"Sometimes these characters use stereotypes... as a way to disarm people" | Potong: Live Reading

Recording of Potong: Live Reading

The live reading of Potong took place at Black Box @ 42 Waterloo Street on 11 June 2022. You can watch the recording above and access the full transcript of the programme on this page. Portions of the transcript have been edited for clarity.

--

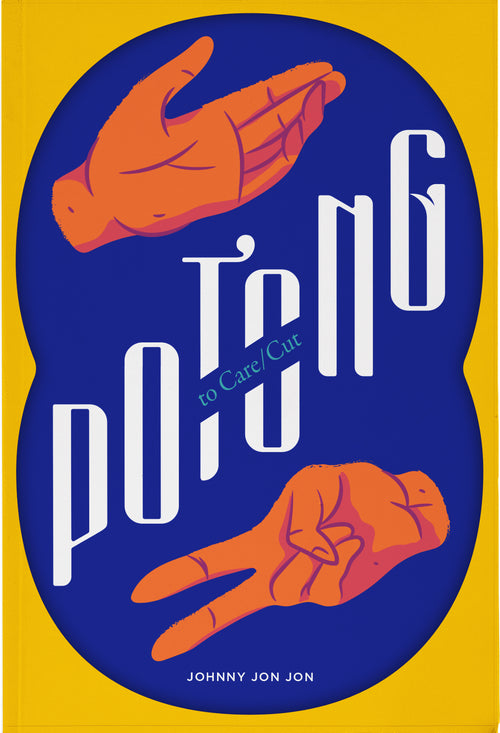

About Potong: To Care/Cut

In Johnny Jon Jon’s plays, seemingly ordinary events are turned into hauntingly profound exchanges when the individual’s sense of self comes under scrutiny.

In Hawa, a new Muslim convert finds herself tasked with overseeing the funeral arrangements of her partner.

In Potong, a son is sent away by a mother to return to Singapore to undergo the coming-of-age rites of passage that await him: circumcision and conscription.

Deftly alternating between beats of humour and tension, Jon Jon reveals how these characters contend with the paradigms, manifest or otherwise, that shape their existence.

--

You can find the speaker bios at the bottom of this page. Enjoy the conversation!

Photo of the post-reading conversation. Left to right: Farah Ong, Munah Bagharib, Irfan Kasban, Nabilah Said (moderator), Johnny Jon Jon, Mohd Fared Jainal, and Salif Hardie

✂

Arin: Hello everyone! I am Arin and I’m the senior editor at Ethos Books. Welcome to the dramatised reading of Potong by Johnny Jon Jon. Before we begin, we would like to thank Centre 42 for partnering with us, and to SingLit Station for supporting this reading. We’d also like to thank Teater Ekamatra for rallying together the crew from the original Potong production to put together this special reading for us. And of course, thank you to all of you here for being here with us.

We’ll be having a 30-minute reading of some scenes from Potong, and we are lucky to have with us the original cast members of the production to read for us today. The reading will be followed by an hour-long conversation and live Q&A with the cast, director and Jon Jon himself.

Now, I’d like to invite Irfan Kasban, the director of the original Potong production who has also directed this special reading for you. He’d like to say a few words to open the reading. Please welcome Irfan.

Irfan: Hello everyone, thank you so much for spending your afternoon with us. Today, we’re gonna do a bite-sized reading of scenes 6, 7 and 8 of Potong. Basically Potong is a story about Adam who is half-Australian, half-Singaporean, who has stayed in Australia for a long time. And he is being ushered back to Singapore for his NS and circumcision. He and his mother who is in Australia, has left him to meet her brother, his uncle, who is cross-dressing as her, with her mother who has alzeimer’s. Scene 6 happens as the first phone call between mother and son. May I invite the actors?

Mono No Aware

“Give up to grace. The ocean takes care of each wave till it gets to shore.”

Adam: Hello?

Siti: Adam! How have you been?

Adam: I’m good. Settling down.

Siti: How’s your uncle?

Adam: Not someone I would have expected.

Siti: Sorry about that.

Adam: It’s ok.

Adam: Mak, did you know that Nenek has Alzheimer’s?

Siti: I do. How is she?

Adam: She’s ok. She’s still chatty. But she doesn’t remember Uncle Saleh.

Siti: Oh you noticed?

Adam: Kind of.

Siti: Comes with the territory.

Adam: It’s quite scary though. Being… forgotten by someone you love.

Siti: Well it’s not like Nenek planned for it.

Adam: I know but still. I wouldn’t want to be forgotten. You wouldn’t forget me right, Mak?

Siti: I love you.

Adam: I love you too, Mak.

Siti: Have you gone for the procedure?

Adam: What procedure?

Siti: Adam…

Adam: Right that procedure. Well… it’s not so easy to arrange.

Siti: Is that so?

Adam: Yeah… the doctor asks a lot of questions. And we might need you to sign off on it. So maybe we just have to wait out.

Siti: How difficult can it be?

Adam: It’s complicated.

Siti: I’m going to get your uncle to help then.

Adam: I think he might not be the right person to help.

Siti: Why not?

Adam: I’m only ok with getting a snip. He… he is more of a chop off the whole thing kind of guy. Siti: Adam, don’t be rude. He’s family.

Adam: Fine… Well you don’t have to worry about the circumcision. I’ll have it figured out.

Siti: Adam…

Adam: Yes, Mak?

Siti: I’m thinking of doing some travelling.

Adam: And this is after you sent me away?

Siti: It’s not like that.

Adam: It’s ok. I get it. Where do you plan on going?

Siti: I haven’t given it much thought yet.

Adam: You’ll be travelling alone?

Siti: I think so. My first solo adventure.

Adam: When do you plan on going?

Siti: I’m not sure as well. That’s the part that makes it exciting right?

Adam: Or scary.

Siti: At most die only.

Adam: What the hell, Mak?

Siti: I’m just kidding.

Adam: You better be.

Adam: Mak, actually, why don’t you just come back to Singapore? I mean… Nenek forgot about Uncle Saleh. I’m pretty sure whatever you did, she has forgotten too. If she can even recognise you at all.

Siti: Haha. And then what, Adam?

Adam: And then you can watch me go through this dumb NS thing and then we can… travel? Siti: You should save that for your girlfriend.

Adam: I don’t have one. And you’re my mother. There’s nothing wrong in wanting to take care of your mother right?

Siti: Alhamdullilah.

Siti: Adam… you must help Uncle Saleh take care of Nenek ok?

Adam: Yes, Mak. But it’s not so easy talking to her.

Siti: Maybe it’s more important that you just listen.

Adam: But I won’t understand a word she says.

Siti: I’m not even sure if at this stage she even understands what comes out of her mouth. But she just needs you to listen.

Adam: I’ll try.

[A fire alarm sounds.]

Adam: What’s that?

Siti: Is that my alarm?

Adam: That sounds like the fire alarm. Did you leave something on the stove?

Siti: What stove?

Adam: Were you cooking?

Siti: Really? Wait let me check… Oh wow there is a fire.

Adam: Put it out!

Siti: I am. I am. Ah shit. What was I cooking? I’ll call you back in a while Adam. I need to clean this mess. Don’t worry I’m fine.

Adam: Are you sure? Call me back when you’re done.

Siti: Mak sayang Adam.

Adam: Adam sayang Mak. Ok go go clean up the mess.

Saleha: What was that about?

Adam: She left the cooking on the stove.

Saleha: She can cook?

Adam: Fried rice, yes.

Saleha: So she’s ok?

Adam: Yeah she managed to put it out.

Adam: Uncle. I’m worried.

Saleha: What’s there to be worried about?

Adam: She’s been acting odd these days.

Saleha: You’re overthinking things.

Adam: Maybe… Wait. Why are you dressed like that?

Saleha: I’m going to pray.

Adam: But you look more like a man now.

Saleha: And you have a problem with that?

Adam: But a moment ago you were…

Saleha: And what difference does it make to you? Does this make me less of an uncle to you? Adam: In any case it makes you more of an uncle to me.

Saleha: Haha. Funny. Anyways, have you prayed?

Adam: No. I was on the phone with Mak.

Saleha: Come. Let’s pray.

Adam: I don’t know how.

Saleha: Come.

Adam: Uncle...

Saleha: Kenapa? Kau datang kotor? (Why? Are you having your menses?)

Adam: I’m sorry?

Saleha: Yes, nephew?

Adam: Have you…?

Down there.

Saleha: You think?

Adam: I don’t know what to think, actually.

Saleha: Come let me show you.

Adam: What the fuck, no!

Saleha: I show you how to pray lah.

Adam: Oh ok.

Scene 7

Yugen

“Within tears, find hidden laughter. Seek treasures amid ruins.”

(Irfan: This scene happens in Dr Dini’s office, the circumcision doctor.)

Dini: So do you have any questions regarding the procedure?

Adam: Question.

Dini: Yes?

Adam: Have you done it?

Dini: I have done it many times. I run this clinic.

Adam: No. As in, have you had it yourself?

Dini: Oh.

Adam: Well?

Dini: Well, it’s none of your business.

Adam: You’re going to do it to me. I think some building of trust is necessary.

Dini: Then let’s do a trust fall.

Adam: Oh come on. You know what I mean.

Dini: You do know I can just say no.

Adam: What happened to the Hippocratic oath?

Dini: Excuse me?

Adam: That you’d treat all patients regardless.

Dini: This procedure is not lifesaving.

Adam: It will make my Mak happy.

Dini: It is not lifesaving.

Adam: Well, it would certainly put my mind at ease.

Dini: You do know that we are anatomically different right? Except of course, I have a pussy, and you are a pussy.

Adam: That’s not appropriate.

Dini: And you asking me if I have had a circumcision is?

Adam: I need to know that you know what you are doing.

Dini: I will have you know that I know what I am doing. What I will be doing. You don’t go to a neurosurgeon and ask if he’s ever had a neurosurgery done, do you?

Adam: But if he has, then I’d know that the procedure is safe. That it’s been done before.

Dini: Oh god. Thank you for the suggestion. Next time I’ll be sure to frame up all the foreskins I’ve snipped.

Adam: That would be grotesque.

Dini: As long as it gives those like you the confidence that I am not some willy-nilly doctor and that I can trim your willy in a nilly if I wanted to. Just like that.

Adam: You are using willy-nilly wrongly.

Dini: Just. Like. That.

[Notices a loose thread on her sleeve and takes out a pair of large tailoring scissors]

Adam: Woah. What’s that for?

Dini: For cutting loose threads.

Adam: That big?

Dini: The right tool for the right job.

Dini: So any more questions?

Adam: So have you?

Dini: Yes.

Adam: Was it like a job requirement?

Dini: No. Maybe. I don’t know. It was done when I was much younger.

Adam: Like my age?

Dini: Like when I was a couple of months old.

Adam: Oh.

Dini: Why? Because you wanted to picture me all of 19 spread-eagled having a part of my genitalia removed?

Adam: No. It’s just… why did you have it so young? I mean, it’s your body, you should be able to decide.

Dini: Like how it is for you, mommy’s boy?

Adam: I can choose not to.

Dini: Yet here you are, obligated. Much obliged.

Adam: Well at least I have a choice. Albeit imaginary.

Dini: Were you immunised?

Adam: Yes of course.

Dini: Did you have a choice?

Adam: No.

Dini: There you go.

Adam: But immunisation is good for me.

Dini: Some might differ.

Adam: Circumcision has no health benefits.

Dini: Some might differ.

Adam: And so what’s your point?

Dini: That when you are young, you trust that your parents have your best interests at heart. Adam: Well not all parents are that virtuous.

Dini: You don’t have a choice.

[A knock. Saleha walks in.]

Adam: Fuck…

Saleha: Hi… sorry. Ini lama lagi tak? (Hi… sorry. Is this going to take any longer?)

Dini: Sorry? Awak siapa eh? (Who are you?)

Saleha: Cik dia. (His uncle.)

Dini: Cik Dia, sorry saya ada patient. (Miss Dia, sorry but I have a patient.)

Saleha: Aku pak cik dia lah. (I am his uncle lah.)

Dini: He’s your uncle?

Adam: He doesn’t look the part, I know.

Saleha: Ini tetek bedek lah sial. (These tits are fake lah fuck.) And you, Adam. You don’t cheebye here. You brought me here.

Adam: Fine.

Saleha: So when can I have the kenduri (Feast where prayers are offered.)?

Adam: What’s that?

Dini: It’s a party.

Saleha: Your coming out party.

Adam: What the hell? It’s a circumcision. Not a castration.

Saleha: Oh? You do that too?

Dini: Oh I don’t do seconds. Happy with just the tips.

Saleha: I am less happy when they come with tips. Haha.

Adam: Can we get back to me?

Dini: As soon as you decide.

Saleha: Decide on?

Dini: He hasn’t decided if he wants to get circumcised.

Saleha: You brought me here but you haven’t decided yet on doing it?

Adam: I needed your support.

Saleha: Do I look like I am your mother?

Adam: Well, you play her well enough.

Dini: I really want to attend to all my appointments today.

Saleha: What appointments?

Dini: The ones waiting outside.

Saleha: Oh… I think they cancelled.

Dini: What do you mean they cancelled?

Saleha: You turn up for your appointment at a clinic for circumcision and you see someone like me in the waiting room, your life starts flashing before your eyes and… you start doubting your decision.

Dini: Bagus.

Adam: I want to do it.

Saleha: Ok great. So when?

Dini: If my reputation hasn’t already gone, we can do it in a month’s time.

Saleha: Jauhnya. (That’s still a long time away.)

Dini: Mudim pun ada musim dia. Ikut school holidays. (We have our seasons too. Usually we follow the schedule of the school holidays.)

Saleha: I see. Adam, when are you enlisting?

Adam: About 4 months away? Enough time for it to heal right?

Dini: As long as you don’t get aroused while recuperating.

Adam: Why would I get aroused? [dini sprays perfume.]

Adam: Oi oi. Don’t do that.

Dini: Just making sure I smell good.

Saleha: Sunat used to be a milestone you know?

Adam: What’s sunat?

Dini: Circumcision.

Saleha: Like that first time you notice a strand of hair growing on your groin and you mistake it for a loose thread and decide to pull at it. It hurts but wah… milestone. But you girl… you make it sound like an experience.

Dini: In my line, we don’t get repeat customers. So I make sure it’s worth their while and something they will remember for the rest of their lives.

Saleha: You’d be surprised how many repeat customers I get…

Adam: Let’s not go there.

Saleha: Am I making you embarrassed, Adam?

Adam: Well, yes.

Saleha: It’s what your mother would have wanted for you.

Dini: That, and this.

Adam: I’m only doing this because she probably knows best what’s good for me. Right?

Saleha: That has always been the case.

Adam: But it wasn’t the same for Nenek and you.

Saleha: Now now, let’s not get personal.

Adam: We are deciding the fate of my foreskin here.

Dini: You know, the foreskin is something you don’t exactly need. It’s really just an extra piece of skin that you can do without physiologically. Like the appendix. But psychologically, it’s a part of you.

Adam: Like how it is for mothers and their children? Forever linked by the psychological umbilical noose.

Saleha: Don’t be dramatic. Your mother went through the full 9 months of pregnancy before she went through 23 hours of labour just to have you. She raised you for the past 18 years not asking for anything of it except for an extra piece of skin that you can do without. Have a thought for her.

Dini: Well, try not to.

Adam: Why?

Dini: It’s a Freud thing.

Adam: Fine fine. I already decided to do it. Banzai.

Saleha: That’s Japanese, you idiot.

Adam: I know that. I just wanted to say “let’s do it”. How do you say that in Malay then?

Saleha: InsyAllah.

Dini: Or jom. Or leggo. Or…

Saleha: InsyaAllah.

Adam: InsyaAllah.

Dini: Amin.

Saleha: You know, after you potong…

Adam: Potong?

Saleha: Cut.

Dini: Snip.

Saleha: As I was saying before you potong me.

Adam: But you said after I potong-ed.

Saleha: I know lah what I said. Susah betul lah bual dengan si orang puteh pantat hitam ni. (It’s so difficult to talk to this Eurasian.)

Dini: What did you want to say?

Saleha: That after he potong, he has to change his name.

Adam: Really? Why?

Saleha: It’s because you’ve become a man.

Dini: Is it?

Saleha: Yes. It’s our family practice. My name before potong was Salehuddin Jamal. After potong Saleh.

Adam: So you truncate it. How about me?

Saleha: Adam Cockburn after potong become A Cock. Or… Dam Cock. Hahahahahha.

Adam: Sial.

Saleha: Bagus, let’s get you started on your Malay. Bahasa tunjuk Bangsa tau? (Language defines a nation.)

Scene 8

Saudade

“Words are a pretext. It is the inner bond that draws one person to another, not words.”

(Irfan: Back at home)

Saleha: Adam. Aku nak keluar. (Adam. I am going out.)

Adam: Oh ok.

Saleha: Ingat kasi Nenek makan ubat. (Remember to give Nenek her medicine.)

Adam: Yes. Lepas TV. (After she’s watched TV.)

Saleha: Lepas makan. (After she’s eaten.)

Adam: Lepas makan apa? (After she’s eaten, what?)

Saleha: Lepas makan apa? (After she’s eaten what?)

Adam: No. Lepas makan ubat and then? (After she’s taken her medication, what then?)

Saleha: Lepas makan ubat, time for Nenek to sleep. (After she’s taken her medication, it’s time for Nenek to sleep.)

Adam: Ok.

Saleha: So lepas makan, makan ubat, lepas tu tidur. (So after she’s eaten, she takes her medication and then she goes to sleep.)

Adam: Ok. Nenek tak payah dinner? (Nenek doesn’t need dinner?)

Saleha: Abeh yang aku masak buat siapa? Tua pek kong? (Then who did I cook for? The deities?)

Adam: Sorry what did you say?

Saleha: Nenek eats her dinner before she eats her medicine.

Adam: Oh I get it now.

Saleha: But ok. It’s been three weeks now and your Malay is getting better. Next week you potong.

Adam: It’s not bad. Mak seems to prefer speaking in Malay as well these days.

Saleha: I see…

Adam: I wasn’t able to get Mak yesterday.

Saleha: Maybe she’s busy. It’s been so long since she’s had time to herself, you know?

Adam: But it’s the first time she hasn’t returned any of my calls.

Saleha: Are you worried?

Adam: I should be. Right?

Saleha: She’s a grown up. Don’t worry. And it’s only been less than a day.

Adam: Maybe I am overthinking things. She did say that she wanted to go on a trip.

Saleha: Exactly. Maybe she went on a road trip across Australia. It’s not like they have reception in the middle of nowhere right?

Adam: Yeah maybe.

Saleha: So no point thinking about it too much. Have you been doing your push-ups?

Adam: Yeah…

Saleha: How many push-ups can you do now?

Adam: 32.

Saleha: 32? Is that your bra size or waistline?

Adam: I still have time. Besides, it’s not like I want to make a career out of it. I’m just going to complete my two years and go back to Perth.

Saleha: But you still have to be prepared.

Adam: And how would you know what it takes to be prepared? By doing push-ups?

Saleha: Then you think by wearing push-up bra is it?

Adam: Itu tetek bedek lah sial. (Those tits are fake lah fuck.)

Saleha: Sial. I might not look it but I was the best in the platoon ok?

Adam: Best dressed?

Saleha: Kepala otak kau. (Your head.)

Adam: They let you serve in the army?

Saleha: Every Singaporean son serves.

Adam: So you actually wanted to serve?

Saleha: Well, there were open showers.

Adam: What?!

Saleha: Cheebye. So judgy.

Adam: You served your National Service just so you could shower naked with other men? Saleha: No lah. I did it because your Nenek wanted me to.

Adam: Really? Even though you were already dressed up by then? [Saleha takes out an old uniform.]

Adam: Is that your old uniform?

Saleha: Sergeant Salehuddin Jamal reporting for duty.

Adam: Nenek must have been proud of you.

Saleha: I’d rather she accept me.

Adam: Sorry.

Saleha: Never mind. I’m going out now. Maybe you can try calling your mother again.

Adam: Yeah. I’m going to do that. Ok you take care, Sergeant.

Saleha: Don’t forget to pray, Recruit. Assalaamualaikum.

Adam: Waalaikumsalaam. [Adam tries calling mak.]

Adam: Come on. Pick up. [Hangs up. Adam tries again. Hangs up. He decides to look at Saleha’s old uniform.]

Nenek: Malam ini kau balik kem, Saleh? (Are you going back to camp, Saleh?)

Adam: Sorry?

Nenek: Yang kau cakap sorry kenapa? (What are you saying sorry for?)

Adam: Malam ini tidur… home. (Tonight I will sleep… at home.)

Nenek: Officer kau tak marah ke? (Your officer won’t be angry?)

Adam: Officer…

Nenek: Lim. Yang kau kata suka marah-marah tu. (Lim. The one that you said loves to scold.)

Adam: Lim…

Nenek: Saleh, Saleh… kau dah nyanyok ke? (Saleh, Saleh… have you gone senile?)

Adam: Mak makan? (Mak eat?)

Nenek: Belum. Tapi Mak dah masak pun. Kau nak makan? (Not yet. But I’ve cooked already. Do you want to eat?)

Adam: Saleh ok.

Nenek: Ok tu nak ke tak nak? (Ok you want to or ok you don’t want to?)

Adam: Saleh makan. (I’ll eat.)

Nenek: Kan macam gini bagus. Macho sikit. Bukan pakai baju perempuan tu semua tu. Macam sundal. Tu dosa kau tau? Mak rasa elok juga kalau kau sign on. Kerja tetap. Tak payah kejarkan pangkat pun. Mak tak kisah pasal tu semua. Mak cuma nak anak mak macam gini. Segak. Handsome. Macho. Tahu? Mari. Kau duduk. Mak pack kan bag kau. Bag kem kau mana? Ah takpe. Mak lipat kan nanti kau tahulah macam mana nak letak dalam bag kau tu. Kau rehat dulu. Nanti lepas ni kita makan samasama. (It’s good to see you like this, more macho and not wearing dresses. Like a whore. It’s sinful, you know? It’s a sin, you know? I think it’s good if you sign on with the Army. A stable job. You don’t even have to chase for rank. I don’t care for all that. I just want my son to be like this. Handsome. Macho. Come, sit here. Let me pack your bags. Where’s your bag for camp? Ah it’s ok. I’ll just fold the clothes and later you can pack them in your bag. Take your rest. After this, we can eat together…)

Chika-chika boom chika-chika boom

Sayang sayang anak ku sayang

Chika-chika boom chika-chika boom

Anak besar rajin belajar

Agar jadi orang berguna

Hidup mewah tidak akan terlantar

Agar jadi orang berguna

Hidup tidak terlantar

Sayang sayang anak ku sayang

Buah hati sayang

(Chika-chika boom chika-chika boom

Loving my beloved child

Chika-chika boom chika-chika boom

Grow up child and study hard

That you can be a useful person

A life of luxury with want for nothing

That you can be a useful person

A life with a want for nothing

Loving my beloved child

Beloved sweetheart)

Adam: Mak…

Nenek: Apa dia Saleh? (What is it, Saleh?)

Adam: Saya sayang Mak. (I love Mak.)

Nenek: Bagus lah tu. Sejuk perut aku dengar. Aku pun sayang kau Saleh. Mak manalah tak sayangkan anak oi. Itu pasal Mak tak mahu kau terikut-ikut sangat nafsu kau tu. Dah. Siap. Jom kita makan. Mana adik kau si Saleha tu tak balik-balik. Asyik merayap aje. Dia tak ingat ke dia tu anak dara sunti. (That’s good to know. I love you too, Saleh. Which mother does not love her child? That is why I don’t want you to give in so much to your urges. Ok, it’s done. Go get ready for dinner. Where has your sister Saleha gone? She’s not back yet. She is always out. Doesn’t she remember that she is a virgin?)

Adam: Saleha keluar. (Saleha went out.)

Nenek: Ye lah aku tahu dia keluar. Tu pasal aku tanya kenapa dia belum balik. (Ya, I know she went out. That’s why I asked why she hasn’t returned yet.)

Nenek: Saleh, Saleh. Kau sajelah yang dengar cakap mak. Jaga hati mak. Tapi jangan pula orang cakap kau mommy’s boy. Takut nanti takde menantu pula aku. (Saleh, Saleh. You are the only one who listens to what I say. You always consider my feelings. But don’t let others call you a mommy’s boy. I want a daughter-in-law still.)

Nenek: Kenapa kau diam? Saleh, Saleh. Ini hah, Hari Raya tak lama lagi. Nanti kawan-kawan army kau datang rumah kan? Kau baik buang tu semua makeup-makeup. Dah dah, mak hidangkan lauk. Makan. (Why are you quiet? Saleh, Saleh. Anyway, Hari Raya is not long away. Your army buddies will come over, right? You better throw away all of your cosmetics. Ok, I am going to serve the dishes. Eat.)

Irfan: Cut!

Arin: Thank you so much to the actors for that wonderful reading! Now we’ll be having the post-reading dialogue and I'd like to pass the time to Nabilah to begin the session. Please join me in welcoming our speakers.

Nabilah: Thank you so much. Perhaps we should end there. So beautiful, right? It’s really awesome to hear what everyone has been up to really, and just to see everyone in the theatre in this black box is quite something to behold. But thank you so much for joining us. Today, you just witnessed a few scenes of Potong by Johnny Jon Jon. But of course today, we are here in conjunction with the publishing of a book - Potong: To Care/Cut, published by Ethos Books, of Jon Jon’s plays. Two of them actually. Hawa and Potong. Today we’ll be talking a lot about Potong, because of the reading and because of course the actors and Irfan being here as well, but later on for the Q&A, feel free to ask about anything, including Jon Jon’s book, his writing, playwriting, even Malay theatre perhaps, because of the people who are here in the room today. I’m gonna start off by maybe giving the actors a bit of a break, after that really awesome reading. Starting with the man himself, Jon Jon.

Yeah Jon Jon, how’re you feeling, having your book out, seeing this reading. What are your thoughts?

Jon Jon: Yeah, I feel good, I mean that’s what I’m supposed to say right. Publishing has been quite a journey for me. I think when I first started, I never thought I’d end up publishing. Because like I said before, I only started theatre because I couldn’t afford film. So to publish is really a milestone. Woah, milestone. I think Ethos has been a really fantastic partner in this journey. Because when I actually approached them, I didn’t see Hawa and Potong being put together into one book. But they could actually see that. In fact, I always thought that Potong needed to exist within a different trilogy. But they saw it as a kind of duality. I shudder to use the word duality because of Suria but ya, they saw it and the way that they put the book together even from the art to helping me with the editing has been fantastic. I think I took too much of the time.

Nabilah: Not at all. This is what everyone is here for. I’ll move on to Irfan - maybe you can tell us why you chose those three scenes that we saw today and what were you kind of hoping for the audience to get from this reading?

Irfan: I chose the three scenes based on, well Jon Jon I wanted to highlight scene 8. The good thing about the play is that scene 6 is where it kind of repeats itself. When the audience can enter into the world without too much exposition. But it’s still exposition.

It’s the last scene, with Adam and his grandmother who thinks he is her son, and that one was, we decided that it was quite emotional, and we wanted to end with grief to enter the dialogue so I hope you all are grieving.

Nabilah: Actually speaking of which, just now when we were doing the rehearsal before this, it felt like there was a bit of emotional responses I felt with the actors coming in, reading it for the first time. So I wanted to ask the actors actually, to embody these roles again, this world again. Anyone can start.

Salif: For me, when I graduated, this was the first play I ever did. So this play is very special to me. As a young actor fresh out of drama school, to have a job already was already like “yeah man! I got a job!” But not only was it that, but it was also that this character was kind of written with me in mind as the main character because of my own personal heritage. You know, me being also Australian-Singaporean, but the big difference is that I grew up here, so I’m Singaporean, but Adam grows up in Australia and he comes back. So you know, for me personally, there’s so much about it that just rings true in my body and my soul and my lived experience even though Adam grows up there and comes back here. The understanding and the feelings are there for me, and of course, with family and grandmother and things like that. All of these live within me every time I read it again. Coming back and just reading it again now still resonates so much with me. It was a very special production for me and I was very grateful to be able to be a part of it. So of course coming back and doing it again, everything is like.. I’m feeling it again.

Nabilah: Thanks Salif. I’m gonna throw it to his mum/Nenek - Farah.

Farah: I don’t know whether I was excited to be reading this again because I think this was one of the more emotionally draining plays that I’ve had to do. But it was fun. So it was also trying to remember how we pitched the piece. I think at that time I was going through that fear of like, man, I’ve reached that stage, main casted as mother and grandmother. That’s it man, I’ve reached that age. But thank god I’m not. I’m not a mother or grandmother at all. But yeah, it was nice revisiting this because this was a lighter version but I did remember that play took me quite a while to snap out of because of what it took out of me and also because I think yeah, you go through that stage where shit, I’m becoming just like my mum, and I think this was also a direct reflection of what most women go through.

Irfan: I just wanted to add that 2018 was a very different time. Most of my casting choices were based on the personality of the person. And I knew Farah was going through a lot with her mum. And there was a lot of resistance during rehearsal to play this mother character. So I think that’s for me where the emotional-ness is. What about you Munah? Fared?

Nabilah: Actually Dr Dini is quite a difficult character I have to say. You have to play a lot of the word play that Jon Jon buries in...he doesn’t even bury, he puts it right there for you. How was it like?

Munah: Reading Jon Jon’s piece; it was beautiful. Because you know exactly what he means without any form of direction and during rehearsals we did talk about that. There was nothing in the script, just words, but that was also the beauty of the script because it was so clear, what he was trying to say. But yeah, I think Potong, with Farah also, it was one of the harder plays for me. Oh I’m going to cry; I’m tired so I’m more emotionally charged ok guys.

It was the year my mum was also diagnosed with dementia, so coming into this show, this play, it was quite difficult for me to read it. There were times in rehearsals where I’m just like, I’m not gonna listen to what’s happening in this scene. But it’s been a few years then, and I think coming back to it, so it was difficult, but in some form of way, it was helping me process what was going on. And then with Dr Dini also, she was kind of the outsider so it’s nice to be able to play a role where I’m sitting on the outside of a family going through someone with dementia, diagnosed with dementia. And then coming back today, it was just like, you know we’ve progressed over the last few years but coming back and reading Potong again, I just recalled all the emotions that came with doing Potong. I mean, that’s art right, it helps you with your life, it helps you heal, so yeah, Potong was very special to me. So that’s all.

Nabilah: That’s for sharing that Munah.

Fared: For Ekamatra, actually when we staged it then in 2018, it was quite a milestone because it was a point of time where we were ready to tackle difficult issues. Being an ethnic minority theatre company, a Malay theatre company, sometimes we ask ourselves, how many Malays do we know out there? So this is one of the pieces where we feel that we need to reach out and it was quite difficult. This personally for me, being this character, because mainly I don’t act as much as some of them. I believe acting is a different ball game and investment to the craft. And this is one piece where I kind of understood the psyche of an actor. What you need to go through. It’s not just coming to rehearsal. For Saleha, the character, I’m thankful to the entire team, my fellow cast, to Irfan, because how do you portray someone who is beyond the facade? It’s a lot of unpacking. Thank you.

Nabilah: Thanks Fared. Sorry i wanted to correct myself. I think all the characters are all very difficult and interesting and marginalised in different ways as well. Maybe I want to throw a question to Jon Jon, which is why did you write this play in the first place? Can you share that? Can you remember what you were responding to?

Jon Jon: I think my most immediate response was also witnessing my grandfather going through dementia. And so every time I visited him with my better half, he would ask me to go get married. I’m like “yes, why not. I’ve already got one, I can go for three.” But otherwise, I could see that sometimes when he doesn’t recognise me, he still tries to make conversation. He wouldn’t recognise my mum, even though my mum was the main caretaker for some time. I thought that if I’m going through that and I felt that maybe out there there’s somebody that’s probably going through this and probably in a much worse way.

For me, I visited only once every month or maybe once every two months. But for others, like the caretakers, I’m sure the trauma must’ve been a lot more. So that was the immediate response. For this part of the story. But for the part about Potong, rather the circumcision part, came to me because I really wanted to be part of the M1 Fringe Fest and the theme for that year was Skin. I was like “skin, why not foreskin” I had this idea where there’d be a foreskin fairy going around collecting all the foreskins, but that didn’t work out I guess. So I’m glad it didn’t. And when I was feeling dejected and rejected, that sense came to me. That hey, maybe there’s more to skin than just the foreskin. Or kin. See what I did there? So yeah.

Nabilah: Jon Jon is all about word play. If you pick up the book you’ll see.

Jon Jon: I’m so sorry.

Nabilah: I guess something I wanted to just bring in, just a small one. Just now Munah was talking about how Jon Jon’s plays doesn’t have a lot of directions. So a lot of it is dialogue or almost all of it, except the section titles and the little lines that accompany each section, so just now you saw it on the screen, so that’s also in the book as per how Jon Jon wrote it. Actually something I realised that was quite interesting, comparing the book with the script that the actors are working off. As someone who works in theatre, the script is very alive. It doesn’t really get script-locked in a way, like film or TV does, I think. An actor, in a live performance, can change it sometimes, depending how you’re responding to your fellow actor and things like that. I don’t know, maybe it’s a question for you first before everyone else. What’s it like having your play preserved in print, but also knowing that it can change and go away from you as a playwright as well. How’s that like?

Jon Jon: oh ya, that’s a good question, so I’m trying to come up with a good answer as well. For me, when I write something, I don’t want to have stage directions, because someone told me once, “are you trying to be a megalomaniac” so I tried to control myself and in my mind, theatre is a collaborative piece. When I pass the script to the director, to the cast, I also treasure and value their input. I don’t want to be too directive. And even when I work with different cast or different directors, my direction to them would be simple. Look, it’s ok if you skip lines. It’s ok if you cut lines as well.

It’s just that every word that I’ve written carries with it meaning. So if you can transfer that meaning into the mood then I’m totally fine with that. I’m not really precious with the words rather, with the idea that I’m trying to push through. For example, when you guys look at the captions right, I’ve always said I don’t need them to be up on the screen. But for Hawa and for Potong, they always have been up on the screen. And some of the audience are like “why do they look like chapter titles”. So to me, really, that’s the best answer I could come up with.

Nabilah: Maybe to respond to that, cos Ethos asked me to write the foreword for the book. I felt that in the section titles and the lines, we see more of you Jon Jon, the writer. Because it’s like the pure version of your ideas which no one can touch through the performance, so maybe that’s why they show it.

Jon Jon: Ya, I guess so.

Nabilah: Cos it’s very specific, you know, you choose like Mono No Aware or Saudade. Certain things you’re trying to go for, or kind of suggest.

Jon Jon: Ya, right. So every title connotes what each scene is supposed to be like. There’s a feel. And to me, that’s it. If the cast understands it, the director understands it, you can remove it. So ya, I’m not very precious about the words, even though I’m very into playing with words. I just leave it to the cast to play with it. Same with the book. For the readers, I let you imagine how you want the setting to be. Because I believe that these stories exist in different pockets of our communities. Yeah, you don’t have to have a very strict vision of Saleh or Saleha. You don’t have to have a strict vision of who Siti or Adam is. And you can see it unfolding in your own communities. That’s how I approached it.

Nabilah: In a previous panel that we did, Jon Jon actually said the reader of the book is a collaborator as well, who completes the world of the play, which I thought was really interesting, from a playwright versus author perspective. Which makes it cool cos theatre is collaborative so you’ve made the reading collaborative as well. Maybe to throw it to the actors. What has been a line that either is your favourite from Potong or a line that you’ve kind of wrestled with or resonates with you a lot? Whether it’s about your character or another character. For Irfan as well.

Farah: It’s the one with Mak’s line. “I’m not even sure if at this stage she even understands what comes out of her mouth. But she just needs you to listen.” I like that line a lot. For obvious reasons I think.

Nabilah: From Mak to Adam. About Nenek.

Fared: My line will be Ini tetek bedek lah sial. But actually my favourite line isn’t mine, it’s a very simple line that says “Mak sayang Adam” and “Adam sayang Mak”. I think it’s being said in the Malay language which makes it even more deeper. Knowing where he’s coming from.

Irfan: I would agree with that. I think in the play, the person is very far away from there. It’s either through a phone call or it’s through somebody else’s body because someone says it to Nenek even though it’s not her son.

Salif: Oh, for this, Ini tetek bedek lah sial. The best, every single night. Never got old.

Munah: I love how you and Fared have the same line, because I have the same line [as Farah]. I did the same thing cos they did warn us and I’ve bookmarked the page and it’s that: “I’m not even sure if at this stage she even understands what comes out of her mouth. But she just needs you to listen.” I think this is something we sometimes forget to do, so it’s a nice reminder.

Nabilah: Duality.

Farah: That’s so real.

Nabilah: Was that your answer as well?

Irfan: Yes. I mean it’s also something that I can’t imagine saying to my mother. Yet it’s a very.. you know what I mean? How do you express love and.. I think that’s how Potong affected me in my readiness to cut off ties. Cos 2018 was when my parents got divorced. So that was.. That was interesting.

Nabilah: So personal. Jon Jon do you have a favourite line?

Jon Jon: My favourite line is this word that repeats. It’s either "silence" or "jedah". Because to me, when things are silent, that’s the noisiest state on stage, and even in conversations. So those are the lines that I really treasure the most. And also my notes when it comes to rehearsals. That silence, you gotta play it. It’s a pregnant pause, it’s not an awkward silence. So I really treasure those.

Nabilah: Is there a reason why you put "jedah" in Malay instead of english in the book?

Jon Jon: Ya cos jedah is heavier. Like... jedah. Silence can be angry. So jedah is one mode. And I really like it. And I picked it up from (Ef)Fendy actually. I never knew the word jedah before I read his work, so when I saw it I was like “that’s some cool shit man”.

Nabilah: Perhaps for the actors right, how do you all feel knowing that this play is in a book published? Like I said, theatre is also very ephemeral. It’s also your names in there, as like this production was presented so-and-so time. How do you feel about that actually? If you have any thoughts about it?

Farah: I’m just happy for Jon Jon actually, more than anything else, that he got published.

Fared: Especially for Ekamatra I think, when we first started working with him. He’s really a special writer and it’s nice that we see his work made into a book format. And can be shared with a larger audience beyond live performance.

Nabilah: Actually me, Irfan and Jon Jon were talking about this during the launch of the book, about there needing to be more published plays by Malay playwrights, and how we don’t have a lot of them. I don’t know Fared, whether you’ve any thoughts about that. Why do you think so, or what do you think is the challenge that needs to be overcome.

Fared: I think you just need to do it la I guess. I do agree, every few years then you have one [published book of plays]. But we have a lot of Malay playwrights. We need to be more proactive to do that. Cos sometimes when you get caught up in the work itself we forget about where this work sits beyond the live environment. Especially since I’m also an educator, so I think it’s very important that generations after that can look at his work again as their reference or their aspiration. Moving forward, I think it’s really about making the effort to make things work.

Nabilah: I guess it’s both archival and documentation but it brings the play... We hope there’s gonna be more restagings of the work, whether it’s in schools or whether it’s Ekamatra, and of Hawa as well, both Hawa and Potong. I think that’s why plays are also published in books as well. Increasing access. Cos I think Ekamatra is trying to do more of that as well, archive and documentation. I’m doing PR for Ekamatra. I think we’ve gotten some questions from the audience. Very cute questions actually, I think there’s some students in the theatre, cos they call you Mr Jon.

Jon Jon: Hello.

Nabilah: Dear Mr Jon, how long, on and off did it take you to write Potong?

Jon Jon: They always give me a year to write something from conceptualisation. I usually take about three weeks to write a whole play. I usually need to kind of bake the story a bit. And then meet people, look at things. Then let the thing synthesise and crystallise during the last month. So usually about three weeks.

Nabilah: So short.

Jon Jon: Ya, it is short. But it works, cos I write better under pressure. To be clear, it’s three weeks ideally before rehearsal starts. I won't try to change the script one week before the show. I don’t think that I’m that kind of person.

Nabilah: Follow up - Dear Mr Jon, is the play autobiographical? Based on your own personal experience? I mean, beyond what you’ve shared just now.

Jon Jon: I guess some things are, if you can say it as such. That’s a very painful question actually. I think in some ways they are, Potong and Hawa. I was trying to revisit those past experiences and either make right or come to terms with them through the writing but I’ve always felt that, it should never be about me or what I think the situation is. Cos I remember I keeping sharing this with Nabilah and Ethos. Having this thing done here in C42 is really amazing cos the last time I wrote something that I felt was autobiographical, I think only two people came and it was staged here in C42. And I’ve always realised that a bit of it comes from my background, my experiences, but it should speak for others, in a sense. Others who are marginalised, who do not have the voice or the platform, that kind of thing.

Nabilah: Thanks for sharing that. I’ll move the attention away from you. To Irfan - Dear Irfan, you said you used to cast according to person/personality and how it goes with the character. How does it differ now? And does it shift how you feel theatre?

Irfan: I worked with everyone in different capacities before we did Potong and I thought woah it’s the perfect time to get all of them together. Interestingly enough, after Potong, I didn’t tell you guys this, but I felt really bad, because I didn’t know how to get you all out of it. I felt that there was no safety guiding you, ushering you out of the work. Cos you know how theatre is in Singapore, you rush to the next one. So what I did was I tried becoming an actor myself and that is one of the most painful experiences ever. It’s really hard when you have to embody this character for a few nights and go through the highs and lows and are left without guidance. So I apologise if I have at any point been, not safe.

Nabilah: But I think this question of safety came about kind of within the last few years, so it could have been the early times when we didn’t really think about safety that much, especially in Malay theatre.

Irfan: I mean, for example, there’s a letter that Mak writes to Adam, and Dr Dini reads it out. And I asked Munah if she would be ok to have her mother write it in her own handwriting. So it affects you. I don’t know. Sometimes it’s tricky, because I do want to chase after that pure… and I don’t see the character and the actor different. I think when I talk about ritual performance. The first person it should affect is the actor. And then the audience can follow.

Nabilah: I wonder if the actors have anything to respond.

Farah: Disclaimer, I’m not Nenek. I’m no Nenek, yet.

Munah: Yes, Farah has made it. Yeah, yes, but I thought, I agreed to it. I don’t know. Thank you for thinking of that, but I feel like Irfan also had a conversation with me to see whether I was ok with it and it was all very personal things. I think he knew my story and he knew exactly what I was going through. It was nice and I did tell my mum like “oh you’re gonna be part of the show.” and she did come to watch and she loves that she wrote that letter that I read. So I thought that was quite fun. And she always likes everything that I do, everything is like “great”. It’s nice for her to be part of it, part of something that I’ve been doing.

Irfan: It looks like I’m favouring Munah but no. This is everyone as well. Everyone also. I think with Fared, there was a lot of duality. This play was presented as Theater Ekamatra’s 30th anniversary. There was Fared as the artistic director and Fared as this beautiful actor who I worked with in ‘94 or ‘95. And we talked a lot about Peter Pan. Remember Peter Pan?

Nabilah: Which Peter Pan? The band or...?

Irfan: [turns to Fared] Are you okay with me sharing? Ok so Fared has this like Peter Pan syndrome where he doesn’t want to grow up. And I thought Saleha was interesting in that she plays different roles and at different times, and always suppressing her true self, so that was something that I wanted to bring out from Fared during Potong. Why do I wanna cry, it’s so stupid.

Nabilah: To bring it back to Jon Jon. I think it’s also how the play… there’s so many themes there, and I think sometimes we make a lot of the wordplay. But sometimes it comes at the expense of like… no actually it’s so beautiful beyond that funny wordplay. Oh my god he went there but he really goes there because of themes. There’s a lot of themes - gender, sexuality, family, sacrifice - even the idea of circumcision. I remember reading a review where someone was like saying how—because the books come with translations; there’s a lot of footnotes and translations—someone said like oh but it’s very hard to translate the significance of certain rituals and certain cultural things that we do in Malay society or families unless you’re in it. And maybe that’s why we feel it, because a lot of us, we come from Malay families la. However mixed they are. I don’t know, how do you feel that people are feeling so much?

Jon Jon: I feel bad. I always feel like, every time—cos I usually watch the plays—people suddenly start crying next to me. And I’m so sorry right. And then sometimes we get actors like hey, this really helped me to go through some painful stuff I was going through. I feel better because I feel like I’ve helped somebody, but I still feel bad getting the person to revisit some past trauma. So in general I feel bad. But hey, you cannot spell funeral without fun right?

Farah: This was in Hawa right?

Jon Jon: It was in Hawa, yeah. I don’t know whether you guys know the back story of that line. There was this Australian dude who came to my aunt’s funeral and he started recording everything on his handy camcorder. The entire thing. And then at the end of the day, he gives us the recording. When he was recording, everybody felt like “my god, what is this guy doing? How weird is this mat salleh?”. But then when we rewatched it, it felt different. It helped us to process the loss. Cos sometimes, when you are at the cemetery, you're kind of like “oh I have to go through this process, I have to make sure it’s done this way and that way.” but when you watch it again through a different format it helps you to process it better. But now, it’s normal. Cos during Covid with all the burials, everyone was livestreaming the funeral. Which was kind of weird in a way? I was at my grandfather’s funeral. We were livestreaming to family members all the way in Malacca you know. And I thought it was funny. I mean, I wasn’t laughing when I was there, but I thought it was funny how certain things have changed over such a short period of time.

Irfan: Going back to the question, the line of exploiting and transforming is very thin. So how do I navigate that, and especially with Jon Jon’s text as well.

Nabilah: To explain what I was saying earlier. I feel like everyone has that uncle or that cousin who maybe you know is transgender, or crossdressing. And I feel like that identity is not... we don’t talk about it enough, and that’s why when we see it, it sometimes becomes, I feel like sometimes it comes off as funny as a first reaction, but there’s so much depth and that’s why a character like Saleha is very important to see in theatre.

Irfan: Can I add to that? During rehearsals, we also had a lot of talk about how to not make Saleha, the character of Saleha, be a stereotype. Sometimes these characters use the stereotypes to their advantage; they use it as a way to disarm people. And then that’s where we found power in Saleha. She’s very sharp and she acknowledges her fate. But within that human, within that wit, there’s a lot of hurt that lies beneath. So it is okay sometimes to play cliches.

Salif: Can I say just one last thing? Just to jump in on this whole thing about you know the casting and stuff like that. I think it’s very unique and quite a special thing in Singapore because you know we are so small right. So it’s actually this idea of kampung you know. And Irfan talks about how he feels bad because you know we all have our own thing and he kind of tapped in on that, but it’s nice in a way to be able to. Especially me coming from you know cos, I’m of both-ish cultures but I grew up here so I’ve always felt Malay but you know how people can be growing up like “ah ni mat salleh”. I’ve never really felt like I belong. But when I came in, when I was cast with the Malay theatre company, you know, it was very big for me. It was a really amazing opportunity and experience and it really... I was so grateful for it.

So to come in and actually you know. It’s the same [for me as the character], I have a single mum. He has a single mum. My grandmother doesn’t have dementia but you know there’s a strained-ish relationship there. So for me to be able to share that with a little kampung, with this special group of people, this small community, to be able to have that safe space with one another, and to be able to really share, I think it’s quite unique, and it’s quite special.

And you know moving forward of course in terms of casting you don’t want to do that, you know I think casting should be something that is open. Anyone should be able to… as an actor I should be able to audition for any role. I think that maybe doesn’t happen so much in Singapore. I feel like we need to move forward with that. A lot of theatre companies are quite safe in that they like to use.. I mean anyone who watches theatre in Singapore would know this. You tend to see the same people again and again and again so I think we should move away from there but at the same time I think there is something to be said about the safety.

Nabilah: Thanks for that Salif. I do agree that we should have more open auditions, especially because there’s young people in this theatre. I also think it helps in terms of bringing theatre forward, you know, rather than always seeing the same faces over and over again. Yes okay, I’m gonna go back to the Q&A. Dear Jon, what would it be like if you directed your own plays?

Jon Jon: It’d be so boring.

Nabilah: Why?

Jon Jon: You get tired of going through what I have in my mind. But also in terms of casting, you won’t get so diverse of a cast. I’ll just cast Siti K(halijah) for all the roles because she is the prototype for all the characters and I always start writing with her speaking to me the lines. So if I was the director, being so simple-minded, I’d be just like, ya, Siti K for every role. That would be a boring play.

Irfan: Ya we knew. Siti K was busy.

Jon Jon: Actually for every play, it’s always the same. All the actors are told like “Siti K is supposed to be you. Live with that”.

Nabilah: Not a question but “Please restage. Sold out” this person couldn’t go because it was sold out. Okay, to all, this question’s very funny so I’m gonna read it. “Which paragraph do you think would you hope to see as an excerpt in an O level paper.”

Farah: Ini tetek bedek lah sial. That would work though. Right?

Nabilah: Gender relations..

Farah: Translating... Can’t find an English term for it.

Irfan: There’s urgency as well. This one! This one!

Nabilah: Dear Jon, how do you divorce yourself from your works? How do you do your research such that it affects others who are marginalised?

Jon Jon: Ah yeah so Nabilah actually covers this really well in her foreword. The beauty of it is that I’m Jon Jon right, but outside people don’t really know me as Jon Jon. I go by my given name. So it’s easier for me to slip in and out of conversations, and it helps me to like filter certain thinking. Yeah, like hey this is me as Jon Jon, I’m trying to get stuff in to do my writing. And this is me as you-won’t-know-my-name, focusing on professional stuff. That’s how I filter. And I’ve been fortunate cos in my career, or in my life, I’ve met so many different people, of different backgrounds, of different interests. That really helps me pick up stories. And I guess the other thing I like to do is to just spend more time listening to people. Cos at the root of it, even when people complain about stuff, actually there’s always an underlying issue they’re trying to speak up about. And so that helps me.

Nabilah: I think the other part of the question is also like, how do you make sure that, cos, you’re male for example. So how do you tell stories that’s like not about you per se?

Jon Jon: Ya I get this a lot. Hey why you write about members of the LGBTQ? You’re not one of them right? And I’m like, they’re human right? Like, they have feelings too right? Like, they deserve to... everybody deserves to be loved right? Ya so for me, when I get those kind of questions, I get very triggered. Because for me, I don’t see people by what others define them. I accept people for who they are, how they choose to present themselves. And that to me is enough. Because at the end of the day, I also would want acceptance from others.

And at the end of the day, I said it in my play, even God waits till the end of time to judge us, so I don’t see why we have to go into that space. And so for me, when I speak to people from different communities, people from different fringes, in my mind I just want to understand how are you as a human processing this experience. And I hope that I’ll be able to bring it out onto centre-stage, to help others process and also gain some awareness. And that’s the thing about all the jokes that I put inside. I always want to feel that, as you laugh, you wonder "what am I laughing about actually? Am I laughing about the situation that others are in? Is it a case of"... What’s that german word?

Nabilah: Schadenfreude?

Jon Jon: Ya that word ya. Where it seems like you’re laughing at other people’s expense, or are you part of that system that puts them out on the fringe?

Nabilah: Thanks for that. Someone asked what do you write plays for?

Jon Jon: Money?

Nabilah: Really?

Jon Jon: No lah. What do I write plays for? It’s fun. Gets annoying but it doesn’t get annoying. I just write cos I know that it’s just stories that I need to tell, so I take some time to write in between whatever work that I’m doing.

Nabilah: Here’s a question for everyone on the panel. Someone asked “considering the closeness of practitioners in Malay theatre, what advice do you have for complete beginners?”

Farah: Change profession. Don’t get into it. I’m kidding.

Nabilah: I mean because from the outside, it feels like everyone knows everyone. So for a complete beginner, what advice would you give?

Salif: Can I say something? As an actor in Singapore, you have to understand the context. As an actor anywhere, you know if you’re an actor in the big wide world, in the UK [for example], you gotta understand the market and the environment that you’re in. In Singapore, you’ve to understand if it’s small, a nice little community, then how do you get into that community, how do you understand that community? You have to be a part of that community. We don’t exist in a vacuum. As an actor trying to come into the community to be a part of it, you have to get to know the people. You have to be okay with letting them see you in your different capabilities, letting them see you fail. Whatever it is, try. You have to try.

I would really want to say that, going back to what I said just now, we have to start looking at a small community as a really good thing. Because we’re so small, and because everyone knows everyone. In that way, if you go out, try your best, and are really honest, people see that, that goes around. It’s very fast. You know, similarly, if you are not, then people know also la. But in that way, we should really feel happy about that, because to be able to get that opportunity and that space to grow, as an actor, in that safe community where people know okay, this guy, girl, whatever, working hard, wants to be an actor, actress, you know, is brave every single time.

And for people to support you in that way, it’s nice; it’s a wonderful thing. We’re not out in the world where someone is just gonna take advantage of you because we’re so small. Everyone knows everyone. So really lean into that, I would say. Because if your dream is to be an actor, to start here, and to start in a small community where everyone knows everyone and you have that safety net, it’s nice, it’s very good. So for me when I started, to have Irfan want to really tap into my own experiences as Salif, and to know that whatever it was I knew that the people I was working with in this production, you know the intention was for the work. The intention was here, it would stay here. And that’s what happened you know. So as an actor, as a human being, you get to grow. If you have the right people around you, you will feel like you can be brave enough. But I would say, you know, lean into that. Don’t be afraid of it.

Munah: Yeah just to add to that, I think I understand the struggle or the “dunno where to go as a new actor”. When I first started out, I wanted so much to be in theatre, but it was a community that you had to, like “how do I get into them” or “how do I get them to know me” so I felt that I had no idea too, but if that’s really what you want to do, then like what Salif said, you gotta meet people, go for shows, if it’s just talking about my experience, go for courses, find out about workshops and things like that, you gotta put yourself out there. Try and learn. I didn’t go to art school, but I had to find ways to do this or know enough, and you’re bound to meet someone when you go for these workshops that people run; Ekamatra would sometimes run courses and stuff as well. So go for that, make sure that people know you, and make it known that this is what you want to do. And that’s how you first get your step in.

Salif: Email, anything, you know. Because it's so small, you just google, okay Ekamatra, who is who, then just email. It’s done.

Irfan: And doing all the small little things like being crew. I learnt so much about theatre by being a crew for a month plus for Wild Rice. I was under Elnie under the campaign to confer Jamie J, and I watched actors every night performing and I saw how Ivan worked. You might think “uh, this is not the way to be an actor” but there is something about observing as well. Observing is very important. Be an FOH (front of house). They will let you watch the show if there’s a seat. Do all these things if you really want to do it. You cannot let your ego of wanting to be an actor stop you from becoming more than what you imagine yourself to be. Workshops are really important.

Farah: It’s also to start somewhere. I agree. It’s just to put yourself out there or how else would you put it right? And I also believe that you have to do the things that you have to do in order for you to do the things that you want to do. So sometimes like, I started out at Theatre Kami. It was from a Salina play. A book that was an A Levels text. Which I read and I was 15 or 14 right and I was too young to go and watch plays. My brother brought back the programme. And then I read every single page. They were looking for youth volunteers and that’s how I started. I started doing lighting, costume, you know it, and then I hung around just to be able to watch other rehearsals and just, make yourself really thick-skinned and offer yourself a bit more coffee and like “oh, because I wanna watch rehearsals” and you just got to start.

I think it’s harder now, to be fair, I think it’s harder now, because there is a ready market. There are art schools, and not every parent can afford to send their kids to an art school right? So workshops are also important. And because there’s a ready market, there’s a ready stream of people with certain qualifications and certain things and therefore people who are not within that reach will find it harder. Then I think the workshops are really good as well. And basically just to start somewhere, you can’t be idealistic. You’ve got to start somewhere, and just do it. Front of house, anywhere. Right?

Irfan: And go for auditions, just go. It’s scary, it sucks to go for an audition, and you know what, be okay with rejection.

Farah: It still sucks to audition, even at my age, it still sucks to audition. We all still, you know deep down, we hate it. But it’s a necessary evil. So yeah, you gotta do it.

Fared: Just to add a bit. You must understand that theatre is a space where you will be exposed of your vulnerabilities and there’ll be times where you’ll feel insecure and all these very negative things but I do believe that not just here in Ekamatra, but everywhere else—theatre companies and the people that you work with—there’s enough tender love and care that will support you. So don’t be afraid to give. Okay? On your part as long as you are giving, on the other side, whichever companies you work with or whoever you work with, they will be supporting you.

Nabilah: Thank you so much for that advice. I also wanted to bring it back to playwriting and writing as well, cos speaking of being insecure, I think the playwright is sometimes the most insecure because, I mean I don’t know about Jon Jon, but I feel that sometimes it can be very lonely, right. When you’re writing it, it’s before the actors come in, before the directors comes in usually. How’s that like? And also someone asked, how did you break into the local theatre scene as well?

Jon Jon: I’m not insecure. I’m just awkward so… how I got started right, I was quite lucky because I got asked to write a play for school, and then, teachers couldn’t find any other student to write a play, and then, it just kept on happening. And then I got into Ekamatra, and they said "hey, this guy can write. Not sure whether he’s good, but he can write. So let’s put him on the programme, or something". And so things just kept snowballing. And eventually in University, I realised that there’s a cheat code to your FYP (final year project). If you choose to write a play in Malay, your Australian teacher or your Australian professor cannot judge you. He can’t say that it’s wrong, right. This might work.

Hawa was an FYP project actually. I felt bad for my professor cos she was like, "ya this is good". So that’s how I got started, but like what they said, it’s really about putting your work out there. Like, it’s okay. For the writer yourself, you must be very very clear that you’re not writing for yourself. It’s never a case where you’re trying to tell people about your vision for the world. That’s what I feel, it really should be about the people. And that’s why for me, it’s really important for me to situate myself within that minor literature. Because for me it’s really about pulling out stories from the minorities, from the fringes into the main stage. It’s not about putting my fantastical imagination out on stage, because it just doesn’t work. You have to understand that your work has to be kind of commercial in a sense? And it’s not gonna be commercial if it’s just gonna be like the mental masturbations of yourself. You have to relate to people.

And I think on a more macro level, from a business perspective (me being a business strategy associate also), you have to create demand, if you want to be part of this industry. As a starter, how you create demand is to get more people to come watch shows as you go out and observe and study the industry. If you don’t create that initial demand, by the time you get in, there’s not gonna be a demand, and there will be less companies, less plays being staged and so on. So the first step to being successful within the industry, is to generate demand yourself first. It’s a chicken or egg thing, right?

Nabilah: Thanks for that. I wanna give you the last word so think about it, but there’s a question that we can’t even get into but I think we also did talk about it which is why this play should be published. We talked a little bit about that but I think this is basically why we need any play to be written or staged or performed or published. To me, they’re all part of a larger thing that we’re trying to do, you know. It’s not just about the publishing, it’s everything actually. This discussion, this room that we’re in, this moment that we’re all in, whatever we’re all thinking about individually, collectively. And I think that’s why we do what we do. Your last word.

Jon Jon: Wow, ok, be awkward, brave and kind. I think that’s the last words I want to give. Because it’s okay to kind of be uncomfortable in some situations, as long as you’re very clear that you’re trying to learn something out of that experience. It’s always important to be brave about certain things. Because sometimes you’re going to face the loss of breakbares and shit. Like when Hawa came out, I got hate mail coming in to say like, "hey, you’re muslim right, why are you writing about this". So, if you really believe in certain things, you really have to go through it.

And finally, be kind. Even to the person on the opposite side who hates your guts for doing whatever it is that you did. It’s important to understand that no one wakes up in the morning wanting to screw up, or wanting to get into bad mistakes or whatsoever right. Nobody says, good morning, I’m gonna screw up today. So, you gotta be compassionate enough, and be kind to say, maybe if the person is spewing so much hate, it’s only because of a certain thing that happened to him before, so I need to have a conversation with him. Not a debate, but a conversation. So always make sure that you’re awkward, brave and kind.

Nabilah: Thank you so much for that. Thank you so much for the discussion as well, actors and Irfan and all.

✂

About the Speakers

Farah Ong is an independent artist based and residing in Singapore. She is an actor, a performance artist, a voiceover artist and a teaching artist. She makes art, sometimes in the most unconventional medium and forms. Farah is most alive when performing. She finds the human connection pleasurable when teaching. She tries to understand pain when creating performances. Currently she is going through a period of finding joy in everything but Art. Perhaps she is trying to figure out what it means to be human. And she believes that if we look at this world through the eyes of a child, there would be magic in everything. Farah possesses the curiosity of a 5 year old, and she’s always a child at heart.

Through writing, directing, performing, and designing, Irfan Kasban hopes to create intricate universes as a celebration of space and time. A freelance professional since 2006, he was an Associate Artist with Teater Ekamatra for 10 years, and had a one-year associateship with The Theatre Practice in 2019. In 2020, Irfan was conferred the Young Artist Award by the National Arts Council.

Since his first full-length play in 2006, Johnny Jon Jon’s works have evolved from being thought pieces on socio-political constructs to ruminative explorations of the human condition set within the characteristics of a minor literature. Besides the critically acclaimed Hawa and Potong , his works include National Memory Project, Family Dinner and Punggah. When not writing plays, Jon Jon writes short stories and facilitates design thinking workshops. He currently lives with his better half as they try to get their startups (aka children) to become unicorns.

Mohd Fared Jainal engages in cross-disciplinary work that delves into the realms of both visual and performing arts, with a particular interest in space, body and design. A strong advocate of physical theatre, he is constantly exploring body craft in performance. He is also studying the relationships between elements and principles of art and the human self, asserting these links to be in symmetry and simultaneously manipulative. Fared is the artistic director of Ekamatra and also teaches at School of the Arts (SOTA).

Munah Bagharib entered the entertainment business as a television actress and one half of YouTube duo, MunahHirzi, a channel in which she co-hosted satirical videos on social and political topics. She has gone on to become a prolific actress on both television and stage, with her recent film debut in Tiong Bahru Social Club (2020), and more recently her theatre performance as Maria Menado on Lost Cinema 20/20 (2021) where she was nominated Best Actress in The Straits Times Life! Theatre Awards 2020.

Salif Hardie is a Singaporean Actor of Malay and Australian descent. He received his training at Lasalle College of the Arts, graduating in 2017. Currently helming the role of Hafiq Ibrahim on Channel 5's Sunny Side Up, he also actively seeks to still be a part of the theatre scene- most recently seen on stage as Jim the Gentleman Caller in Pangdemonium's production of The Glass Menagerie.

About the Moderator

Nabilah Said is a playwright, editor and artist who works with text as material across different forms. She has worked with Teater Ekamatra, The Necessary Stage and T>:Works, and her play ANGKAT won Best Original Script at the Life Theatre Awards 2019.