"Do you sever a tie, and is that a form of caring?" | Book Launch of Potong: To Care/Cut

The book launch of Potong took place on 22 May 2022. You can access the full transcript of the programme on this page. Portions of the transcript have been edited for clarity.

About Potong: To Care/Cut

In Johnny Jon Jon’s plays, seemingly ordinary events are turned into hauntingly profound exchanges when the individual’s sense of self comes under scrutiny.

In Hawa, a new Muslim convert finds herself tasked with overseeing the funeral arrangements of her partner.

In Potong, a son is sent away by a mother to return to Singapore to undergo the coming-of-age rites of passage that await him: circumcision and conscription.

You can find the speaker bios at the bottom of this page. Enjoy the conversation!

Photo of launch. Left to right: Johnny Jon Jon, Irfan Kasban, Jamal Mohamad, Nabilah Said

✂️

Nabilah: I just wanted to briefly talk about the speakers, Just to contextualise Irfan and Jamal’s involvement. Irfan actually directed Potong, which was staged in Malay Heritage Center, I’m gonna start with my first question. Hawa was first staged in 2015 presented by Hatch Theatrics. Brought to Australia in the Brisbane Festival. It is important to set up this information. So it’s just important to think about this journey from page to stage and from stage again.

Jon Jon, my first question to you is that your plays cover themes like religion, gender, sexuality, and really many more. And maybe there’s a tendency to call them blank plays - a religion play, or a sexuality play, for example. But actually you kind of mix the themes together in way that are complex yet relatable in a way that only you can. So how did you come to write Hawa and Potong and what were you influenced by?

Jon Jon: So for Hawa: My aunt passed away and there was a family friend who came to the funeral and he decided it would be okay to video record the entire process up till burial. And in the end he actually gave the family a DVD. I thought that was kind of interesting. We never really saw it as a process to be observed but rather as a rite to be observed, if you get what I mean. So that was funny. And also because I spent time abroad. I went to Canada to study Quranic studies. That was when I realised that actually there is a different version or a different perspective to my faith, a more compassionate, more forgiving God.

And when I came back there were a lot of very harsh conversations about the LGTBQ members, I kind of felt that–there were lots of discussions that led to the creation of Hawa. I think one interesting thing was that, I was sitting in the corridors of NTU, and there were these two conversations that really got me interested to write Hawa. One of them was from a group of guys who said like “Hey let’s go to NTU Muslim Society and get together, because there will be chicks there.” And I thought okay, that’s a weird kind of intention right? And there was another conversation that was between a convert and a born Muslim–I assume born Muslim. And she said, “even God waits until the end of time to judge us all so why are we in such a hurry to judge people?” That was what drove me to write Hawa.

With Potong, it was simpler and clear cut. I met a lot of people in the police force who were returning from overseas to serve NS (National Service). And they all had very interesting stories about how they integrated back into our society. I was also going through a period of loss; my grandfather was going through the final stages of Alzheimer's. So a lot of the inspiration came from my conversations. Not many but a lot of my interactions and conversations with him. Sorry, I took so much time just to explain!

Nabilah: Oh no it’s okay, that's why people are here! I think you’re going to say sorry a few more times, so bear with us. So maybe just to talk about the two plays in case the audience is not familiar. Hawa is a dark comedy about a Muslim convert who has to manage the funeral rites for her same-sex partner. And there are also other interesting characters who are also flawed in their own rights. And then for Potong, it’s about how a family deals with displacement, estrangement and sacrifice, but also, like Hawa, dealing with queer identity, sexuality, religion and family ties.

In Potong there is also a trans character and Jon Jon manages to weave that in in a very natural and humane way as well. And I think later we’ll see something to that regard. But maybe bringing in Jamal and Irfan, what do each of you like about Jon Jon’s voice or what has he not said about his voice or his practice that you find interesting?

Irfan: I met Jon Jon in 2006 when we were competing at Teater Ekamatra’s programme. And we were dubbed the rivals. And right after that we went for a playwright mentorship by Alfian Sa’at, and I won.

Jon Jon: That’s debatable.

Irfan: From that mentorship, Rendevous Point came to exist. That was the first time we were going to collaborate. It was tough, the characters and absurdism were not in my vocabulary yet. But I still did enjoy watching it. I was trying to make sense of it rather than allowing it to exist in free form. Sorry what was the question?

Nabilah: What do you think about Jon Jon’s voice?

Irfan: Oh I love it. He brings this magical absurdist voice. You can’t believe it happens. Like in Hawa, there’s this one character who’s just a guy that likes to go to funerals.

Nabilah: To pick up girls.

Irfan: Yes, to pick up girls. And it’s ridiculous… the voice is so precise that you believe it’s real.

Nabilah: I wanted to slap him.

Jon Jon: Well, some would have slept with him la, so…

Nabilah: Alright, moving on. Jamal, what about you?

Jamal: I had to take over you because you couldn’t direct his play. The reason why Irfan won Pesta Peti Putih compared to Jon Jon, like you said, it was debatable. Two of us who were judges on the competition, we liked Jon Jon’s work but we recognised that Irfan’s work was more accessible. Jon Jon’s work was chaotic, it lacked structure, it was insane. So when he wrote Rendezvous Point, same thing.

If you ever read his scripts, he refuses to tell you where they take place. He refuses to tell you where the scene changes are, or where they might be, where the actors are located, what space they occupy. He refuses to give you any of these tips. So you have to interpret what he's trying to say. That was the challenge Irfan had. Irfan at that point as a budding playwright, he didn’t really have the vocabulary, he said. To be honest nobody did! Nobody had the vocabulary to interpret Jon Jon. I was lucky because I was familiar with Effendy’s works, I was more familiar with some of the more absurd stuff Ekamatra has done in the past–not working on them but watching them and reading them.

So when I read Jon Jon’s script, images started coming to my head, I sat him down, I talked to him and said this is what I wanted to do. And what I did, I think, can be rude to some playwrights? Because I put him in boxes, I had to structure this guy because he had no structure and I had to structure him. And at the same time, allow the story to flow from scene to scene. So it’s like a dreamscape when you’re working with Jon Jon’s play. So you have: at the start they’re in their respective bedrooms, suddenly they’ve jumped into the jamming studio, suddenly they’re at the makan place together.

And none of this was told to you. He didn’t put it in the script at all. The conversations just flowed. So it is dreamlike. I really enjoyed the process, working with him. I enjoyed the voice, I enjoyed the stories. Alfian Sa’at came to me after the play, and he said “I don’t know what that was, but tonight it worked.” Of the three nights we staged it, only one night didn’t work, because the actors didn’t have it together.

So I love his voice because he allows us the room to interpret it, he allows the actors room to interpret it. So if you read this, good luck because you might have dreams or nightmares, because it’s something that will play with your mind quite a bit.

Nabilah: I think I read some early reviews of the book in which people said that they ended up thinking of a lot of these themes in a deeper way, even kind of surprising themselves from when they first read it. When you first read it, you think you know it, and then there’s a lot more there. Kind of like the layers.

I think just to add to that, because I’m also a fan of Jon Jon’s, and something that was not mentioned is his wordplay. I think his wordplay is out of the world, you almost want to slap him also because he goes there. He goes there with all the jokes and things that are on his mind, he puts it on the page. He challenges the audience to like… this is what it is, will you accept it? Will you go on the ride with him?

I think on that note, we can introduce the scene that we are going to be watching from a recording of Potong. Irfan, tell us more.

Irfan: So I chose this scene. It is the second time the main character, Adam–who is tasked to go back to Singapore to serve his NS (National Service), he’s supposed to do his circumcision–this is the second time he is at the office with Dr Dini, and he has brought his uncle/auntie. I think this is where we hear the beautiful humour of Jon Jon.

(clip plays)

Irfan: I think that shows how these three characters in real life would be a really beautiful chance, like you would never imagine that these three characters would happen. A female circumcision doctor, a trans woman and a half-white nephew.

Nabilah: Just now you were mentioning magical realism right, so I was wondering Jon Jon, do you ever strive for realism? Or what is that world that’s in your head? How would you describe that?

Jon Jon: To be honest, whatever I think about when I write, I feel that it should be realistic. Because otherwise when people watch it, I don’t want them to feel like “oh, this is just another part of his imagination. It’s not real. Somebody out there is not experiencing it.” I think that’s my responsibility as a part of… as a practitioner within the minor literature. I think it’s realistic. It’s just that, in some sense, when people see–maybe because they have not experienced such situations, they think it’s absurd, but I assure you, in some sense it must be real.

Jamal: I disagree. Each of your characters are very natural of course; the situations you put them in right, at the funeral, and then you throw in this guy who goes there to attend dates–that’s absurd. You are mixing them together and pushing them to communicate and discuss things, and that’s absurd. That’s what makes you very interesting because you think that’s natural to everybody else.

Jon Jon: Yeah.

Nabilah: Let's go back to the book. It’s called Potong: to Care/Cut. Can you describe–because I understand Ethos Books chose that title, and for you, you had submitted Potong and Hawa together for them to consider. So what was the discussion like about this title of the book, and what does it mean to you?

Jon Jon: So when I submitted the manuscripts to Ethos, I actually thought they would be considered separately. I didn't see Hawa and Potong to be part of the same body of work, because I was working on Punggah, and in the future Potong, which I felt were the three P’s–uh, the three pieces–that will form a trilogy of sorts. When they told me that “We think it will be good for them to be put together because of the duality that exists between the two plays,” I was quite stoked about it. Like oh wow, someone actually saw a different quality to these two plays, which I thought was quite interesting.

And when they came up with the proposal of the title, they actually asked me to think of a title, and I just couldn’t. Because even for me, I couldn’t see the similarities, even though they told me there were similarities. And they proposed “Potong”, and I thought that’s pretty… on the nose. And so I really agreed with it.

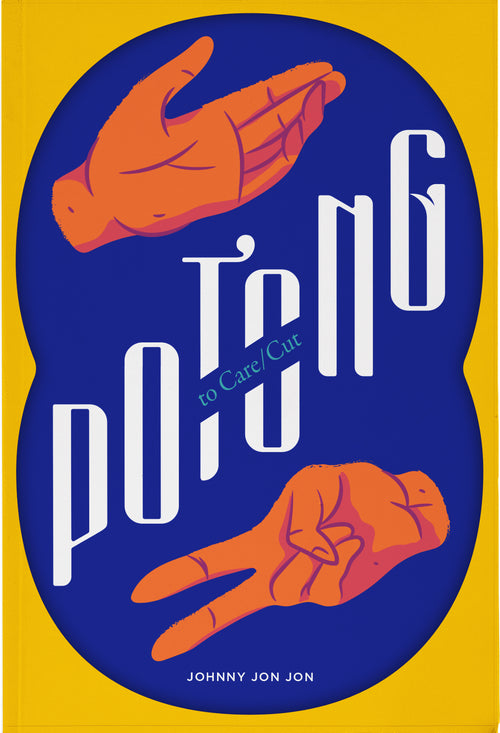

Then eventually when the cover design came out–so there was something that I didn’t share with a lot of people. I think even my wife didn’t know about this practice. When I write my scripts, I actually draw tarot cards as part of the framing of the characters or the framing of the plot, you see. When the design came out, there’s a bit of a tarot influence; there is a duality to each card right? And I thought wow you guys really got your work done really well. Yeah, so that’s how it came about.

Nabilah: It’s pretty interesting because I think as a playwright, you think of your plays as kind of singularly, right? Like each play you write it and there’s often all sorts of things that’s going on in your head as you focus on one play, so like you said, you don’t often see them together as any kind of companions. They’re not companion pieces in your head, but as a book it kind of is.

Jon Jon: Yeah. The only thread that cuts across is usually the characters, and also in a sense the proto-characters. Every character in every one of my plays, they start off as Siti K. Whether male or female, it’s always Siti K.

So when it comes to even naming conventions, I used to think that names were really important. ‘Cause I wanted to be Shakespeare, right? Oh Mercutio means something, I need to make sense of it. But I realised that I could keep it simple and people could connect that this character could actually exist in another one of my plays, and it could be the same person, or it could not be the same person, but it… yeah so to me there was that transcendence that I was thinking about? But it wasn’t something that I was trying to hammer home.

Nabilah: So I think we have to contextualise this for people. So Siti K is Siti Khalijah Zainal, who, I think a lot of people would know from theatre.

Jon Jon: Or NDP (National Day Parade).

Nabilah: Or NDP?

Jon Jon: Yah, because she’s always the cheerleader for the pre-parade section, right.

Nabilah: Okay. And so you’re very inspired by her as a performer, and you said that everything you write is like Siti K is whispering in your ear?

Jon Jon: Yeah. So she’s the only woman that my wife allows me to listen to other than herself. So yeah.

Nabilah: For Jamal and Irfan, what do you think about this title, Potong: To Care/Cut? Or what does it mean to you?

Irfan: Directing Potong, the play, I think the theme that was very clear was do you sever a tie, and is that a form of caring? Like one of the characters was Siti who was the mother who stayed back in Australia, because she was going through early onset dementia. So the idea of Potong was to send the son to Singapore and let him go through his rites. So it was a question of love and is that love–because there’s the comparison with the family in Singapore right. Siti’s mother was in full dementia, and thinks that her son is her daughter.

So Siti who was in Australia doesn’t want that to happen to her son, so it was a very beautiful juxtaposition.

Nabilah: As in you’re talking about cutting as like forcing a kind of separation out of love?

Irfan: Correct.

Nabilah: And we see it in Hawa as well, in the sense of a family that has to separate because of certain beliefs and non-beliefs as well.

Jamal: I think it’s also quite tricky for English audiences to fully comprehend the nuances that come with the wordplay that Jon Jon uses. Potong means to cut literally, but it also means other things. Like when he did Hawa, Hawa is the first woman, or woman, it is also temperature, it is also your desires. So to translate to English it sometimes becomes–it can become nonsense. It's almost like translating a pantun.

When you translate pantun you can’t really get it poetically correct, or contextually correct. The accuracy is very hard to get in English. So I think Ethos Books did a good job to sort of tease out this wordplay that Jon Jon includes in his plays even though it’s impossible to do so, to translate what “Potong” means in the play. But “To Care/Cut” sort of begins that suggestion that there is a deeper meaning to it..

Nabilah: A conversation. Jon Jon, you say you write in English first? Can you talk a little bit about that?

Jon Jon: Yeah. So my process is that I will write everything in English first, because most of the plays I’ve watched Siti K in, they are performed in English. So she will speak to me in English, and I will have it down in English. And then I would start to see things where I feel like “hey actually this is better in Malay,” and then I would give it a different treatment. So certain things I would have to sacrifice, because in English the context I was going for is really different from the Malay, but that’s what I would focus on.

I will usually not return back from Malay to English thereafter, unless like a sponsor says “your text is too English, need to be more Malay,” then, shucks. Or it’s too Malay and need to be more English, then okay, I will change it. But otherwise I don’t, like even when it went to Australia, for Hawa, I didn’t do a lot of changing from Malay to English as well, because I felt like the ideas or rather the feelings we were trying to convey were just better in Malay.

That’s why if you look at Potong, a lot of the scene titles I decided to choose are non-English words. Primarily Japanese, and one Portuguese word. And that’s because I feel that some feelings are just captured better in a different language. And just because it’s in a different language doesn’t mean you are unable to access it, right? Yeah. I feel that some feelings are just better captured in a different language.

Nabilah: Cool. So kind of like thinking of the publication of it. You and Ethos had to make a lot of decisions about where the surtitles would be, and things like that. For you, what was most important in terms of creating this piece of text that is now a book for a new audience which are primarily readers?

Jon Jon: I think that initially when we were going through it, the thinking was let’s have the surtitles or the translations at the bottom as a footnote and we thought it would be ok. But for most parts of the book, it started to become very academic. Like “oh let’s read it in Malay first, and then later the second reading of it will be in English”. So eventually we decided to go for after the immediate text–

Nabilah: You did it line by line, right.

Jon Jon: Yeah. And it lent itself a more theatrical feel to it. Because when you watch the plays, some of us would just look at the surtitles. So I thought that was quite a good decision that we came to. In fact if I watch films or I watch plays, if there are subtitles, I would rather read than watch. Because to me, that’s where all the action is. Everything else is interpretation. So I want to give myself that space to interpret.

Nabilah: I like what you said about the hierarchy of languages. If you put everything in the footnotes, it becomes kind of a different experience. Another question for you, sorry, Jon Jon, if you don’t mind. As a playwright, how do you feel seeing your scripts in published form?

Jon Jon: It feels good! I just saw the book today, I touched it today and it’s a different feeling. It’s almost the same feeling I had when my firstborn was born. As a playwright, especially in the local practice, I felt that it's important for this to have been published. Because it’s like when we write and when we have it staged, there’s a sense of collaborative output.

What you see on stage is not necessarily 100% what the playwright wants or the playwright imagines it to be. It’s an interpretation. So what I felt is that with this publication, I would be able to gain a lot more collaborators in terms of getting more people to interpret the issues that I’m trying to raise and interpret the things going on within the play.

So if you guys do get the chance to read the book–I guess that’s why you guys are here right–you will see that I'm very scant with my stage directions. To me that’s like, if I’m going to work with you as a director or as an actor, I want you to give me your interpretation. It shouldn’t be a case for me to tell you how you should act or how you should present this for every second of the play and so on. So yeah, I would love to see your reviews, do tag me on Instagram if you do, I would love to see your interpretations.

Nabilah: It’s quite cool because you call them collaborators. So in this sense the readers would be your collaborators in interpreting your world.

Jon Jon: Yeah for sure.

Nabilah: So, a final question for all three of you, or maybe Jon Jon can elaborate on the previous point: what does this book mean to you personally or for the Singapore theatre scene or the Malay theatre scene?

Irfan: I don’t know whether putting it in that scape is important for playwrights because then we have to define what is Singaporean or what is Malay. Because [Jon Jon and I] talked about publishing together as well. And so I started questioning why publish scripts? It’s just so that other people can read it rather than to look at it as a political or a social thing. I don’t know, is that something?

Jamal: I guess for me also if you guys are in the theatre scene or space, I’m the least visible person. And I don't go to shows, I read shows more than I watch shows. For me to have it crystallized into the book, I feel it helps to establish a written practice rather than all Malay playwrights have to be theatre practitioners in the sense that you have to be a director, or you have to be a set designer. I mean [to Irfan] that's what you do right? But it allows me to be a playwright, and that’s it, I don’t have to be anything else.

Irfan: Yeah, I think you hit it.

Jamal: I’m going to throw in my museum hat here. I think it’s very important for us to document. Not just Malay plays, I think Singaporean plays, by and large. I think there’s been a lot of materials out there that has been performed but have not been documented in an actual book.

I think this project should be ongoing, we should look at publishing more of such materials. Not just because it's good for 20 years down the world, someone can say “oh there’s this person Johnny Jon Jon who wrote this play,” but also because how else can it be interpreted? Maybe internationally, globally perhaps.

Someone somewhere else will pick up a copy of Potong and might want to stage it and have a discussion on some of these sensitive topics. Once upon a time, I think 15 to 20 years ago, some of the topics discussed in either Hawa or Potong won’t happen in a Malay play on a stage where Malay is the primary language. We can’t even talk about homosexuality. And yet somehow Jon Jon, as a cisgender heteronormative male, can talk about these issues and people accept it and it’s okay.

So that’s useful. That’s a useful milestone in Malay theatre and an important milestone in English theatre as well. What happens if it gets picked up by someone in Surabaya, or in Jakarta? Can this contribute to the conversation elsewhere? I think that’s a worthy cause to look at.

Nabilah: I think to add to that as well, it goes beyond the political or trying to politicise this question. For me, I also wrote the foreword. When I was writing the foreword–and I had never written a foreword before–I realise that with Jon Jon, and actually a lot of younger or our generation of theatre makers, no one is contextualising our practice. Or when you Google a show, it’s like reviews, for example. No one is actually trying to see it as what you are trying to do over a long-term time period, you know? Because theatre is too ephemeral and often even if it’s a preview piece, you’re trying to sell the show. It’s not about reading the playwright’s practice. So for me it’s really important to have that contextualised and in a book like this. And there should be more of it.

Jamal: I think after BISIK…?

Irfan: BISIK, yeah. I was just going to say BISIK was such an important book for me as a young maker.

Nabilah: And BISIK is plays by Alfian Sa’at, Noor Effendy Ibrahim and Aidli Mosbit.

Irfan: It was, I think, one of the only collections of Singapore Malay plays that existed. And as a young theatre maker I had never seen any of these plays, and it was very important. So I hope Potong becomes that for another generation. I think it is important to publish, yeah.

Nabilah: I do think it’s very important to publish, even for archival or even for documentation. Also not to need to wait until you’re old to publish as well, I feel that it can be a life practice.

Irfan: But I don’t think you should publish because you want to keep Malay Singaporean plays, you know what I mean? That shouldn’t be the first intention, it will come naturally. It is a secondary after effect.

Nabilah: I don’t know whether it’s appropriate to share here, but we had a conversation about how a playwright isn’t considered a writer in the literary circles until we are published. Or rather that is a belief that is pervasive. So it is pretty interesting that now you are a published writer which somehow has certain currency in the literary scene. I don’t know if you have thoughts about that.

Jon Jon: I agree that the current practice is that if you’re a playwright, until you’re a published playwright, you’re not considered as a literary person. My understanding is that, for example in Malay literature circles, you have to do short stories, you have to do a novel, you have to do poetry and all this stuff in order for you to be considered as a literary person. But I feel that this kind of allows us to lay a stick on the ground for other practitioners who just want to be playwrights, for people who don’t want to be multi-hyphenated, like Irfan. I mean like he’s multi-talented, but not all of us are as hyphenated or talented as he.

Irfan: Aw, thank you. To add to that, I think my reservation to publishing my work is because, Milan Kundera famously said that if you do a certain work in a certain genre, it should not be able to translate into another genre. Like when he writes novels, he makes sure that it cannot become a film. And so you give such importance to the genre. So for me as a playwright, plays are meant to be staged so why publish it? And it’s a demon I’m still battling. But I think hearing Jon Jon say it’s for other people to interpret, I think that’s a really beautiful takeaway from today.

Q&A

Nabilah: What are some things in Potong or Hawa that may not be as apparent to English readers?

Jon Jon: This is quite obvious but people might miss it, the whole idea of conversation, of dialogue, that needs to happen or that is happening within my community.

I think if you don’t come from my community, because other communities might be a little more receptive to the issues I’m raising, and so to you it might just seem like this is normal, this is to be expected. But from a Malay perspective or from a minor [race’s] perspective, these conversations are still quite nascent in the community. For most parts, bringing up all these issues, does put us in a very difficult spot sometimes. When Hawa came out, I had lots of hate mail coming in and mostly from the community itself, you see. So these are the kinds of things that English readers might miss, that this was the context of the writing. I hope that makes sense.

Jamal: I’d like to add, I’m going to go back in history a bit. When we staged Madu Dua in Kuala Lumpur (KL), and I think it was the first restaging in KL. Madu Dua is a play by Alfian Sa’at, and I think the second play was directed by Rohaizad Suaidi.

The issue was that we hadn’t even opened the play yet, it wasn’t even opening night, and there was a picket because some people read the synopsis and they were attacking the play, saying do not question the might and truth of God. Because it’s about a man who had two wives. So the play is about the two wives at home when the man is absent, right, and they’re bantering about why is he late? He’s never late. So it’s about him possibly having a third girl. So the fact that people were against such a thing suggested that they’re not ready for this conversation, even before they watched it.

Fast forward to Jon Jon’s Hawa. We think we’re in a more liberal environment right now, but when we talk about the Malay community, the word “conservative” still comes up every now and then. Actually too often, I think. When we talk about, “oh this is sensitive for the Muslim community, we should censor this, we should not talk about this.” I disagree with that blanket description. I think the community is very diverse in terms of our understanding of faith, our understanding of LGBTQ issues, our opinions on these matters, and I think those conversations should take place, even in the safe environment of a play.

And the voice that Jon Jon has introduced into that conversation is such a unique voice, such a strong voice. Because Jon Jon doesn’t just introduce a situation to you. He pushes you to question that situation. He throws in two characters who are supposedly more religious than the first person, and then he reflects back to you your own hypocrisy. The guy who’s supposed to handle the funeral rites, his bias is revealed. And then this supposedly handsome playboy guy who goes to funerals to pick up chicks, he’s supposed to be religious as well, he’s performing his religious rites, and his bias and bigotry are exposed as well. And I think that’s what he’s showing, he’s reflecting the Malay community back to themselves.

Nabilah: And there’s also that idea of chosen family. So it’s interesting because your characters often are… they’re almost foils to each other? But then I feel like in both Potong and Hawa it kind of moves towards a–I don’t know if ‘ideal’ is the word, but you create a new kind of situation at the end–

Jamal: Is it a compromise?

Nabilah: I don’t think it’s a compromise. I think it’s a beautiful constellation of individuals.

Irfan: I would describe it like the ending of Yasmin Ahmad’s films, where there’s this ideal that exists between characters. It’s this weird space where nothing is wrong.

Jamal: It’s a new space.

Irfan: Yeah, that’s right.

Jon Jon: So basically, Singapore la, right? The ending is always Singapore, right?

Nabilah: Do you write the scenes of your plays in chronological order? What’s your writing process usually like?

Jon Jon: They are never written in chronological order. I will put aside some time, and then Siti comes to me, when I play the music she comes to me and we go through what we need to have written, and then later on I will see how it can be structured together. I already have that overarching plot from the cards, so I just need to know these are the kinds of scenes that can be put into that particular arc and then it will work out. So yeah, I don’t go chronologically.

In terms of process, if you give me a year, I’ll probably write it in three weeks at the end of the year. That’s usually my process. But along the way I will be thinking, speaking to people, to kind of pick up their stories and understand what are the issues that they are faced with. There was a point of time when I wrote throughout the year, but it was always just me writing what I thought would be fantastic, and I realised that nobody likes those kinds of things. I did a play here, and only two people came. And one of them was me! And that was so sad! But I realised it’s my responsibility to write about what others are going through, as opposed to what I think they should be experiencing.

Irfan: Do you ever use tarot cards by chance? For example when you’re stuck, do you just draw randomly?

Jon Jon: Usually I do a three card spread and I do it because I get so nitpicky about names, about like “this guy has to be super perfect.” So I kind of let whatever guide me in a sense, and use the card to say “ok, this is how it should be,” and I will just figure it out along the way.

Irfan: Do you read reversals? I’m kidding.

Jamal: When Siti comes to you, is she in character or is she Siti Siti?

Jon Jon: That’s a difficult question to answer in front of my wife. She comes to me in a shapeless form, I hear her voice and that's it. So I kind of sense that this person has to be a guy, and so that’s how it’s done. So that’s how she comes to me.

But recently, like for Pekung (upcoming play) for example, I want to write a character that is deaf, so now I need Siti K to appear before me in a visual form, otherwise how does she communicate with me?

Nabilah: Telepathically?

Jon Jon: I don’t know if it’s telepathically though, I just feel that… I can hear her talking la. Maybe I should get myself checked in though.

Jamal: Her presence is always benevolent right?

Jon Jon: Yeah obviously it’s benevolent. (Jamal: Just making sure.) I think yesterday Nabilah asked me to what extent do I have her in my mind, right? I told her it’s to the extent that she doesn’t have to apply for a restraining order against me. But yeah, it’s very benevolent and benign.

Nabilah: Thanks for sharing and giving some insight into what might be quite difficult to explain to people about how playwrights conjure up characters and worlds. Often it doesn’t just appear in your head, and you’re not the only person creating it, so it’s quite interesting that you have a Siti K voice telling you certain things as well. Next question: Do your scripts undergo any changes during the devising/rehearsal processes?

Jon Jon: [During] rehearsal, yes, because sometimes people ask me “what does this mean?” Then I’m like, oh yeah it meant so much more when I was writing it and now it doesn’t make sense, so I do minor tweaks.

Otherwise, the only difference–and this was something I had to decide–for Hawa, if you guys watched the first run, there is a scene where Heartbreak Kid’s mom teaches him how to cook fried rice. That’s because when I was in that period of travel, my mom told me that whenever you miss home, that’s what you do: you fry rice, and you can come back home at any point of time. So that was something that I had to decide whether to include in this run or not. Because for Hawa in its second and third run, we didn’t include it because we had no budget to include the fried rice.

Nabilah: Why? Must pay for the rice?

Jon Jon: Must pay for the actors. Because there were two new actors, or two new characters actually. So we had to make that decision, and in the publication I was wondering if I should bring it back. Because that fried rice scene is very personal to me. And as I was sharing with them, there are two things I do when I travel and I do miss home, it’s to either have that fried rice, or to eat KFC, because in KFC the ingredients never change (that’s what they tell us, right?)

Nabilah: Okay um… sorry I got thrown off.

Jon Jon: I’m pretty sure you guys are asking very good questions, and I hope I’m answering them well.

Nabilah: Just now you were talking about the name Hawa, because we were talking about names and all. So Adam is like Adam and Eve, and Hawa is Eve. Was that deliberate?

Jon Jon: No, because Adam (Malay) was like Adam (English) and Adam (English) was Adam (Malay). Because I met people who were returning Singaporeans to serve NS right, and they had names that were, for example, Danial, then some people called him Daniel and some called him Danial. And I thought, poor guy, he can’t even decide for himself. That’s why I chose Adam.

Irfan: It’s one of those names that translates well to English-speaking and Malay-speaking people.

Nabilah: The other day I was in Malaysia and someone spelled Danial as “Denial”. Does Siti K know about how you write your plays?

Jon Jon: I think she knows because I’ve been trying to reach out to her to act in the plays.

Nabilah: And she’s just like “sorry, cannot”?

Jon Jon: Yeah! She managed to agree to one, but unfortunately due to Covid, it was cancelled. But yeah. Like I said, it’s to the extent that I don’t get a restraining order against me.

Irfan: We tried to get her for Potong but you need to book Siti K one year in advance. That’s how busy she is.

Jon Jon: She’s really awesome.

Nabilah: She is awesome. But if she ever says “Sorry, I’m washing my hair that night,” then you’ll know the real reason why she says no to you.

Jon Jon: Why?!

Nabilah: I–Nevermind. Let’s try, you book her one year in advance then you let us know what happens. Do either Jamal or Irfan have a question for Jon Jon?

Irfan: How are you feeling?

Jon Jon: I feel good!

Nabilah: Jon Jon, any last words?

Jon Jon: These two are my last plays.

Jamal: He does this every five years so don’t panic.

Jon Jon: Yeah, just a joke for those of you who are here. If you guys come to watch my future plays, or if we remake the same plays, don’t be shocked if I write in the playwright’s message that this is my last play. Because technically it’s my last play, it’s the play that I last wrote right? I’m sorry I have to leave you guys with a lame joke. (Nabilah: That’s Jon Jon) Yeah, that’s me I guess. I’m really appreciative that Ethos picked up the manuscript.

They actually shared that it’s the first collection of plays that they have published since Alfian’s. I’m really appreciative of everyone who came today for giving us this opportunity to share our thoughts. If you have any questions that you want to ask, feel free to reach out to me, and I hope that we can be collaborators in some way moving forward.

✂️

About the Speakers

Since his first full-length play in 2006, Johnny Jon Jon’s works have evolved from being thought pieces on socio-political constructs to ruminative explorations of the human condition set within the characteristics of a minor literature. Besides the critically acclaimed Hawa (2015) and Potong (2018), his works include National Memory Project (2012), Family Dinner (2017) and Punggah (2020). When not writing plays, Jon Jon writes short stories and facilitates design thinking workshops. He currently lives with his better half as they try to get their startups (children) to become unicorns.

Irfan Kasban is a freelance theatre maker, based in Singapore, who writes, directs, designs, and at times, performs. The former Associate Artistic Director of Teater Ekamatra is responsible for mentoring MEREKA incubation programme, works like CLASSIFIED: Projek Congkak (White Box Festival 2006), Keep Clear (Open Studio, Singapore Arts Festival 2010), Hantaran Buat Mangsa Lupa (M1 Fringe Festival 2012), 94:05 (Kakiseni Festival 2013) and main season shows; This Placement (2012), Tahan (2013), A Beautiful Chance Encounter of a Sewing Machine and an Umbrella on an Operating Table (2014) and ANA (Projek Suitcase 2015). This year he directed several works including, Balance and Duets by Spell#7 (Esplanade’s Fifty) and Three Inches of Alive (TheatreWorks’ Writing & Community 2015). He is currently working on a short film version of his first play Genap 40.

Jamal Mohamad is Senior Manager (Programmes) at National Heritage Board’s Malay Heritage Centre where he develops and implements a variety of activities targeting different audience segments, including underserved communities such as the elderly and youth-at-risk. He was also former Artistic Director of Teater Ekamatra and has background in theatre and film productions. He is a recipient of the Erasmus Mundus Scholarship (2008), Goh Chok Tong Youth Promise Award and National Arts Council Overseas Bursary. Jamal strongly believes that Star Wars and Star Trek fans should really try to get along.

About the Moderator

Nabilah Said is a playwright, editor and poet. Her play ANGKAT (2019) won Best Original Script at the 2020 Life Theatre Awards. She is the founder of playwright collective Main Tulis Group.