy to meet you here today. It’s not my first time participating in cultural events, but an event like this is special. We all know that Singapore is a multireligious, multiracial and multilingual society. We live together, but interactions across languages are quite rare. It’s almost as if we exist in parallel, doing our own thing. Today, two parallel lines are meeting.

Because of Delicious Hunger, our friends from both the Mandarin- and English-speaking communities are here today. I’m very thankful to Jeremy Tiang, who translated this book, Chee Lay, who’s moderating, and everyone who’s here today.

I’m full of anticipation for today’s event. Thank you everyone.

Chee Lay: when we listen to Hai Fan speak, don’t you feel like he sounds a little different from everyone else? He sounds very precise and formal. It feels almost as if he was trained in the military. This is what Li Zi Shu writes in the afterword of the book. His dress, posture and way of speech are unique. These characteristics, which also apply to his writing, have never changed.

In 1976, when I was just 3, Hai Fan entered the rainforest. For thirteen years, he was in the rainforest, separated from society. While he engaged in guerilla warfare, he also wrote. Only later was his writing edited and collected into a book.

Moderated Conversation with Hai Fan & Tan Chee Lay

Chee Lay: Let’s begin with your personal writing journey. How did you start writing, and what topics did you first write about?

Hai Fan: My experiences with writing and the MCP… Let’s start with my pen name “Hai Fan”. The use of “Hai Fan” today is different from that in the past. When I was in the rainforest, I use a different pen name. I don’t remember the pen name—it had been chosen for me. It could have been a woman’s name if I had written from a woman’s perspective. I first used “Hai Fan” to start writing songs. I wrote over thirty songs under the name “Hai Fan”. That is the past life of “Hai Fan”.

Chee Lay: Do you still sing those songs?

Hai Fan: Not really. I wrote my last song in 1988. I started using “Hai Fan” again in 2014. That was a transitional period for “Hai Fan”. I published a collection of writing from my time in the rainforest. When I started writing this book, I was not planning to use “Hai Fan”. I was using the name “Xin Yu”. “Xin Yu” had gained some fame and popularity. I was initially reluctant to use “Hai Fan”, or to associate it with “Xin Yu”. I denied association.

In 2015, I started using “Hai Fan” consistently again. At the start, my writing was published in Sin Chew. It was also published in Taiwanese papers, but at that point, this type of content was less accepted in Singapore. From May 2015, I started writing under “Hai Fan” and have continued till today. Delicious Hunger was published in 2016, as the first book written by Hai Fan. Today, it’s been translated into English.

Chee Lay: This was published in 2016, but in 2015-2016 you wrote a lot. Those two years were highly productive. Is it related to your return to “Hai Fan?” That’s my hypothesis. (to the audience) None of these are in our pre-decided list of questions.

Hai Fan: Yes indeed. This is a good question. When I returned, I wanted to settle down. I was 40. You can imagine, as a middle-aged man in singapore, that’s difficult. Neither of my parents was educated, so I had to rely on myself to settle down, which I spent ten years doing. But I had a lot to say. But at the time, because I couldn’t, I used “Xin Yu” to write some other stuff [stuff unrelated to Hai Fan’s MCP experiences]. It was only in 2015 when I was persuaded by Li Zi Shu that I decided to revisit my time in the rainforest. It was like a creative eruption. I didn’t know how to put it together, so my first story took half a year to write. Thereafter, it took me about a month to write each story.

This story collection spans thirty-five years. I have a habit of noting down the date of completion for each story. Because we use the laptop to write, we also know when we start and finish each story. For me, a 6,000-7,000 story took about half a month. What surprised me was that I wrote a new story every month, so I was able to publish a book in 2016. What this shows is that I had many things suppressed within me—when I finally decided to write it all out, it all tumbled out.

Writing is complicated—it’s a learning journey.

Chee Lay: (to the audience) Li Zi Shu is the author of the afterword of Delicious Hunger. She’s also a prominent author in Malaysia. One of her novels is being adapted into a TV series in China.

Hai Fan: Li Zi Shu encouraged me to continue writing. She met me when I was using “Xin Yu”. It was later when she herself wanted to write about the MCP that she approached me. At the time, I was reluctant to write about my experiences, but she encouraged me to, so we had tea. Then, she learned that I was Hai Fan, and then she finished reading my book in two days.

After that, she sent me an email asking, “How can you stop writing? You have to keep writing!”

But at the time, I was still very hesitant. I had settled down, and I feared that revisiting my experiences would create uncertainty. I asked my friends, should I write about my experiences? They discouraged me. But finally, I felt I had too much to say.

Stepping into the new millennium meant that conversations about the MCP were less repressed, so I felt less suppressed myself, and I began writing.

Chee Lay: I’m very moved by Li Zi Shu’s words: she says that you might be the only person with the tools to uncover the experiences of the MCP. By “tools”, what she means here is your pen.

Hai Fan: She was encouraging me, haha. When I started writing, it was because I had much to say from the bottom of my heart, but I felt quite lost at first, because I didn’t know how to organize my thoughts and experiences. I had left the rainforest for 20-30 years, so there was already a distance. How could I write about these experiences? It took a lot of thought, and it’s a learning experience.

At the time, I thought—since we (the MCP) had endured for 40+ years—it’s not like going to a field camp for a week. It’s an entire society that lived in the rainforest for 40 years, though at first, this society had not been fully built. So first, I learned that I had to write about the MCP as a society, as a state of existence.

Second, I felt I was just a normal infantry soldier. I didn’t know what I was going to do the next day. I would only find out at night what my tasks would be the next day. I had little control, as I was purely an allocated resource. As such, I thought from the perspective of the most “lowly” and basic man, so I also wrote from the perspective of the ordinary human. Many felt I was writing in view of the ordinary human condition.

When people are hungry, there are two levels. One is semi-hunger, the other is full-hunger. These are different. You don’t know what the feeling of full-hunger is until you have actually experienced it—months with little food. Under those conditions, what happens to your thoughts and emotions? It’s very different from what happens in normal society / existence.

In these years, I’ve realized that I should write more about the experiences I had in the rainforest. The rainforest is foreign and appealing to many ordinary people—they are curious about what it’s like living in the rainforest for months or years. Next, Jeremy Tiang will be translating “the rear view of the rainforest”, but I told him to wait.

Chee Lay: Many of us have gone through the army and complained while going through that. You are able to translate that frustration into your strength in writing. Let’s now turn to this book. Why did you choose to title it Delicious Hunger? Did you consider other titles? Did you encounter any challenges in the process of turning these experiences into short stories?

Hai Fan: This title was not my original choice. It was the title of one of my stories. I had chosen “Wild Mangoes” as the name of the book. My editor encouraged me to use “Delicious Hunger”. Now I agree with him. “Wild Mangoes” is not as unique, and not as unique to the rainforest. “Delicious Hunger” creates a sense of mystique by itself, given the paradox. Many remember the name of the book without necessarily remembering my name.

Why “Delicious Hunger”? There’s a character with the nickname “Delicious”. He said everything was “delicious”, so that became his nickname. He’s now living in Malaysia.

Secondly, in hunger, everything is delicious. Without being truly hungry, you are unable to fully appreciate the deliciousness of food. Without having eaten rice for years, we were mostly eating tapioca and starchy food. After that, we came to fully appreciate how delicious rice is.

Thirdly, I think that humans need to undergo challenges. Only then will you grow and feel like there’s flavour in life. That’s why I like this title so much now.

But I realized that when you translate “Delicious Hunger” (back to Mandarin, using a translating software), it rarely turns out as “可口的饥饿” (the title in Mandarin, pronounced as “ke kou de ji e”).

How do you think we should translate it?

Chee Lay: Delicious is “kekou”, hunger is “ji e”.

Hai Fan: Yes, but when you put it in deepseek, it doesn’t turn out as such

Chee Lay: Hunger can be physical, psychological, or spiritual. What is the relationship among these different forms of hunger? Are they complementary, does one increase while another abates, or something else?

Hai Fan: Chee Lay’s question is quite academic. Perhaps I can approach it from a more mundane level. We were hungry because we were isolated in the rainforest (about 3-4 days’ journey from the nearest village). We had to live in the rainforest and live for our ideals in isolation for the long-term. It’s not a short-term stint.

There’s a story called “Buried Rations” in the collection. When we buy rice from outside, we don’t eat it first. We bury it. Instead, we eat what was buried 10 years before. As I have said, the MCP had been in the rainforest for 40 years, so we were eating what others had buried before us.

There’s a map for these buried rations that we could consult. Everything we ate was at least 10 years old. You probably have not eaten rice a decade old.

Why did we do this? To continue the struggle. This is to ensure that we will always have buried rations. When we left the rainforest, someone asked, how much more buried rations do we have? Can you all guess?

Chee Lay: 10 years?

Hai Fan: yes. We kept track of everything, and there was still 10 years’ worth. Of course, it was not enough for everyone to eat till they were full. We had to mix it with tapioca.

Chee Lay: let’s continue. We’ll do an activity on ingenious contraptions later, so let’s talk about this. How did the guerillas obtain, transport and store food?

Hai Fan: good question. If I gave you rice and ask you to bury it, how do you ensure it’s edible in 10 years? It’s a very technical question. How did we bury it?

We buy rice from outside. We make a metal container. Put in salt, sugar, rice. But think about this—it’s so humid, isn’t it?

To solve this, our “old comrades” coated the outside with resin. This is the resin that a tree creates when it’s injured. We used the resin of the meranti tree, then added kerosene, then boiled it. After you boil it, it looks black, like tar. We would then coat the metal container with this paste, then attach a plastic tarp over it, making sure that there are no air bubbles.

Only then would we put rice in it, then seal it with the same paste. Then, we choose a place to bury it. The rice will keep for 10-20 years. This paste separates the rice from the humidity of the environment.

Chee Lay: (to the audience) for those of us who have books, we can look at the glossary.

Hai Fan: I understand that it’s hard for people outside the rainforest to imagine these contraptions, so I included a glossary. These (referring to the sketches of containers in the glossary) are two different sizes—the big one can contain more than 100 pounds of rice.

At the time, I thought that this paste, which we call “da ma”, was a name that only we MCP guerillas used. Last year, I learned that I was wrong. Many indigenous peoples, the Orang Asli, used this paste. They used it for lighting. They would put this paste in a bamboo pole, then light one end—it would then act as a torch. We used such torches when we had meetings at night.

Chee Lay: the wisdom of the indigenous peoples. After so many years, how does it feel to revisit your time in the rainforest? Is this chapter of your life one you reminisce, bury, or one for which you are grateful for the writing material ? After thirteen years of hardship, how do you view life and death, extreme hardship, and especially the hunger that permeated the whole experience?

Hai Fan: This is a complex question. At different phases, I view it differently. Sometimes, I want to bury the past. Once I started writing, I felt differently. Friends told me it was worth it for the amount of writing material I generated, but that was not my purpose for becoming a MCP guerilla. That is impossible. I am a survivor. There are others of my age who were unable to survive. I had no idea that I could. As an ordinary soldier, I had little control of my fate.

I would see my comrades return with a leg gone, and others not return at all. When we send our comrades out each time, it’s a big deal because you have no idea if you will see them again. The question at the back of my head was—when will it be my turn?

What do these experiences mean for me? I’m 70+ now—¾ of my life is probably over. Life can be long or short, but few live to 100+. Things will pass, everything is empty. IS life meaningless? Some say life is about finding meaning in the meaningless. Regardless of how long you live, it is a process. From a meta view, there’s not much difference between living till 30 or 80. I don’t know if this is the right way to think about it, but I think it’s about how you face adversity, and how you find meaning and grow from the process. In a difficult life, finding meaning and learning are the most important. That’s what I focus on today.

Learning and growing from my experiences—that’s what gives me a fulfilling life.

Chee Lay: You continue to write productively today. This translated book is now shortlisted for the Baifang Schell translation prize. What does writing mean for you today?

Hai Fan: I think of it as a sharing. I hope that my unique past experiences can be presented as a reference for readers—that there was such a type of existence.

Chee Lay: Is there a sense of purpose from sharing the experiences of your past comrades?

Hai Fan: Not really. I think many people like reading about experiences that are different from their own, but are fundamentally human. I don’t have too many thoughts about purpose.

Chee Lay: Looking ahead, how do you imagine your writing will look? Many people want to continue reading your work. How will you better your own writing?

Hai Fan: We don’t need to compete against others—the most important is to improve yourself. I have a different pen name and writing identity under “Xinyu”. You can find my writing in other publications. This writing comes more from my experiences outside of the rainforest—before (from my childhood) and after (my return to society). I write about what moves me in my daily life, away from the rainforest experiences.

Separately, I’ll continue to write about my time in the rainforest. A fellow writer pulled me into a conversation on nature writing last year because I had firsthand experiences, so I thought, since I do have that experience, why not write a nature-themed collection?

On Sin Chew Daily, I now have a column on nature called “In the Wild”.

Chee Lay: That’s a very apt title. I’m looking forward to your nature writing—please invite me into the rainforest. Let’s get to know the Singapore wild better. Let’s now give the time to the audience. Any questions?

Q: Thanks for your sharing. I want to ask a question about history. It’s simple but also complicated. I wanted to ask why you decided to leave everything behind in 1976 to go into the rainforest to be part of the MCP. What were the political, economic and personal circumstances that led to this decision? I’m asking because 1976 is also when the cultural revolution in China ended.

Hai Fan: This is a question I often get. If we look back, Singapore became an Asian tiger in the 80s. Many asked why I decided to leave then, to endure hunger and war, to endure things that most people today don’t have to live through.

But to answer this question we have to return to the circumstances of the time. In the 70s, Singapore’s industries underwent a structural change for the third time, so we developed rapidly. Because of this, a lot of capital came into singapore. At the time, class conflict was not like it is today. In Singapore, there was still a lot of class oppression, unlike today.

At the time, the leftist movement was still going strong. All over the world, including in Asia and Europe. It was like a “high tide” moment for socialism. I was heavily influenced by such socialist ideas. My family had a hard time as we were poorer, and so were those around me. That made me think, what would be a better society? We lived in an attap house and all that. So at the time I thought, how can everyone’s lives become better?

At the time, China was going through the cultural revolution. In Singapore, you couldn’t get the People’s Paper (from China), but you could get it in Malaysia. I got a copy from Malaysia and I thought, ah, that’s what we should aspire to! That’s how, as a young person, I started developing leftist tendencies.

Around that time, I took the train to Malaysia in the night because I was being pursued. On September 9, the day I went to Malaysia, Chairman Mao died. Then the cultural revolution ended. So it’s ironic. At this turning point, while china was going into a new era, i was stepping into the old one.

Q: In 1975, the Viet Cong… (missed question) Did you listen to the MCP radio?

Hai Fan: On the domino theory—at the time, many were “falling” to communism. It felt like there was a wave of reform in the region. But yes, I listened to the MCP radio.

Q: I am a reader from singapore. I want to share a little bit about my understanding of the rainforest after reading Delicious Hunger. We tend to think of the rainforest as a scary place. Our ancestors who came to Singapore will tell you that the rainforest is a “jungle” full of dangers, spiritual and physical. They’ll say that if you die in the rainforest, all that’s left will be your skeleton. Hai Fan’s writing changed my understanding of the rainforest. The rainforest is rich with stories and life. A group of courageous people were able to live in the rainforest—they were an entire society that was disciplined, like an army of ants that buries rations. Hai Fan’s short story collection is very vivid—worth many rereadings.

Now I have a question. How big was your campground? How many football fields is it equivalent to? Were there really tunnels? Did you have a central kitchen in your campground? You talk about eating a lot, and about cooking in the kitchen. I’m curious about many things-–did you get maggi mee, I mean, you even got mooncakes… did they teach you what was edible and not?

Finally, I have a question—of the 22 soldiers who returned to Singapore, did they have mental health issues? Did they have gastrointestinal issues?

Which of your books would you recommend readers begin with?

Hai Fan: this is a very attentive reader, but I’m afraid I’m unable to answer each of these. We lived in the mountains, not on flat ground. Campgrounds were on hills, so it’s difficult to estimate how many football fields they covered. I lived in 15-16 campgrounds—they were very fluid. Not all of them have tunnels, but most had longkangs. These we used to hide from enemy planes and bombings. They stretched across the campgrounds and were difficult to set up—took months. After setting them up, you might have to move campgrounds not long after.

There were central kitchens. Hundreds of people to feed. I’ve worked as a cook before, woke up at 4am to prepare tapioca rice for the day and worked in 4-day shifts. Interestingly, preparing food for 100-200 people required a lot of cooking—so smoke became a problem. So you had to cook before sunrise. With too much smoke, the enemy will find you very easily. We had to find solutions for starting fires and releasing smoke. We found a way to disperse the smoke gradually, along a slope, then channelled it into a tunnel before slowly releasing from the ground.

In 1989, there were 22 Singaporean guerillas. Around 6-7 came back after the peace agreement. 4-5 couldn’t endure and became AWOL while in Thailand before eventually making it back to Singapore. Some were captured in Malaysia before eventually being released back home as well. Now, there are probably 11-12 ex-guerillas. Have not heard of any of them suffering serious PTSD.

The stories and myths that created fear of the jungle—these represent fears of the unknown, similar to our fear of death. We are naturally afraid of death because we don’t know what will happen.

I was similarly fearful of writing under the name “Haifan”, because I didn’t know what wouldhappen.

Q: I would like to know more about the differences between semi- and full-hunger, and how people react and change under these conditions.

Hai Fan: Semi-hunger is a state characterised by a lack of nutrients. I lived in this state for most of my time in the experience. There was a lack of protein from having a tapioca heavy diet. Sometimes we hunted for wild boar, but this was rare. We wanted coffee not for the caffeine, but for the sugar inside, which gave us energy. This is semi-hunger. We were carrying 50-60kgs—we were expending a lot of energy, so we needed sugar from the coffee. We were constantly low on body fuel.

We ate unripe bananas in our hunger. They were hard, so we squeezed them until they were soft and edible. In the semi-hunger mode, we sought for anything that gave us energy.

What is full hunger? Besides the clothing and equipment on us (10kg+), we needed to carry 1 month+ of rations. In the mountains, after a month of semi-hunger, we’ll be out of food and go into full-hunger mode. There is no food. While walking, we will have to look out for edible fern rhizomes in the rainforest. You can find these in parks in Singapore.

In full hunger, there are a few things that happen. 1) We liked to talk about food. This was an unsuppressable compulsion—we’d start talking about char kway teow. 2) everything seemed edible. Charlie Chaplin has a movie where he stared at his fat companion until he saw a chicken. You’d start wondering if things were edible. There are tragedies where guerillas died because they ate fungi and berries that they did not recognize. The death was immediate.

I had two close shaves. Once, when we were walking in the mountains, we came across a deserted kampong. I picked some berries off a tree at the kampong—started thinking to myself and wondering if I could eat them. Finally I couldn’t resist. Peeled the fruit and ate it. Interesting note—99% of sour fruits are edible. Sweet or bitter fruits are dangerous. When I bit into the fruit I picked, it was sweet. So I ate one more. Then I realized it was sweet. What do I do? Was it poisonous?

I told my buddy that I ate the wild berries. But I survived. I had convinced myself internally that it was edible, since the berries were at an old kampong—no one would grow toxic berries.

Another time, while recee-ing, I saw a fruit slightly bigger than a mango on the ground. It emitted a faint milky scent. Was it breadfruit? My buddy and I convinced ourselves that it was. Also we saw that there were bugs on the fruit—we convinced ourselves that if it was fine for the bugs, it must be fine for us. Luckily, the fruit wasn’t poisonous. We didn’t dare to tell others that we had eaten the fruit.

These were the irrational choices that we made due to being in the full hunger state.

Chee Lay: Due to time constraints, we will do a shorter version of the activity that we had planned.

Hai Fan’s prompt for the activity:

How do you solve the problem of sourcing water in the rainforest?

Draw a contraption that allows you to collect water in the rainforest.

Chee Lay: Everyone, our event is ending soon. Let’s settle down before the book signing. I’d love to do a concluding remark today.

I have rarely been to an event where the audience is so excited. Thank you, Hai Fan, for immersing us in the time and place of the rainforest, for giving us a glimpse.

If you’re interested, do pick up a copy. Capital 958 has also recorded some interviews with Hai Fan—you can also learn more about his experiences in the rainforest on Capital 958.

Let’s give a round of applause. Thank you everyone. Let’s keep the chairs, then Hai Fan will be able to do a book signing.