"Unless you speak up and make it public, people won’t think about it": Book Launch of Constance Singam's Where I Was

Livestream of Where I Was

The book launch of Where I Was was livestreamed on Facebook on 20 March 2022. You can watch the livestream above and access the full transcript of the programme on this page. Portions of the transcript have been edited for clarity.

About Where I Was

Where I Was: A Memoir About Forgetting and Remembering is a rich, entertaining and compelling account of the life of an extraordinary woman. In a land of many cultures, many races, many religions; in a state where politics and public policies impinge, sometimes callously, on the daily lives of its denizens, Constance Singam is an individual marginalised many times over by her status as a woman, an Indian, a widow and a civil society activist.

Through humorous and moving accounts, Constance captures in words the images of the people, places and events that are the source of her most powerful memories. These images are connected to key turning points in her personal journey, set against or within the context of important historical events. In this reissue of her 2013 memoir, Constance reflects on current advocacy movements and on the events that led to the AWARE saga that would shape the rest of her life.

You can find the speaker bios at the bottom of this page. Enjoy the conversation!

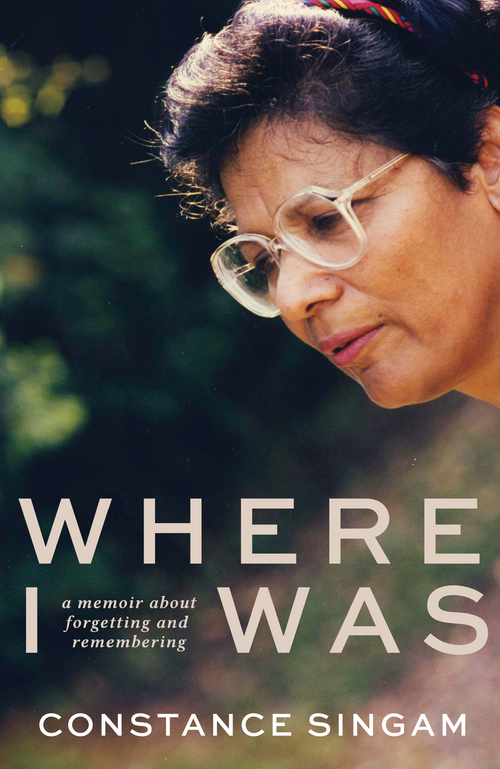

Photo of launch. Credit: Dahlia Osman. Left: Constance Singam. Right: Balli Kaur Jaswal

Constance: Thank you all very much. I just want to say a few words to really thank you for being here, and thank you for the last two weeks of controversy, for supporting Ethos particularly, and being angry. I think it’s important to be angry. When one of the newspapers rang me up and asked me “what was your reaction?”, I said “there we go again.”

I’d been thinking about what I said. I was normalising the behaviour, and we should not normalise this. Every now and then, we have to get angry. Anger is very energising. One of the problems that we are confronted with is culture. People who made the decision to censor the book are people who have grown up in this culture, and how do we break that and change that culture? It’s by being angry.

Everytime something like this happens, we have to protest, we have to be angry. So really, the person I have to thank particularly for getting us upset and angry, is Balli. Balli was the first one to raise that. Before that I thought “Well, this is what life is like in Singapore.” I’m glad that she did, and I’m glad that we got angry, and I would like to thank Ethos team too, for the way they have handled this matter. It was wonderful to see that every generation of people have to fight the system to change it. And by fight I don’t mean being aggressive.

I remember there was something last week Maliki Osman said you have to be respectfully advocating, and I’m not quite sure what that means. I hope he doesn't mean we have to be supplicants, because we are citizens and we want to contribute to the kind of society that we want. And that’s our responsibility in civil society. So thank you for being here and thank you for being in the community that is going to make a difference to the value system and the system that can be oppressive to our creative lives. Thank you all very much.

Balli: Thank you so much Constance, and thank you all for being here. I was going to begin by introducing Connie, but obviously she needs no introduction. Connie has given us some wonderful context to begin this conversation about her incredible memoir, Where I Was. And I wanted to start with the framing of the memoir, because I think that’s really important. The memoir begins and ends with the AWARE takeover in 2009 and I wanted to ask you just to begin with, why frame the memoir with these events? We know, obviously, that they were very significant to you, but given all the memories and narrative arcs in this memoir, where does that reside in your memories?

Constance: When I first wrote the book ten years ago, it was as a result of the Saga. But I didn’t begin with the Saga, I built it towards the Saga. Because I was asking myself the question, how did I get entangled in this controversy, the most important exercise in democracy that has happened in Singapore since independence? How could I get entangled, how did I find myself in the middle of it?

Balli: And you kind of come full circle with the memoir because you end with the AWARE Saga as well. Because I think it really did kind of round out that narrative about your identity, as a woman, as a Singaporean.

Constance: Also it’s an important event in civil society activism—everything I have done, every book I’ve written has been a civil society active responsibility that I was meeting. That it was important for people to remember this history. So it’s not just the Saga I’m covering, I’m covering a lot of political, social, cultural events that have affected our lives and have made us who we are today. And why I, the 86-year-old civil society activist would say, “Here we go again.” That shouldn’t happen. That shouldn’t be repeated. We shouldn't normalise it, we shouldn’t accept it.

Balli: I think the memoir is very triumphant in getting that message across. I wanted to ask about your memories. You write with such clarity about your memories; how did you excavate them, and were there any obstacles you encountered in trying to draw out those memories? Because you have very vivid memories of childhood, of India, and of your later years in Singapore and also your years in Melbourne. You’ve got a really keen sense of detail. There’s this one particular scene that I really like with the dog that used to follow you in Melbourne and was kind of your companion, and there were just lovely anecdotes like that that were sharply realised. Are there diaries that you kept over the years, were there pictures? And how did you select memories as well?

Constance: Because they were my most memorable memories. They were happy memories. One of the things I did as I began writing 10 years ago was to draw up a timeline from the year of my birth and every year subsequently what was I doing and where was I. The historical references of course you can always go to Google, it’s such a great companion. So that’s how I remember. I do remember them vividly, maybe that’s what it is when you grow older, those memories come back more sharply than say maybe the question you asked me five minutes ago. I wouldn’t remember that.

Balli: Was there a particular selection process that you had to go through, cause surely some memories emerge that we maybe don’t want to share or don’t think are significant enough. What makes a memory bright and significant enough to put in a memoir?

Constance: I was trying to chart my life as a person to the time I became an activist. I was looking at or trying to remember times in my life, experiences in my life that led to that. Most of the time I think that’s what I did. Some of the times, it’s because something happened, like the dog story, which was so unusual and I began to have a new understanding of animals, that they’re sentient beings and it amazed me. That’s why I remember it so vividly.

Balli: It really was a beautiful moment and there are lots of beautiful moments in the memoir. I wanted to ask as well about the way you incorporate writing from other writers, from essayists, from political essays. You’ve got a wonderful quote from Virginia Woolf quite early on. You brought in all of these different disciplines and I wanted to ask about the motivation to do that. Where did that come from, was that something that came as you were writing and did you go “Oh, this reminds me of that!” Or was there a more conscious study of these things and then weaving your memoir in with them?

Constance: One of the things I did was of course to buy a lot of books. And memory is triggered by a word here, an anecdote there that you read in somebody’s writing. You remember “this happened to me,” and you make the connection. But of course in essay writing, you have to substantiate or reinforce with an authority figure. So what I’m saying may not be accepted but I quote an authority figure as we all do when writing essays. So that’s one. Another reason is that sometimes they say things much better than what I can say or how I can say it. They say it so well. So sometimes of course it triggers ideas as well, and memories.

Balli: Yeah, I really enjoyed that in the memoir. As a reader I had a sense that I was following you through your life, when you talked about it it was quite intimate and personal but when you brought in these other writings, it made your life so much a part of the world, and there was so much context that came from it, I think.

Constance: I also put in context about Singapore happenings, the wider world of politics, and how the wider world of politics influenced some of the decisions our political leaders made, especially in the use of the ISA (Internal Security Act). That was important to me and I wanted that recorded. But there’s a part of history that I didn’t know anything about, which I found interesting because as a teenager and young adult and we became independent, you accept the stories you’re told. So later on, I started meeting individuals who’d gone through the Chinese system and attended the Chinese universities, and I began to read up on that. So that was important for me.

You know you have all these politicians, and all of us do it too. We narrate the story from our own perspective, from our own motivations, and I found the story of the Chinese students, the Chung Cheng High School, all of them protesting outside the Istana because they didn't want to be drafted by the British government. All those stories gave me a new understanding about our political life, and the political life of the early history, which I had accepted as the truth. So that was important, there is always a different story to tell and we need to know those stories, to better understand ourselves.

Balli: That actually segues very nicely into the section here about place and identity. You write with a really strong sense of place and I wanted to know if having distance from places enhances your writing about those places or enriches your sense of place. For example, was it different to write your memories about your childhood in India or years in Melbourne compared to writing about present day Singapore? Was there a difference in terms of where you were when you wrote about those places, like did that distance help you to understand the places differently?

Constance: I was very fortunate I had those experiences, because it’s experiences of another culture, more humane culture. I found that to be a happy place to be in. I suppose in India during the war it was village life, and the village is full of relatives, and I remember somebody writing in a book, you need a village to raise a child, and I was lucky to have had that experience, to know the connections between people, to know connections of people who can love you unconditionally and accept you. And those were important memories for what I turned out to be. It’s just come to me, I’m very good at organising people as some of you know very well. I have over the thirty odd years of my civil society activism, organised a lot of groups, and I often wonder about it. Now I see the connection. It’s your experiences in life, besides the fact that I’m the eldest of 9.

But I see the connection that you do need a village, and I often tell people who are interested in organising civil society groups that what you need is to begin with a conversation around a table. And you build that, you need that community for the kind of work you’re going to do, for the kind of life you’re going to lead, you need a community. You have to nurture that community. I learnt that when I was a child. Thank you for asking that question. It just dawned on me.

Balli: Well it is quite a global village that you have in particular as well. You said you have 8 siblings, you’re one of 9. You get that sense, reading the book. There’s always the sister in Perth or the nephew in Germany. You always seem to have someone you’re talking to that’s part of that life and part of that context for you and that must have played into it as well, in terms of having that amazing global community just within your family.

Constance: I have a brother. I do mention him in the book. I don’t think he read my book. I’m going to make him feel guilty.

Balli: There’s also, even within Singapore, I wanted to ask about the retreat at Marymount convent house. You mention that’s a very special place and a place that helped you recharge in a way, and just connect with yourself. I wanted to ask about journeys away in general.

Constance: I think every now and then after the Saga I went to the retreat house and the retreat sister is the one who suggested I write this book. I think it’s important to get away and rethink. Of course there were existential questions I was asking, and I could talk about that at the retreat house. I’ve been to retreat houses several times, in fact I’ve been to one in Melbourne too. Usually it’s at some crisis point; you want to get some clarity. Actually you never get that clarity, you ask those questions every now and then. But at that moment yes, you say okay each day is important, you live each day as fully as you can.

Balli: That was actually my next question: Is there ever a moment when you do get that clarity? There’s also in the memoir a sense of conflicting loyalties that I think a lot of us are familiar with especially those of us who straddle different countries, different cultures, where when you’re within Singapore you advocate for the marginalised and you can say there’s censorship and all these things. But then when you were in Australia, your sister said something about Singapore being too oppressive, and you got into a big argument with her at the dinner table. Or someone who said something about Singapore being a police state and you got quite indignant about it. I was wondering if you could speak to that tug of loyalties.

Constance: Nobody criticises my country, I can criticise my country. And there’s something else too, is that outsiders can see us more clearly than we can see ourselves. That’s something I learned too, they may make those comments which irritate and upset you, but they are telling you something about yourself that we don’t see because we live it. We need to see it. We need to be told or talked about and that’s important I think.

Balli: But first we tell them to be quiet, we say no, it’s my country. I think that's fair and that’s a very natural reaction, I was very glad you put that in the memoir. It made me feel a lot less alone. We’re going to go into the personal and political now, I think you’ve alluded to it. The memoir itself reminds us that the personal is political. Can you speak to how individual stories help us to understand a state, its histories and perhaps its shortcomings as well? Because that is your coming of age, Singapore’s coming of age, those parallels are so clear in the memoir and that’s what makes it such compelling reading.

Constance: Well, the current controversy about this book and The Arts House involvement and your involvement, that's a personal story. You made it political by speaking up on it. And feminist history is full of those kind of political stories, the personal stories which have become political. You politicise it in order to make changes. You have to make it public. I remember people used to get really annoyed with us when we first started AWARE 30 years ago, when we started talking about domestic violence and the Graduate Mothers Scheme and all that. “Why are they so loud?”

But unless you speak up, and make it public, people won’t think about it. You need people to think about it in order to change attitudes. One of my objectives in writing this book is also, it focuses on civil society activism. Whatever you might say, the changes we see now, are changes that women have worked through. And civil society, like the environmentalists, the nature societies, they have worked at it, they have fought hard to make those changes. Things don’t just happen by themselves.

We have to speak up to make it happen. That is an important lesson. And I do give examples of successes of civil society activism and how it has changed Singapore and how it has made a difference to our lives, even to our individual lives. People talking about poverty, Teo You Yenn’s book on what poverty [inequality] looks like, and a whole lot of books that have come out as a result of research.

I remember I think in the 1990s when our then Prime Minister was into nurture and nature and eugenics, and he wanted to prove that certain groups of people are poor because of their race. And he asked a friend of mine, Myrna Blake who is no longer here, who was a professor at the social work department, to do a study. She was the pioneer in the kind of study that You Yenn is doing now. She interviewed individual mothers and came up with the story that it’s not their genetics, not their race, it’s the circumstances of their lives and that they cannot, no matter what they do, get out of it.

And history repeats, generation after generation. A mother who has disabled children, a single mother who for some reason or other has become single. It’s not because she’s Malay or Indian or Chinese that she’s poor, but because of the circumstances of her life. And she proved that with her study. So yes, personal is political. But of course, it has taken us 25, 30 years before we even started talking about poverty in our community.

Balli: I think there is also a prevailing idea that if you question somewhat or you’re somewhat critical of something then you’re–it’s kind of an all or nothing. If you’re a little bit critical then you must be critical of all, it’s a very all or nothing approach. You’re either here and with us and you’re following the narrative, or leave, be quiet or something. That’s the thing, I saw a lot of nuance in your book. I saw your opinions, you didn’t sugarcoat them, and I really liked that. But there were also times where you're really appreciative of Singapore. You talk about that at the end of the memoir, that you actually appreciate the skyscrapers, you have an appreciation for capital, in a way that you haven’t before, which was surprising. I really enjoyed that there was this change as well in your perspective.

Constance: I haven’t changed, I’m a socialist. Capitalism has some advantages, it’s just that we have followed an extreme form of capitalism.

Balli: And you’re also not entirely critical of Lee Kuan Yew. There is a moment when you talked about him, I got a little bit… you mentioned his “Peranakan good looks” and his "great charisma", and I thought, “My goodness, what am I reading?”

Constance: He spoke so well, he was a very good speaker.

Balli: I suppose you’ve already approached this question, why don’t we get right into it. The memoir contains some criticisms and some questions about the state’s approach to race and language. You particularly lament the top-down approach towards imposing national identity, the CMIO structure and all that just siloing us. Why were these important points to make in your memoir? And did writing about Singapore’s identity give you more insights into your own individual identity or vice versa?

Constance: One of the things, I mean racism and classism won't go away, they’ll always be there. But in our society, our political culture, everything is in your face, and that’s the difficulty with coping. Because when you institutionalise racism, and by that meaning your IC for instance, it’s divisive. People can only think in terms of race. So it was important to talk about it, and it took the Indians many years to talk about it. And I can tell you that, the way we interact with each other, even the racist attitudes, the excluding of people of other races in your office group, for instance, we take it as normal.

And the Indians and the Malays don’t talk about it. And because they don’t talk about it, you don't know that there is racism. And we learnt that you have to talk about it. And I have friends who would deny that and I’d say okay go and ask your Indian friends. They come back and say yes, because the Indian friends would not have talked about how they’ve been treated in the classroom. So it was important to talk about it, it makes us feel uncomfortable—especially the majority, it makes people feel uncomfortable but it’s essential. It became a public debate.

Which is important for us to think about the way we treat other people and the way we interact with other people. What is sad about it is how mothers sending their children to kindergarten and to primary school have to prepare their child—if you’re an Indian child—About how to deal with these issues. And that is really sad. So I think we need to talk more about it. It's not a pleasant subject. Look, 250 years or 700 years of history in Singapore was multicultural. The British made the divisions between the Chinese, Malays and Indians. Why did we as an independent country have to carry forward? We didn't, and we should question that, we should challenge that. So that’s our responsibility.

Balli: Thank you. I agree. I think the trouble with the way that racism is defined for us in our national narratives as well is very extreme. It’s race riots, or violence, so a lot of institutional racism, a lot of microaggressions, a lot of everyday things that impact people don’t get talked about.

Constance: Yeah. I have a story to tell. There was this young Indonesian man, who had been working in Singapore and he wanted to bring his family over. And in Indonesia, India, Australia, you don’t have a category ‘race’. It’s your nationality. You're Indonesian, that’s it, you’re Indian, full stop. So when he went to immigration to apply for citizenship, he had to fill that column. He looked at the immigration officer and said, “I don’t know what my race is, I'm Indonesian.” So he said, and this is a true story, the immigration officer said, “Why don't you put yourself down as Chinese, and you’ll get your citizenship very quickly.” So now there’s this Indonesian man who doesn’t know what he is, who’s now labelled as Chinese. So we know that race is a label, it’s a social construct.

Balli: And an official was telling him how to rig the system, “just take that one, that one you’ll get benefits.” Wow, this is actually a good way to segue into the question I have about disillusionment. You speak of disillusionment, there's a strong sense of injustice in your writing, as a woman from a minority race in Singapore, I wanted to ask about the writing of that, because obviously there is this need to talk about those things but also the need to write your narrative, write your story, and how do you balance that without veering into something that sounds like a speech or an op-ed. You want to weave it into your story and you also get your point across, so how is that process like for you as a writer?

Constance: It’s important to remember that I've lived a long life. And that the first election I could vote and as I said Lee Kuan Yew was a very charismatic leader and so was the whole cabinet. I was a fan! And what he promised was a democratic socialist state. They began with that, the women’s charter was in their first term, and equal pay for equal work and so on. He promised a multicultural—he used that term—it veered into multiracial 20 years later. Multicultural society. And then what happened?

He silenced his civil society, which by the way I didn't recognise then. I thought they were all communists who were being interned. It’s only in 1987 when the Marxist conspiracy was right in front of my eyes with my friends that I realised that it’s so easy to make up stories. That's when I became very skeptical and cynical about our politics. I feel disillusioned, I feel betrayed. For many years I voted the PAP—confession time—There were lots of times I didn't have the opportunity to vote because it was a walkover. So yes, I feel betrayed.

Balli: But you also speak at the end of the memoir about living in a constant sense of wonderment or amazement. You talked about little things, little details you see in nature or looking out your window and the scenes before you, and that you live in a constant sense of amazement. How does that square with the disillusionment?

Constance: You can! I mean, one of the questions you asked was about travels abroad and coming back to Singapore and how you live this reality, you know? When you travel abroad, you realise the things that you love. What are the things that make you happy? Because you have time, you’re on holiday. Here, the life is so intense, you don’t have the time—I now have the time, which is why I'm writing about birds! That’s what I mean when I say our intense kind of capitalism doesn’t let us lead a human life, things that will make us better people, compassionate people, we don’t have the time to think about those issues, because every day is a battle, is a struggle. You feel that as soon as you touch down in Changi airport, you feel that intensity, so you have to find ways of finding joy.

Balli: Thank you. I think that’s a wonderful place to finish our conversation before we go into questions from the audience. A question from Arun: what in your view is a potential danger that the next generation of civil society activists will need to tackle?

Constance: I do write about that in my updated version. And I think the danger is that we have normalised our culture. Which is why it's important to read stories—why it’s important to read my story. In spite of POFMA and FICA and whatever else, I see young people coming up and talking to me about “how do we organise activism?” “What can we do?” The sense is not that they don’t want to do it. The sense is not for the lack of civic education in schools and the public domain, people don’t know what to do. They have passions that they want to work on.

My suggestion: get yourself in a group, have conversations. You empower each other, empower yourself with knowledge, with understanding of our history. That has been my advice: get together and have conversations with like-minded people. Or if you are passionate about something, join an organisation that is already in existence. Which I find young people are reluctant to do—they all want to be leaders and organise stuff, but you need a lot of soldiers as well to get the work done.

Balli: There’s a question that relates to that quite well–We have seen civil society activists that have stepped forward to become MPs/NMPs. What are your thoughts on this and from your point of view, have they been effective?

Constance: Which brings to mind that image of the speaker telling Leong Mun Wai to shut up. He was raising questions and it's hard work being an MP and NMP, it’s hard work. Sometimes soul-destroying. But I think we have to do it and that's part of our responsibility as civil society. Some people can do it, some people can’t. So those who can—yeah. And they will change attitudes and the culture. As more and more people join the political domain and become active it will have to change. They have problems, we don’t have a prime minister. so they will be forced to change their politics.

Balli: Most of the questions are in this vein, I’m trying to find something about the book and writing. Bharati has asked: Civil society “anger” hasn’t made a substantive enough difference to how the Singapore establishment conducts itself. What’s your perspective on this statement?

Constance: I think you have to read my book. We have made a difference and civil society has made a difference. Slowly the political establishment will have to change. We know we are at a crisis point in terms of leadership. And unless their culture changes, we will be.

I don't like the word anger—we are passionate. Oh yeah that’s right, I did say that [it’s important to be angry] didn’t I! We do need anger to energise ourselves. But I remember when we were beginning those years, people used to demonise us. And that I think is wrong, it’s misunderstanding our civil society activism, just as it’s a misunderstanding of feminism and civil society, what else? Politics. We have such a narrow view, a narrow sense of what these terms mean. And that's got to do with the lack of education.

Balli: I can’t remember if it was in the memoir of something that you said in the early days of AWARE there was a man who said “Stop doing this, why are you turning our daughters against us, our daughters are lovely.” I thought that was really interesting, like AWARE’s focus was to make people less lovely. But then there was also a really nice anecdote from the memoir about the taxi driver who wouldn't take money from you when he found out you were from AWARE, because you all have done so much for women.

Constance: Lilian and I were in the taxi, we had come out of Holland Village back to AWARE after lunch, and the taxi driver wouldn't take money from us.

Balli: That’s lovely. A question about racism: You mention the importance of talking about racism. Online these conversations can get very ugly. How do we debate with civility? Is racism even a debate?

Constance: Again I go back to the image of the speaker telling one of the elected MPs to shut up and sit down. He was very very rude, I thought. One of the reasons that we are unable to talk politely—We’re not very articulate because we’re not trained to be articulate in the school system. If a child speaks up, that child is demonised as troublesome. We don't have the practice, the language, the vocabulary. All that comes from more debates, more education, and conversations. Then we will learn how to debate diplomatically, we will have the language to express ourselves. It’s when you don't have the language to express yourself that you become a bully or you sound rude, because you don’t have the language. And that is our main problem, but there will always be rude people.

Balli: And the lack of nuance—I agree that our education system, we don't have practice in these conversations, I think lack of nuance is something that we see on social media. In many other societies as well, where they are well-versed in talking about race, you do have ugly things being said and a real flattening of ideas. Ah! Here’s a question about the book: Would you consider an audio book of any of your books? It would be lovely to hear you voice as we walk through your memoir.

Constance: It has been suggested.

Balli: So you have considered it?

Constance: I think I’ll be very tired.

Balli: You don't have to read it all in one day is the advice from your friends.

Constance: I have to confess, it’s not my ego though—maybe it is—The current version, updated, edited, has been done very well. I had to sit through and read it through, and I enjoyed it! I thought it was very easy to read.

Balli: Is that your practice? Do you read your work out loud to yourself?

Constance: No, I’m just reading silently.

Balli: Recently many independent arts/education spaces & media outlets have been closing/shut down. How does this impact the future of Singaporean civil society?

Constance: I think it’s happening because of the pandemic, it’s happening all over the world, there isn't enough activity to sustain. But it will come back I’m sure.

Balli: You’re quite confident about that? You have faith in that?

Constance: I have faith in that. There are generations of young people who are more interested, who are more creative, who have more experiences, who have travelled and so the experience of a different world, from what I've seen there’s a lot of activity. And the fact that we have—which is a great thing, another thing we have to rejoice. SOTA for instance, schools that promote art education, art and creative subjects. Which is a good thing. And I have seen, I have been a participant, I think it's happening, it's just that we don't seem to have enough publicity. We don’t talk about this much. But it is happening, young people are very enthusiastic, so it will happen. The only thing that is a problem, and the problem has to do with the lack of resources, is the lack of independent spaces in Singapore.

Balli: Leads very nicely into this question, which I lost just now but now found it. As civil society, often we'll work with the Government for support/a platform or to enact structural change, but not everyone is on our side. How do we manage that?

And there’s also a question that links to that:

How do activists today work with the restrictions placed upon us, like for e.g POFMA. So being an activist but also having this codependent relationship with the structures around us.

Constance: But that’s true of everywhere I think, it's always the tension between governments and civil society and you have to negotiate that tension. As I said earlier, our government is in our face. So it’s more difficult, which is why the conversations and the select committee hearings are important. We don’t see the unintended consequences of these legislations. And what is dangerous is that it depends on the view of one particular person—the minister or whoever. What’s important is that we are critical of people who stand up and question, for instance, Jolovan.

People make fun of him, “why is he doing all these silly things?” Or PJ Thum, or Kirsten. You should read them and follow them, it’s another point of view that you need to understand. Now Jolovan can stand in a public place with a blank sheet of paper and he will get arrested. That's ridiculous and you should say so, more of us must say these things. And of course if a policeman sees Jolovan standing with a piece of paper, the policeman will say he’s up to some trouble—“I don't know what trouble but he is troublesome so I have to arrest him” That’s how our law works and we have to speak up.

So every time we laugh at somebody—when we started 32 years ago at AWARE, we were laughed at, we were demonised. We were the ones who were speaking up then. Kirsten, Jolovan, PJ Thum are the current generation, they’re braver, better educated and they are more confident than we—I ever was. It’s the support from the community that’s important.

Balli: It’s worth mentioning as well that people like Kirsten, Jolovan, PJ, they’re all individuals working on their own, so I imagine it’s a very lonely place to be when a lot of people are poking fun at them. Whereas you had AWARE, you had I suppose safety in numbers.

Contance: We had a community of friends and supporters, we could empower each other.

Balli: Do you think community is important to activism in that sense?

Constance: It is very important, it’s lonely otherwise. How long can you take this kind of treatment from legislators? They need our support. Jolovan wrote on Facebook after your statement that he was going to write a letter to the minister, he was challenging the censorship. And I remember we were talking about racism—there were incidents of racism. One of the things that was suggested, you see, civil society doesn’t mean you have to stand and wave flags. It can mean you writing a letter to your MP. Telling the MP you don't like this happening. We are not supporting this. That itself is an active citizenship responsibility. You don’t have to do major things, you don’t have to go out and make speeches, just that is important, and we don't do enough of that, we don't do that at all.

Balli: You spoke about how a turning point for you was when your husband was in hospital and you wrote a letter—Was that the first letter you wrote?

Constance: No, years before that, Lee Kuan Yew made a comment about Indian culture. “If you’re not a Hindu then you’re not Indian, you don't have Indian culture in you.” so I wrote a letter telling him that my mother would be very upset, because she has 500 years of Catholicism in that part of Kerala, and she thinks of herself as Indian and nothing else.

Balli: It’s good to end on one more question, to conclude this on, about joy. Someone asked about what your most joyous moment as an activist was.

Constance: I remember in our early stages of the campaign against domestic violence and rape, I was in this national council, I was the only woman there and I used to bug them about statistics, and they said “why don't you write a report”, so I did. Nothing came out of it. Three months later, I sent it to the minister, I sent it to the police chief, I sent it to the Chief Justice. Nobody responded. And then, the Singapore Broadcasting Corporation, their main news was at 7pm. They rung me up, about something happening elsewhere, and they wanted my comment about domestic violence. And I said “You know, we submitted a report to the council three months ago but we haven't heard anything from it.” That came on the 7 o'clock news that day, and the next day it appeared in the Straits Times, page one. Within the hour the commissioner of the police rang me up and said, “Constance, can I have a copy of that report? I had misplaced it.”

Balli: Well done. I can’t think of a better anecdote to end this conversation on. Thank you so much for your time, for this book and for all that you’ve done for Singapore.

Constance: Thank you.

About the Speakers:

Constance Singam is a writer and civil society activist. Constance has led women’s organisations, co-founded civil society groups, been a columnist in national publications, and co-edited several books. Her nonfiction works include Re-Presenting Singapore Women (2004) and The Art of Advocacy in Singapore (2017). She has written two memoirs including Never Leave Home Without Your Chilli Sauce (2016), and three children’s books including Porter the Adventurous Otter (2021). She was inducted into the Singapore Women’s Hall of Fame in 2015.

Balli Kaur Jaswal is the author of four novels, including Singapore Literature Prize finalist Sugarbread, and Inheritance, which won the Sydney Morning Herald's Best Young Australian Novelist award. Her international bestseller Erotic Stories for Punjabi Widows was selected by Reese Witherspoon's Book Club, with a forthcoming feature film adaptation. Besides fiction, Jaswal has also written essays and op-eds which have appeared in publications such as The New York Times. She is preparing for the 2023 release of her upcoming novel.